Jean Seberg, the Iowan farm girl who became a Parisian modernist, has been given the biopic treatment. JAMES OLIVER looks back at the tragic life of a talented, tortured star.

It’s probably lazy to describe Jean Seberg as ‘an icon’, but it’s no less true for that. Her turn in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless made her one of the most famous faces in cinema, her image reproduced innumerable times in the innumerable articles about that legendary movie. But calling her an ‘icon’ diminishes the person behind the image.

There was much more to Jean Seberg than a cool photo – enough, in fact, to justify a new biopic all about her. Unimaginatively entitled Seberg, it stars Kristen Stewart as the actress in her middle years and suggests she was not so much an ‘icon’ as martyr, a victim of angry, powerful men. And tragically, although the film employs a certain dramatic license, that’s basically how her life went down.

She was born (in 1938) in Iowa and might have stayed there had destiny not intervened: the papers were full of talk of a Hollywood big-wig scouring the country looking for an unknown to star in his next picture. If it was up to Jean, she probably wouldn’t have bothered applying but others encouraged her: she acted in school and was good at it. So she gave it a go. And whaddya know? She got the part.

The purpose of this Eisenhower-era X Factor was to find the lead for a film called Saint Joan, adapted from George Bernard Shaw’s play about Joan of Arc. Seberg beat 3,000 other hopefuls to get the part, earning predictable headlines about fairy tales.

Only, what the 18-year-old Jean Seberg was about to discover was that it was the sort of fairy tale with an ogre. Those who knew him socially said Otto Preminger, producer and director of Saint Joan, was a lovely man, charming and witty. Those who worked with him told a different story: when he was at work, Preminger was unquestionably one of the biggest bastards to ever bestride a soundstage.

His treatment of Seberg was especially harsh. It was bad enough that an untrained teenage newcomer found herself acting opposite the likes of John Gielgud and Anton Walbrook but she had to do it in the face of Hurricane Otto giving her the full hairdryer treatment on a daily – hourly! – basis. And if that wasn’t enough, she very nearly suffered the same fate as the person she was playing: while filming Joan’s fiery execution, a special effect went wrong and Seberg was badly burned.

All that – and for what? “I have two memories of Saint Joan,” she remembered in 1961, four years after the film’s release. “The first was being burned at the stake in the picture. The second was being burned at the stake by the critics. The latter hurt more.” But sloping off back to Iowa wasn’t an option – she’d signed a seven-year contract with Preminger, and had to go into the ring with him all over again for Bonjour Tristesse.

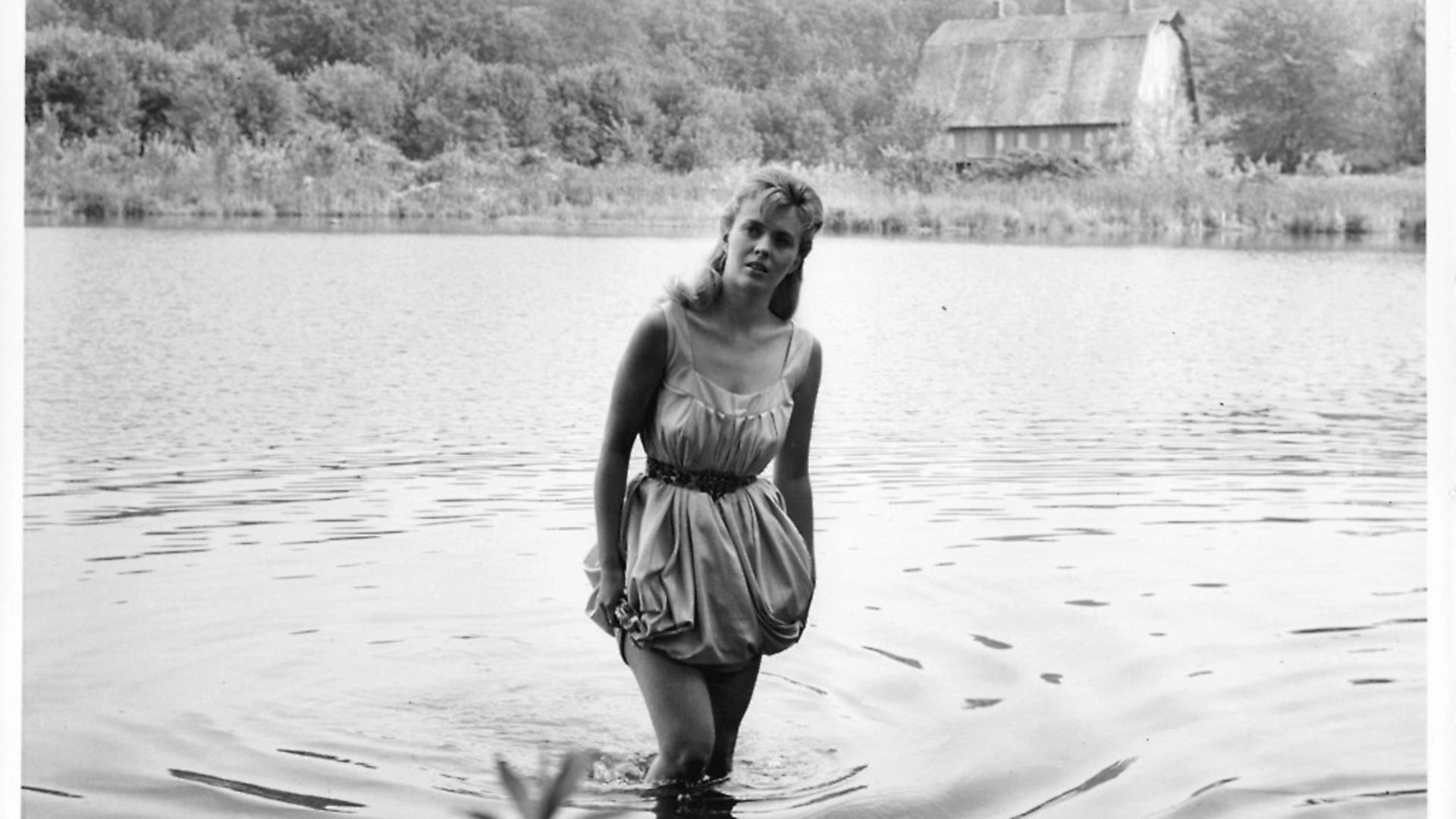

This was a significantly better film, not least because of Seberg as the capricious young heroine. She was more confident now, better able to stand her ground. The experience was especially happy as it took her to France. Not only had Saint Joan been more warmly received there than in the US, Seberg, herself had been hailed as a style icon – the pixie crop Preminger forced upon her to play the Maid of Orleans was swiftly adopted by more fashionable Parisiennes.

After Saint Joan, Hollywood wasn’t much interested in Seberg but, again, the French were more forthcoming.

When Jean-Luc Godard was planning the film that would take him from polemical critic to polemical filmmaker, he sought out Seberg to take one of the leading roles: Preminger’s press machine had made her a celebrity, after all. Better yet, the box-office failures of her first films meant she was cheap.

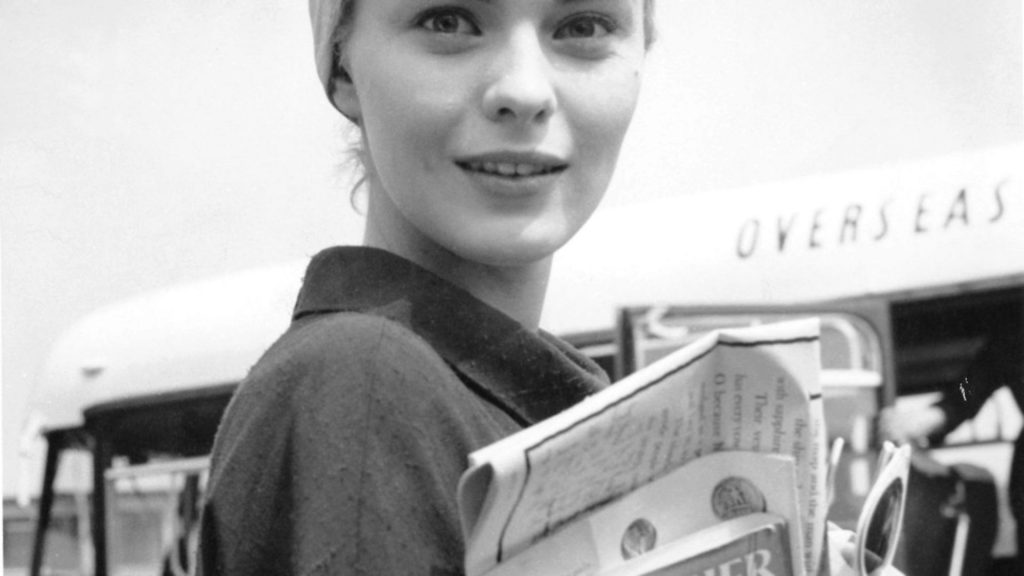

Breathless (À bout de souffle) established one of the faces of the French nouvelle vague. True, she gave better performances in other films but there’s a vivaciousness here that remains compelling. We first meet her selling the International Herald Tribune on the Champs-Élysées; it’s an unpolished moment and all the more powerful for that, a demonstration of a new freedom in movies that remains intoxicating 60 years on.

Breathless revived her career in America; she appeared, notably, as a psychiatric patient in Lilith opposite Warren Beatty. Rather less notably, she showed up in the cowboy musical Paint Your Wagon, wherein her character sets up a ménage à trois with Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood. By 1969, she was famous enough to take third billing behind Burt Lancaster and Dean Martin on the disaster movie Airport. She didn’t realise it then, but that film would begin the next stage of her life.

Seberg had always cared passionately about equality. Aged 14, and still living in white-bread Iowa, she joined the NAACP (National Association for the Advance of Colored People, the venerable American anti-racism organisation) and was a dedicated supporter of the civil rights movement, including financially. So it was only natural for her to donate $10,500 of her generous Airport salary to another cause she believed in: the Black Panthers.

The Panthers were then a new front in the battle for racial equality in the USA, one that gained prominence after the assassination of Martin Luther King. They were (and are) routinely described as ‘militants’, but that is to elide the community work that was their core mission: Seberg intended her donation to fund the breakfast programmes they established to feed hungry children. But not everyone was impressed by her charity.

Her endowment caught the eye of J. Edgar Hoover, superannuated head of the FBI, the organisation he’d founded and ran according to his own prejudices. As might be expected of a man who thought Dr. King was an “extremist”, Hoover was terrified by the Panthers, who didn’t even have King’s commitment to non-violence.

His head filled with apocalyptic visions of race wars and worse, Hoover pledged to do all he could to frustrate them. Obviously, that included targeting their celebrity supporters.

Jean Seberg was far from the only pal the Panthers had in Hollywood; Marlon Brando and Jane Fonda gave money and enjoyed the attention of the FBI for their trouble. But neither of them were pursued with the same ferocity as Seberg. “Alleged promiscuous and sex perverted white actress,” was how one FBI memo described her, setting the tone for how the bureau would treat her.

It’s this operation against her that is the main focus of the new biopic, a state-sanction campaign of harassment and intimidation so intense that these days we’d call it ‘stalking’. Mail was intercepted, phones were tapped and she was followed wherever she went: as bad as Otto Preminger was, J. Edgar Hoover was a bigger ogre still.

Listening into a phone call, the Feds learned she was pregnant. They fed this information to a sympathetic gossip columnist, adding that the father was not her then-husband novelist Romain Gary but Raymond Hewitt, a black activist. This wasn’t just tittle-tattle: this was 50 years ago, remember, when ‘miscegenation’ was one of America’s most powerful taboos, the sort of thing that could kill a career stone dead (and worse).

Although the biopic depicts an intimate relationship between the activist and the actress, there’s no evidence that, in real life, they were anything but friends. (Estranged from Gary, her baby’s father was Carlos Navarra, a Mexican student protestor.) But the Feds were interested in intimidation, not accuracy, and there they were triumphantly successful. She gave birth, prematurely, on August 23, 1970; the child – a daughter, Nina – died two days later.

By her own admission, Jean Seberg cracked up. It became important to her to silence the rumours and, to that end, she took the tiny corpse back to Marshalltown, Iowa, for burial and to show its skin to the world. “I decided to bury my baby in my home town,” she explained in 1974. “I did the whole deal. We opened the coffin and took 180 photographs, and everybody […] who was curious what color [sic] the baby was got a chance to check it out. A lot of them came to look.”

There would be no more politics for Jean Seberg. She continued to act, mainly in Europe, mainly in unmemorable films. On August 30, 1979, she was reported missing. Nine days later, she was found in her car, dead. It was a suicide. In a press conference soon afterwards, in which he blamed the FBI for destroying her mental health, Romain Gary explained she had tried killing herself on every anniversary of her daughter’s death.

We live in a time when stories of innocents abused by controlling men resonate loudly: a ripe time for the biopic of one of the most infamous victims to land. But Jean Seberg deserves better than to be remembered exclusively for her sufferings.

She was, as the films she made show, not just a talent but a genuine, compelling cinematic presence. And certainly more than just ‘an icon’.

A European star:

Seberg’s starring role in Breathless was one of the first times an American leading actress had appeared in French cinema and from that point on her reputation in France was always much greater than in her home country.

She remained Paris-based for the rest of her life, enduring a high profile there – although she managed to evade the paparazzi in 1962, when she and Romain Gary, a Lithuanian-born French war hero, prize-winning novelist and diplomat, married in secret in a village in Corsica. There were only five other people there, including two French intelligence officers and the village mayor.

Gary, 24 years her senior, had been married to English writer Lesley Blanch (Seberg’s own earlier, two-year marriage, to French lawyer and would-be film director François Moreuil had ended in 1960, after she met Gary at a party) and his divorce came through only shortly before the wedding.

It also took place months after Seberg had given birth to a child with Gary, Alexandre Diego. The birth had been concealed and, using Gary’s diplomatic contacts, the couple were supplied with fake banns and a fake birth certificate, stating their child had been born after the marriage. The Corsican wedding location had been chosen, almost at random, by French military intelligence, to meet Gary’s wishes for a low-profile ceremony.

The marriage lasted for seven years, although the couple had many lovers – Gary is said to have challenged Clint Eastwood to a duel over an affair with Seberg (Eastwood declined). It was towards the end of their marriage that Seberg fell pregnant after a relationship with a student revolutionary – the pregnancy which was the focus of the

FBI’s smear campaign. Gary publicly claimed to have been the father, in support of Seberg.

After her divorce, she married Dennis Berry, an aspiring film director, and was in a relationship with Ahmed Hasni, an Algerian actor, at the time of her death. But she remained close to Gary, staying friends and even, for a time, sharing a flat in Paris, separated into ‘his’ and ‘hers’ portions.

Shortly after Seberg’s body was found, he told a press conference he suspected foul play in her death and denounced the FBI for their hounding of her. He is said to have kept her room in their 108 Rue du Bac apartment untouched, her letters and clothes scattered across the floor as they were the day she left. Gary was to commit suicide 15 months after Seberg, leaving a note saying that his death had “nothing to do with Jean Seberg” – a tragic postcript to her own tragic life.