Rainer Werner Fassbiner’s extreme behaviour means he left a challenging legacy. But, as a recent re-release of perhaps his finest project shows, he also left an impressive body of work. JAMES OLIVER reports.

From the vantage point of 2019, it can seem hard to believe that there was once a man like Rainer Werner Fassbinder. A film director who acted like a rock star, a marginal figure who became an art-house superstar and a man so confrontational and uncompromising that he’s still making waves 37 years after his death, Fassbinder was a cultural maelstrom of the sort it’s almost impossible to imagine today.

But once upon a time, it was possible for such a man not just to function but to thrive. During the 1970s, Fassbinder was the leading figure of his generation of German filmmakers, more celebrated in his day than peers like Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders. It helped that he was so prolific: by the time of his premature death at 37 – an Olympian-level drug intake tends to have that result – he’d completed somewhere in the region of 45 feature films and (long form) television productions, routinely undertaking two, three or even more projects a year. What’s more, he maintained an astonishingly high level of quality control too.

The work, though, is only one of the reasons Fassbinder remains so compelling. His life was a rampage, one undertaken with little conscience given to propriety or convention. His sexual tastes ranged in every direction (his first wife, Ingrid Caven, was displeased that he chose to spend their wedding night in bed with another man rather than her) and his ruinous relationships became material for his films, exposing his feelings with an almost dangerous honesty.

He was born in 1945, a doctor’s son, and raised in the stolid bourgeois respectability of Bavaria, a background he repudiated just as soon as he could. He dived into bohemian Munich to become an actor in the mid-1960s; failing to become a star overnight, he began writing and staging his own plays. Once he scraped together enough money, he started making films: the first, Love is Colder than Death came in 1969. Others followed a furious pace.

A charismatic fellow, he soon attracted followers and established what is usually referred to as a commune, although a more accurate description might be ‘cult’. Fassbinder, of course, was its leader and exerted a powerful sway over everyone else. Actress Irm Hermann reported how he commanded her to abandon her work as a secretary to appear in his productions. She obliged, and remained with him throughout much of his career, no matter that he continued to bully and abuse her.

There are no shortage of Bad Fassbinder stories. During the making of his western Whity – and yes, Fassbinder did indeed make a western – producer Peter Berling stated the director started each shooting day by ordering ten Cuba libras, nine for his own consumption, the tenth to hurl at cameraman Michael Ballhaus. And yet no-one was harder on Fassbinder than himself. Straight after Whity, he made a film called Beware of a Holy Whore about a film crew making a western not unlike Whity under the control of an arsehole film director who is a Fassbinder surrogate down to his tatty leather jacket.

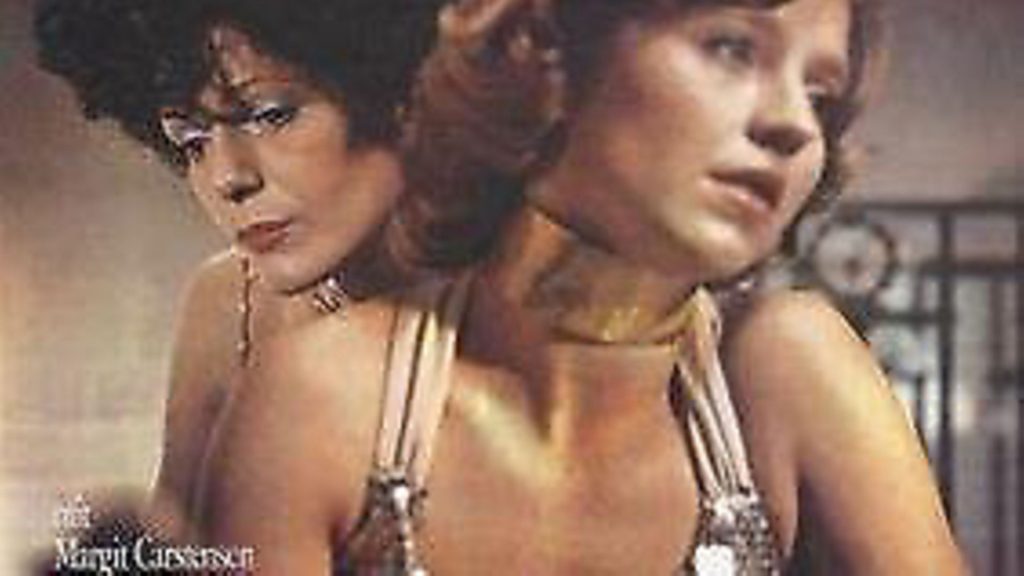

The director’s stand-ins aren’t always so obvious, but they populate his work. Take The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant by way of example. Written during the course of a single 12 hour flight from Munich to Los Angeles, it tells of how the titular designer (Margit Carstensen) is destroyed by an infatuation with a manipulative younger woman (played by Hanna Schygulla, Fassbinder’s greatest muse) that mirrors the director’s own self-destructive infatuation with actor Gunter Kaufmann.

Informed by the director’s anguish, the emotional intensity of Petra von Kant made it his first significant international success. It also demonstrated a more confident filmmaker, interested in aesthetics and drawing the Hollywood films he so loved as a youth. In particular, he developed a fascination with the work of Douglas Sirk, a German-born director who fled to America to escape Hitler, best known for ostensibly glossy melodramas whose Technicolor veneer concealed emotional turmoil.

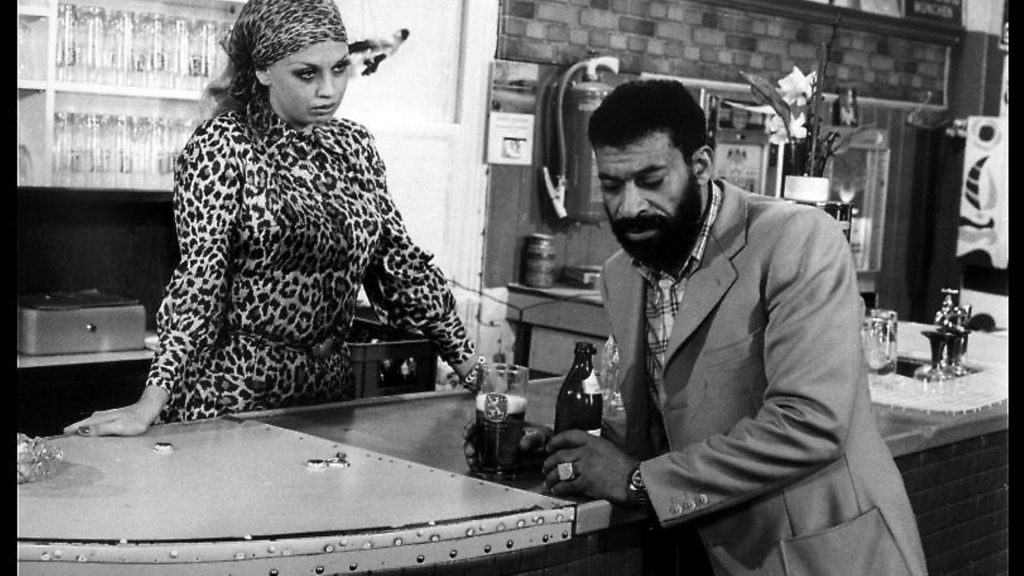

Fassbinder’s sensibilities were very different but he paid tribute to his master in Fear Eats The Soul, which consciously riffed on Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows. Both are stories of a love affair that upsets polite society; in All That Heaven Allows, wealthy widow Jane Wyman scandalises her well-to-do social circle by taking up with her gardener (Rock Hudson). Fassbinder took things further: his couple are an older working class cleaner and a young Moroccan ‘guest worker’, or Gastarbeiter, called Ali. It might just has easily been titled More Than Hollywood Would Allow.

To play Ali, he’d cast his own lover. He’d met El Hedi ben Salem in a Paris bathhouse and ordered him to come to Munich, where a tempestuous relationship began. Salem was a troubled man; quite apart from the routine stresses incurred by anyone who had to deal with Fassbinder, he had racism to contend with, and homesickness too – he’d left a wife and children behind in Morocco. Worse, he had mental health issues, problems exacerbated by the drinking and drugging of the Fassbinder circle. These problems often erupted into violence.

Tired of the endless drama, Fassbinder ended things. Salem moved to Berlin and drank heavily; one night at a bar, he got into an altercation and stabbed three men, not fatally. Fearing incarceration, he sought Fassbinder’s help – willingly granted – to escape into France. Salem continued to drink, and stabbed someone else, only this time he was jailed. Unable to take much more, he hung himself. Fassbinder didn’t find out until five years later.

Professionally, things were less awkward. His greatest success, The Marriage of Maria Braun used the framework of a melodrama – a woman waits for the return of her POW husband while achieving a measure of personal prosperity – to interrogate the West German ‘economic miracle’ or the 1950s, something that Fassbinder suggests that the country had a good deal less to be smug about than the popular mythology had it.

The Marriage of Maria Braun – glossy, accessible – turned Fassbinder into the mainstream filmmaker he’d always aspired to be, but anyone who thought he might be at risk of selling out was much mistaken.

After Salem’s departure, he’d taken up with a disturbed young man called Armin Meier. They broke up soon after the completion of Maria Braun, whereupon the devastated Meier killed himself in the flat they had once shared.

Plunged into suicidal depression himself, the director sought refuge in his work. Made in little more than two months from top to tail, In A Year of 13 Moons is a bleak film – there’s a long tour of an abattoir which suggests the psychic pain that Fassbinder was in – but perversely funny too; dark though it is, there’s also room for an impromptu dance routine.

In A Year of 13 Moons was the last time Fassbinder splayed himself across the screen so completely. Other work would follow, including some that rank among his best, but they would be less confrontational and certainly less confessional. His personal life became more settled too: he married again, to a young editor called Juliane Lorenz, and there seemed a new equilibrium in his life.

So it was that he undertook his grandest, and for many finest, project, a 13-part adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s novel of low-life in 1920s Berlin made for television. Newly-restored and recently released in a bells-and-whistles Blu Ray edition, Berlin Alexanderplatz is one of the landmarks of European television, following an ex-con as he tries to go straight with limited success. It had been Fassbinder’s dream project for many years (his occasional alias ‘Franz Biberkopf’ was taken from the novel’s hapless hero) and hints at how his art might have evolved had he lived: still drawn to the gutter but with a greater understanding of those he found in there with him, and more responsive to their plight.

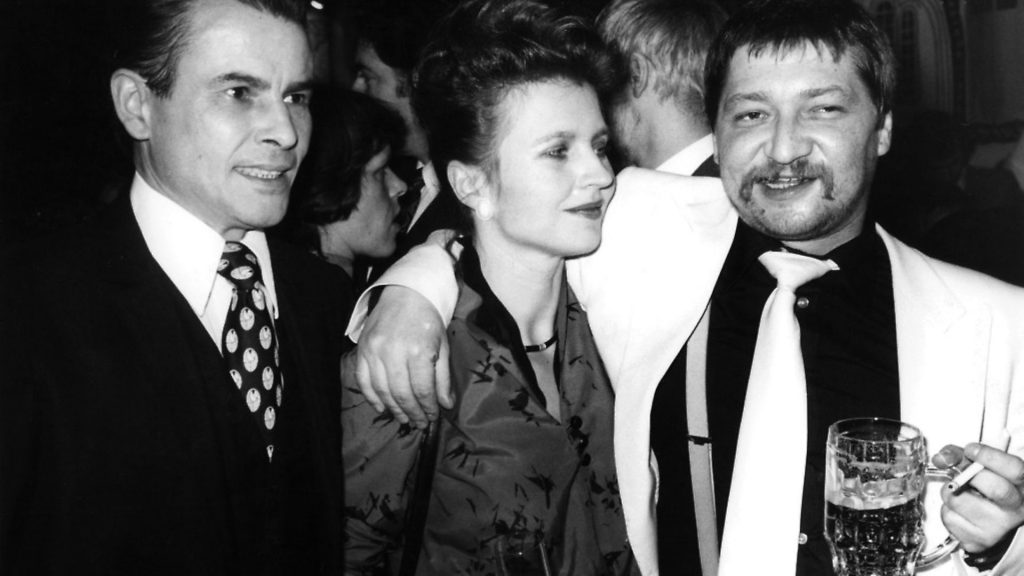

He even planned to fulfil his long-time ambition of making a Hollywood movie and began spending more time in America; his fellow German director Wim Wenders had already made the leap, although he was having difficulties – he was making a film called Hammett for Francis Ford Coppola, who was being difficult. One night an awards ceremony in Los Angeles, where Coppola was holding court, Wenders poured out his problems to Fassbinder. Then, Wenders had to calm him down, explaining that while he was grateful for his support he really didn’t need Fassbinder to find Coppola and beat him up.

But – just as Coppola remained unmolested – Fassbinder never did work in Hollywood. He died in 1982, leaving a huge void in film culture. He can seem like a challenging figure, and not just for his daunting filmography: his often repellent behaviour is even more conspicuous in this era of #MeToo. But if Fassbinder stood for anything, it was unflinching honesty. He told us who he was when he was alive, and he never asked for indulgence or forgiveness. That compulsive candour is hardly comfortable but it’s what makes the films so compelling still.

The restored Berlin Alexanderplatz is released by Second Sight; Fassbinder’s science fiction television series World on a Wire will be available on Blu-ray from February 18.