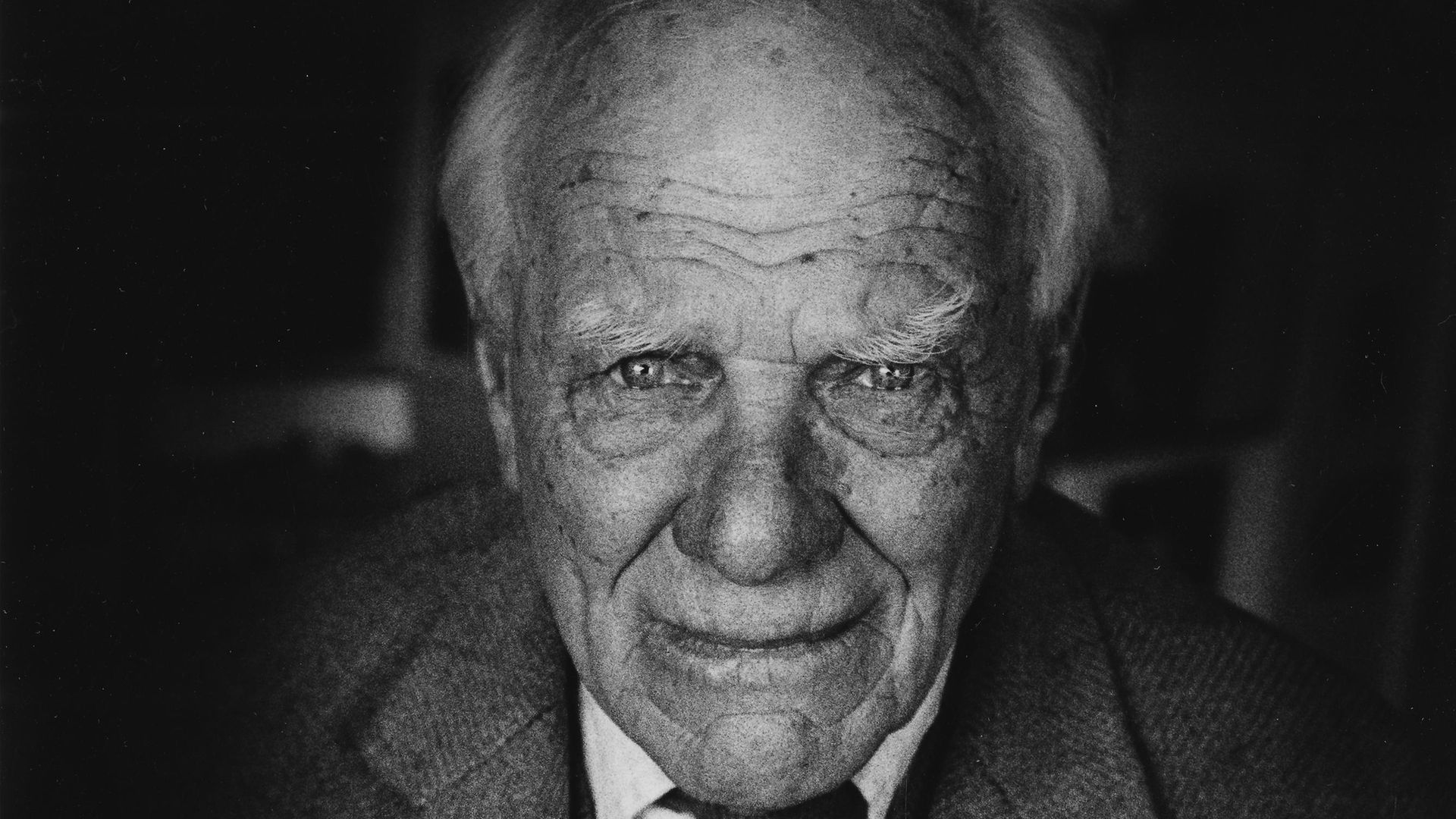

TIM WALKER remembers a meeting with Malcolm Muggeridge, an encounter which has haunted him since revelations about the journalist and broadcaster later emerged.

Malcolm Muggeridge – St Mugg, as he was known in his day – admitted to me that he had been an actor all of his life. His credits included I’m All Right Jack and Heavens Above! and what’s striking about his appearances in those classic films is how seamlessly they welded with his television journalism.

“Guilty as charged,” he cried out when I put it to him that “Malcolm Muggeridge” was no more than a part he’d played for pecuniary gain. When I asked him who he really was, he paused for a while. “Now that’s not so easy to answer,” he said eventually. “As one grows older, and one sees one’s life in perspective, one realises it’s not a question that matters all that much.”

Journalists as entertainers have always been among us. I think of Sir David Frost in That Was the Week That Was and films like The VIPs. I spotted Sir Robin Day playing himself very adroitly in a Morecambe and Wise repeat the other day, and newsreaders, such as my friend Simon McCoy in Stormbreaker, have long made it pretty obvious that what they do for a living is also just another form of acting. Boris Johnson, as a journalist and subsequently, has maybe taken performance art to a whole new level.

I met Muggeridge three years before his death when he was 84 and living in a cottage in Robertsbridge in Sussex with his wife Kitty. The encounter haunts me as it’s been revealed in recent years that he was a “compulsive groper” during his early days working for the BBC, a charge that his family accepted, although they were insistent that he later mended his ways.

Of Kitty, Muggeridge told me that she had always been “the real saint” in the relationship. I wish now I’d pressed him more on why he’d said that, but he seemed only too well aware that he’d not handled his personal life well. He’d married Kitty in 1927 when her father, a well-to-do colonel, shouted out from the back of the register office “you can still get away, Kit.” Muggeridge admitted: “Kitty’s father could see through me. I had some odd ideas about marriage at first. I believed that we should be allowed our freedom.”

He insisted it was “only talk” and that neither of them ever actually took other lovers, but he went on to say he did not consider himself to be, in terms of his adopted faith, a good Catholic. Indeed, he said he’d felt so repulsed by himself he’d tried committing suicide during the war when he had been working undercover in Mozambique. “I got rather sick of it all and swam out to sea late at night, but the bright lights of the city made me want to come ashore again.”

I asked him if his controversial opinions – he made an intemperate attack once on the Queen – were just a way of drawing attention to himself. “I don’t think I was ever controversial for the sake of it,” he said. “I’ve never felt the Queen is the slightest use to anybody and I believe that fervently. I’ve nothing against her personally, of course.”

He had what he called a deep-rooted hatred of “humbug” and that was why he’d fallen out with the Guardian, where he’d worked as their leader writer. “C. P. Scott was then its editor and he made a great thing about how his paper would never carry advertisements for alcohol and bookies because he said they were immoral. He would never admit, however, that it was advertisements like these in what was then the Guardian‘s sister paper – the Manchester Evening News – that was keeping his unprofitable paper afloat.”

His flirtation with communism had also ended in disillusionment when he travelled to Russia in the early 1930s and found the authorities indifferent to a major famine in Kiev. He said it was the last straw for him at the Guardian, too, when Scott toned down the furious reports he filed for the paper.

Then he asked me something that took me aback: “Do you ever think of becoming a journalist?” Having sat beside him for more than an hour writing down what he’d said in my notebook – and having made it perfectly clear on the phone a few days earlier I was interviewing him for a newspaper – I have to admit I found the question rather charming. I could have been any old herbert who’d wandered in for a chat and a cup of tea and yet he’d been quite so welcoming. A troubled, restless and profoundly imperfect soul, but unforgettable for all that.