Brexit has reached a crunch moment. Here Progress director RICHARD ANGELL rallies the remain troops.

Brexit is not what anyone was promised. No money for National Health Service. Immigration numbers will barely change. There is not a list of countries lining up to do new trade deals. We are not ‘taking back control’, but losing it.

Outside the European Union there are two broad futures for Britain: the Norway model or the Singapore model. Either way we become some form of rule-taker. We can stay within the European economic model of high standards for workers, consumers and the environment but let the EU27 decide the detail, or we can let corporate interests deregulate Britain in a way that would make Margaret Thatcher blush. Our reclaimed control is limited to choosing who else wields power over us.

Modern sovereignty is pooled power with those who share our values. Collaboration makes us stronger by giving us clout against those who do not share our values. The EU is an institution hated by Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin for the same reason: it erodes their desire to act with impunity. Outside of the EU, we will not have fewer allies, but weaker bonds with them and less influence over the decisions of others.

Britain has to choose its future. How much power do we wish to pool, and how much will we allow to slip away?

When she called the 2017 general election, Theresa May asked the public to strengthen her hand for a Brexit deal. The voters refused. One of the few clear outcomes of that election was that there was no faith in May to secure the best deal for the country. Now, no parliamentary majority exists what she will bring backs from negotiations. On no level does there exist a democratic mandate for the executive to unilaterally determine Brexit.

In seeking democratic cover from the House of Commons for its deal, the Conservative government will seek to pressure Labour members of parliament into support with a false sense of urgency. Time is one thing, however, that is in the government’s control. It is not tight. It is of the government’s choosing – more time can be sought with either the unilateral withdrawal of article 50 or an extension agreed with the EU27.

The government is not the only place pressure will come from for Labour MPs. Around 60 per cent represent seats that voted ‘Leave’, and many constituents wish to see their parliamentarian act on their wishes. As Gloria De Piero, an MP recently re-elected to the Progress strategy board, explains one of the most common questions she is asked is: ‘Have we not left yet?’ That impatience is understandable, and we should not underestimate the consequences of failing to honour the outcome of 2016’s referendum, as was promised.

What many hardline Brexiteers in politics do not acknowledge is that failing to secure a good deal is also a failure to honour the outcome of that referendum. A poor deal is not the best Britain can negotiate; it is simply the best deal this government has asked for. Labour must be prepared to vote down a deal, unperturbed by accusations of either betraying voters or failing to act in the national interest. It is a bad deal that betrays Leave voters and acts against the national interest.

When Labour figures such as former policy chief Jon Cruddas and now deputy leader Tom Watson supported a referendum under Ed Miliband, it was not because they wanted to withdraw but because they perceived serious changes had been made to the relationship with Europe that Britain had voted for in 1975. Regardless of consequence, the principle of tackling a democratic deficit is a noble one.

It is increasingly difficult to argue that we do not now face a democratic deficit in our future relationship with Europe: there is a real and tangible difference between the Brexit promised and the Brexit being delivered.

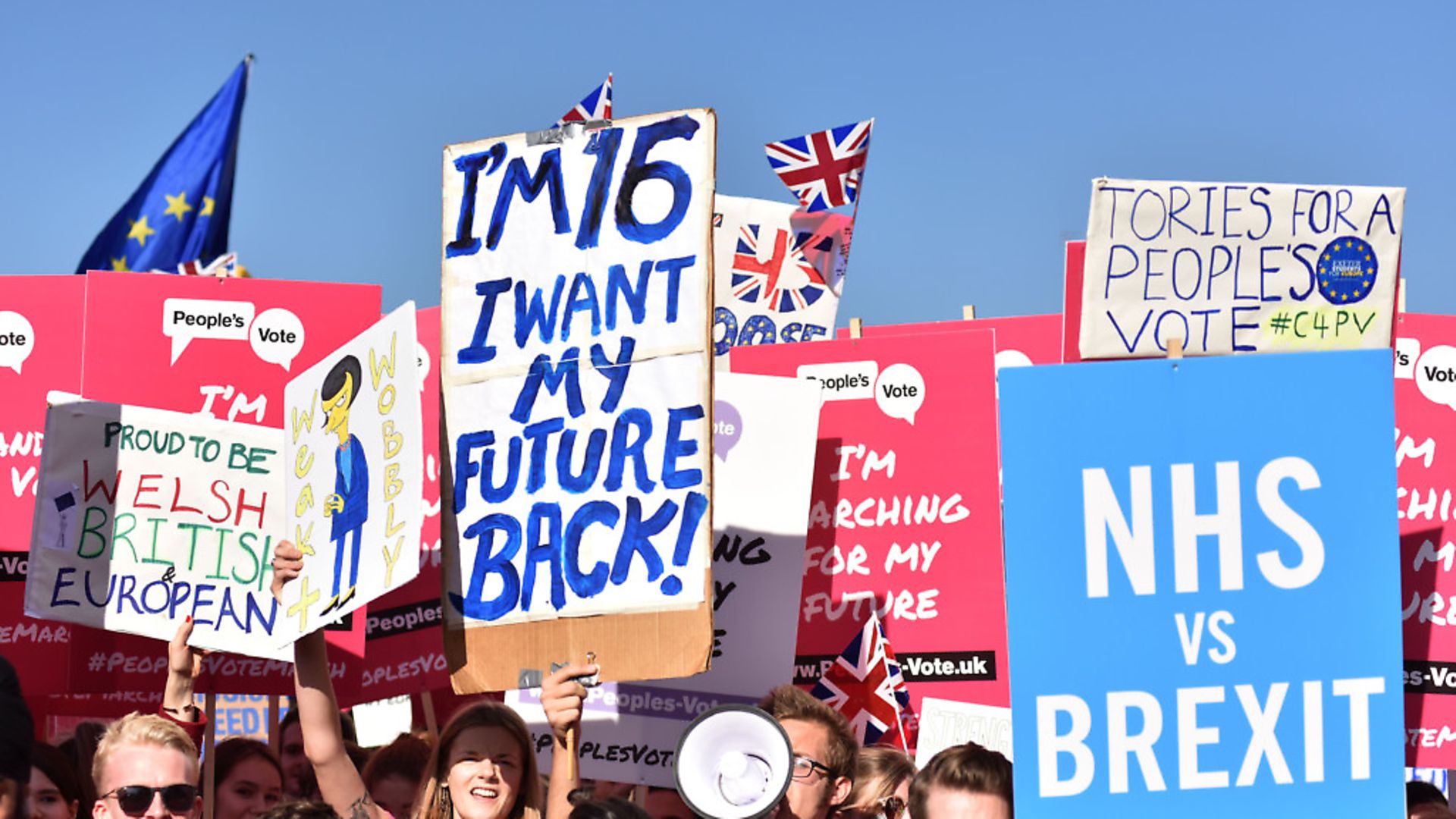

The case for a People’s Vote is mounting. That 700,000 people attended the march in London last month was surprising to supporters and detractors alike. Progress, and our LabourSay.EU campaign, were proud to play our part in leading the Labour bloc and turning the march red.

The question now is surely whether the People’s Vote campaign’s main aim is to create a progressive movement that can be mobilised post-Brexit, or focus on keeping Britain in the EU over next 12 months. If the latter truly is the goal, then it has done better than anticipated at rebuilding 2016 ‘Remainers’ into a cohesive political force, but not yet enough to win over people in places like Ashfield.

De Piero notes that the amount of ‘publicity’ and ‘airtime’ the liberal cosmopolitan crowd have been getting gives the unhelpful impression of a continuity-Remain campaign. There is certainly insufficient movement in the polls at the moment to give many sceptical MPs like her a reason to abandon their opposition to a public vote on the final deal.

Some in similar positions have chosen a different path, however. Rachel Reeves’ pro-Leave Leeds seat is another place that will decide if Britain goes along with Brexit or not, and her recently-declared support for a People’s Vote is hopefully the start of a campaign that better speaks to areas like that. Matthew Doyle, on page 24, sets out how a People’s Vote campaign can only succeed by embracing the fact that it is not the establishment position. That is the only way to get parliamentary support for another poll.

Brexit cannot give Britain any more control. Unilateral ‘control’ is not an option for a modern country that wishes to play a role in the world. We either sit at the table with like-minded Europeans and make the rules together or we shirk the responsible and be a rule-taker from our EU friends or global corporate interests. That is what Britain has control over. It should be the British people who decide.

• This article first appeared as an editorial in think tank Progress’ member magazine.