From his childhood during the Chinese Civil War to his experiences in the Second World War, Mervyn Peake’s influences are hauntingly evident in his work, much of which has just been acquired by the British Library. RICHARD HOLLEDGE reports.

Step into the shadows of “time-eaten buttresses, of broke and lofty turrets”. Meet Lord Sepulchrave, trapped in a cycle of pointless ritual, the Countess of Groan with hair which “clustered upon the pillows like burning snakes”, the “stenching cherubs” who worked in the kitchen.

This is the world of Gormenghast, a stony Gothic bubble of loathing and inexplicable ceremonial, peopled by freaks, fantasists, rogues and emotional cripples, brought together in extravagant chaos by the imagination of Mervyn Peake.

What inspired Peake to create Gormenghast, the trilogy of fantastical adventures which began with Titus Groan in 1946? How did he come to create the citadel in which the Tower of Flints “arose like a mutilated finger from among the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously to Heaven?”

A recent acquisition by the British Library of 300 illustrations and drawings by Peake will bring deeper insight to the mind of the man whose imagination, as one critic judged, “could be a fearsome place”. As well as drawings from the Gormenghast series, there are illustrations he made for his own children’s books such as Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor and Letters From a Lost Uncle. Also, fearsome depictions of the characters from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and whimsical characters from Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark and Household Tales by the Brothers Grimm.

For the first time they can be set alongside the Library’s collection of the writer’s literary archive to show how interdependent words and pictures were to his work and further establish him as a writer, poet and artist in the same league as William Blake, Edward Lear and Wyndham Lewis.

He is a hard man to pigeonhole though. Author Anthony Burgess compared the trilogy to post-war classics such as T.S. Elliot’s Four Quartets, Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and George Orwell’s Animal Farm and in a preface to the books suggested that Peake was an artist somehow separate from the concerns of everyday life. He “does not seek to highlight to investigate topical themes such as race, class and homosexuality or advance the frontiers of contemporary consciousness… his books nourish the private imagination”.

With its exotic, elusive use of unexpected phrases – flagstones sigh at every step; lying on a lily of pain – an improbable world is conjured up, in which as Burgess has it, there are “no sermons or warnings. It has absorbed our history, culture and rituals and then stopped dead refusing to move, self feeling, self motivated, self enclosed. This is the world of Gormenghast”.

There is little to suggest that the young man “on the sunny side of 22” who was feted after a successful exhibition as painter whose “versatility and imagination place him in a class of his own”, would tread these dark, “enclosed” paths.

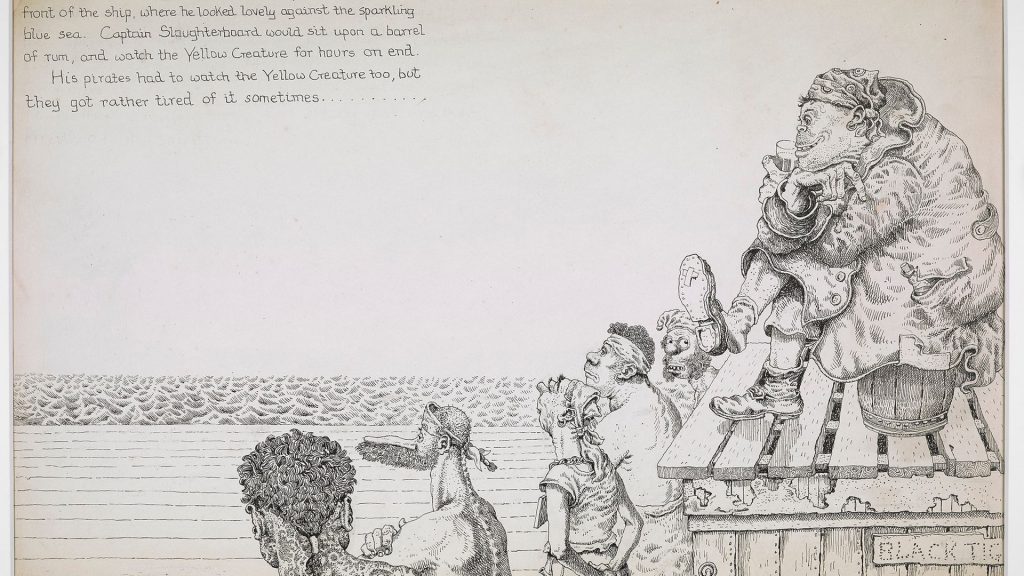

His picaresque depictions in The Hunting of the Snark (1941) of oddities with pointy noses, high foreheads and gangly limbs are still acclaimed, as are the protagonists in the surreal Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor (1939) in which a sailor and crew capture a small humanoid, the Yellow Creature.

After many adventures the book ends with the Captain and the Yellow Creature giving up their piratical adventures and settling down to fish on the creature’s pink island. The characters are all amiably grotesque, the mood whimsical.

The mood changed profoundly in the war. He suffered a nervous breakdown in 1942, partly because he could not find a role as a war artist – the War Artists’ Advisory Committee considered his work was better suited to conveying the unreal than recording facts – and resolved to replace painting by illustrating his own writings and that of other authors. The whimsy was replaced by a harsher vision, the picaresque became sinister.

Peake was already suffering from shaky mental health by the 1940s. He was to die young in 1968, aged 47, stricken with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. But his general lack of wellness might be dated back to his childhood in China. He grew up with images of a civil war raging at the time which his missionary father recorded in a series of graphic photographs, and his anxieties were exacerbated by witnessing his father perform amputations on the patients who came to his clinic.

If these distressing experiences haunted him they were little compared to the devastation he felt when he was recalled from demobilisation in 1943 and sent to the German cathedral city of Cologne immediately after war’s end.

He wrote to his wife, Maeve: “Terrible as the bombing of London was, it is absolutely nothing, nothing compared with this unutterable desolation.”

He describes the cathedral standing in stark contrast to the flattened city around it. “It is incredible how the cathedral has remained, lifting itself high into the air so gloriously, while around it the city lies broken to pieces… But the cathedral arises like a dream… a tall poem of stone with sudden, inspired flair of the lyric and yet with the staying power, mammoth qualities and abundance of the epic.”

Comparison with the “mutilated finger”of the Tower of Flints is inevitable.

Yet more affecting was his visit to the Bergen-Belsen Nazi death camp in 1945, of which his son Sebastian said: “I believe now that the Holocaust was my father’s heart of darkness.”

Peake’s poem, The Consumptive, Belsen, is a moving, bitter lament about the last hours of a dying girl – “The hour before her last / Weak cough into all blackness.”

He complemented his words with a sketch which caught the girl’s agony, her eyes dark with terror at her impending death. “Her agony slides through me,” he confessed.

It is possible that the image of Steerpike, the crafty upstart in Titus Groan, who brings chaos to the rigid protocols of Gormenghast, was influenced by his meeting in a condemned cell with one Peter Back, a Nazi sentenced to death by the war crimes tribunal for killing an unarmed US airman.

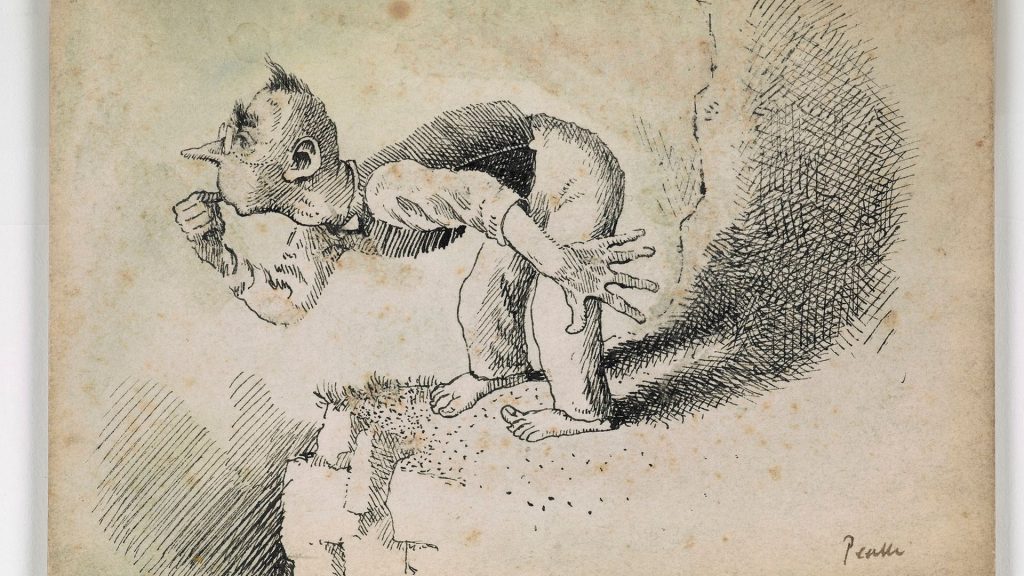

Peake would often draw his characters as part of the writing process, using it as a technique when he suffered from a creative block, and the image he created of Steerpike perfectly illustrates the interplay of his words and drawings: “High-shouldered to a degree little short of malformation, slender and adroit of limb and frame, his eyes close-set and the colour of dried blood”. The portrait entirely matches the words.

Here, indeed, is a character who, “if ever he had harboured a conscience in his tough narrow breast he had by now dug out and flung away the awkward thing”.

Peake was nonetheless versatile enough to find the humanity in any subject, even one as unpromising as a glass-blowing factory near Birmingham where he was sent to record his impressions. In The Glassblowers (1944) he described it as “a place of roaring fires and monstrous shadows” where he found “a poetry of barbarous birth”.

His illustrations have a molten beauty as elegiac as the poetry. “A lyric ease pervades their toil,” he wrote. “Their firelit bodies lordly as they blow.”

In contrast, he imbues Treasure Island, his childhood’s favourite book, with wickedness and fear (1949). As a boy he was fascinated with pirates and the British Library has acquired some of his earliest drawings of Treasure Island, one drawn when he was only 15.

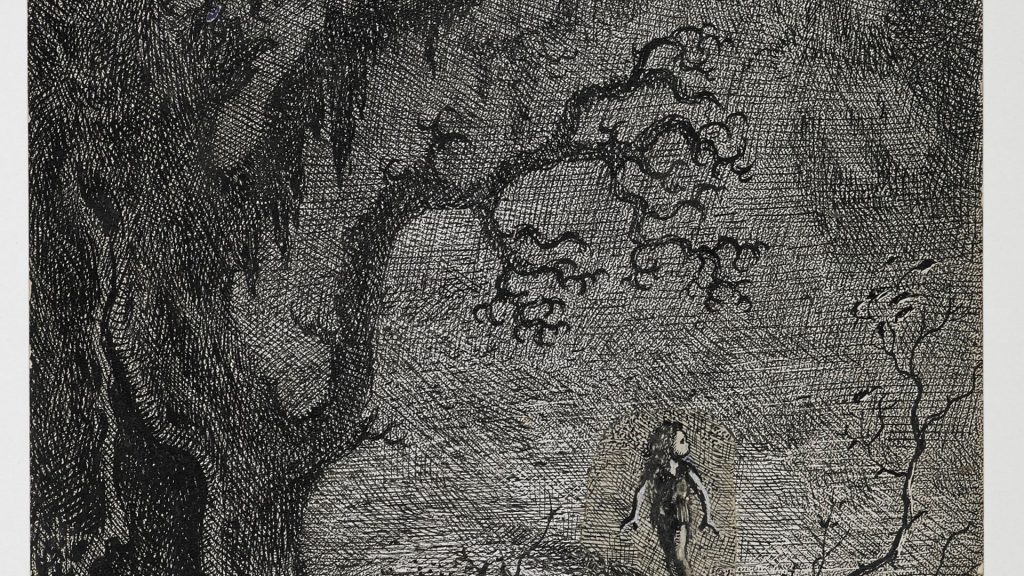

In the mature 1949 work, Blind Pew emanates terrifying malignancy, the pirate Israel Hands falls headlong from a ship’s mast into a void of emptiness, the lad, Jim Hawkins is seemingly lost in a strange sea shore ringed by massive cliffs. The Glasgow Herald newspaper wrote: “In these drawings fear, terror, evil and humour are captured, and transfixed.”

Similarly, the mysterious The Rhyme of the Flying Bomb (1947), with its felt pen illustrations, tells of a sailor wandering in London during an air raid who finds a newborn baby in the debris. Together they form their own universe, untouched by the workings of other minds, solely dependent upon themselves. It is a weird poem in which the sailor is ultimately in thrall to the infant. A violent one too. A flying bomb falls on the church where they are sheltering, killing them both.

The poem was clearly influenced by what he had seen of wartime atrocities but do those horrors also find echoes in the uneasy, fantastical world of Titus Groan? Are the labyrinthine corridors, empty courtyards, chasms and threatening turrets of Gormenghast reminiscent of Cologne where he smelt “for the first time in my life the sweet, pungent, musty smell of death?”

Whatever the secret’s of Peake’s psyche, perhaps Anthony Burgess summed up his genius when he wrote of Titus Groan: “It was the rich wine of fantasy chilled by the intellect to just the right temperature.”

The Visual Archive will be available for research on completion of cataloguing in 2022. There will be an opportunity to see highlights from the archive in future British Library exhibitions