They were put to work in the service of an inhumane regime, yet the photographers of the Soviet Union still managed to produce work of quite dazzling brilliance. RICHARD HOLLEDGE reports

Evgeniy Khaldey’s first camera was made of cardboard and his grandmother’s spectacles – perhaps, an extreme example of the challenges facing Russian photographers of the Soviet era, though Khaldey had to demonstrate his inventiveness again some years later in 1945 at the taking of Berlin.

Caught up in the heat of battle, he requisitioned a table cloth, painted on the hammer and sickle and draped it from the Reichstag, creating a photograph that has endured as a symbol of Europe in ashes, and the toppling of one power by another.

But this, and other war pictures, such as Sevastopol After Liberation – showing a couple sunbathing, improbably, amid the devastation of the Crimean city – or his portraits of Nazi war criminal Hermann Göring, counted for little once hostilities ended and the heavy hand of Stalin stifled the country.

Tass, the paper he had served throughout the war, sacked him in 1948 because, like most of the photographers who had captured, indeed celebrated, life in Soviet Russia in times of peace and recorded the triumphs of conflict, Khaldey was Jewish.

Many of his fellow photographers suffered the same fate; marginalised, impoverished and forced to take on hack work where they could.

But thanks to the collecting zeal of a contemporary, fellow photographer Lev Borodulin, Khaldey’s work, along with that of other prominent photo-journalists, was saved and is now being shown at London’s Atlas Gallery, in an exhibition, Masterpieces of Soviet Photography.

After being wounded twice and joining the assault on Berlin, Borodulin began collecting at the end of the war when he was asked to create a photographic chronicle of the battles fought by his former regiment.

First, however, aware of the hostility to Jews like himself but determined to practice his skills as a photographer, he concentrated on sport where experimentation was tolerated and ideological control was relatively lax.

He conjured up a world of muscle, grace, and panache with swooping divers, speeding skaters, parades of finely-honed athletes and in the show, Human Pyramid a great tapering pile of finely balanced athletes.

Nonetheless, the moment visa restrictions were eased, he emigrated to Israel in 1972 where he lives today, aged 95. By then his collection had reached many thousands of images.

Borodulin worked for 15 years at the magazine Ogonyok (‘Little Flame’), the Soviet equivalent of Life magazine, and knew the photographers in Moscow who shared a small, collaborative world, working for the same magazines such as USSR in Constructivism, and Soviet Photo, and the leading newspapers, Tass and Izvestia.

Not only could he tap into this close knit community and acquire their prints, he was well placed to acquire the archives of agencies which had gone out of business.

‘His main motivation was to preserve the works rather than make a profit,’ says Ben Burdett, owner of the Atlas Gallery. ‘I am not actually sure how many there are, perhaps as many as 80 to 90,000 prints which are stacked in boxes and boxes, some in a garage owned by his son Sasha in Moscow. Even he does not know where everything is because nothing has been properly catalogued.’

The works of a dozen photographers and 45 of their images are in the exhibition, with another 30-plus for sale. Prices start at £2,000.

The selection offers an intriguing insight into the Soviet Union of the 1920s and 1930s as well as the Second World War, and presents a parallel history to those in the West who invariably see the 20th century through the prism of their own concerns.

‘These photographers were asked to reflect reality in a new way, to present the new Soviet person, the new way of life and new culture,’ explains Burdett. ‘The Soviet authorities were aware of the power of the photographic image as a means of controlling the masses who, for the most part, were illiterate.

‘Photographers were expected to take pictures which symbolised collective progress, the modern proletariat and the idea of community.’

Everyone had to toe the party line, particularly after 1932 when the Communist Party decreed that photographers and artists had to abjure any fanciful notions of modernism or abstract art and follow the principles of socialist realism, glorifying Soviet life with scenes of factories proudly belching plumes of smoke, racing trains, new dams and electricity pylons bringing light and power to the masses.

The men were to be portrayed as happy, dedicated workers grimy of face and honed of muscle while the women were smiling and happy in their flowery dresses, picking tomatoes and flowers.

Typical of the time is Komsomol Member at the Wheel (1929) by Arkady Shaikhet (1898- 1959). A youth from the Komsomol movement, which educated the nation’s young into the ways of communism, is straining at a wheel as big as himself atop a machine of black girders and mighty bolts. Taken from below, a device used by many of the photographers to enhance the drama of it all, everything about the composition speaks of the worker striving for a glorious, communist, future.

Shaikhet also worked for Ogonyok where his depictions of hard-working peasants and eager soldiers heading for the front often made the cover picture, and he fulfilled the state’s demand to reflect its dynamism with images such as the starkly evocative Red Army Marching (1928) with its soldiers on skis against the shadows of wintery trees, and later in his famous Express (1939). The thrust of the locomotive’s bullet-shaped front, the steam bursting from its wheels against a lowering sky is a perfect symbol of a society powering into a socialist future.

Yakov Khalip (1908-1980) captured the power of the Baltic Fleet in the 1930s often using a bold perspective, perhaps none more than with On Guard. Big Gun, (1937), which has the small figure of a sailor in the foreground, behind him a warship but towering over both is the mouth of a mighty cannon.

Perhaps no one had a better perspective on the years of Soviet rule than Vladislav Mikosha who was seven years old when the October Revolution shook Russia in 1917 and lived to witness the end of the USSR along with the Berlin Wall in 1990. He died in 2004, aged 95.

His Heroic Sevastopol, a series of photographs of the bloody defence of the Crimean city against the Nazis, are as dramatic as anything produced by his peers. But Mikosha was careful to take pictures that reflected the good life under Stalin with the likes of Morning Exercise (1937), which depicts a keep fit class in a huge semi circle being put through their paces by a woman who, oddly, appears to be wearing a dress and sporting a scarf.

He was the first photographer authorised to use colour in the late 1960s. What a difference it makes too. In the hands of a skilled propagandist like Mikosha, scenes of every day life, people on a bus, a boy riding a tricycle, even a row of buses take on, understandably, a sense of lightness, almost cheerfulness, compared with the often starkness of the Soviet vision. (By the same token, many of the earlier monochrome works would lose some of the impact if taken in colour).

What the works prove is that despite the restrictions and demands of the state, these photographers produced work of tremendous aesthetic sensibility and innovative composition by using daring perspectives, sharp angles and shadow to a dazzling effect.

They created images which are entirely of their time; it is impossible to look at the rows of willing young people in Mikhail Grachev’s Agriculture in War Years, Schoolgirls Help Collective Farms (1941) and not know it is from that era.

For all that, their work has not really caught on with UK and US buyers and the Russians, says Burdett, would rather have a Hirst or a Basquiat.

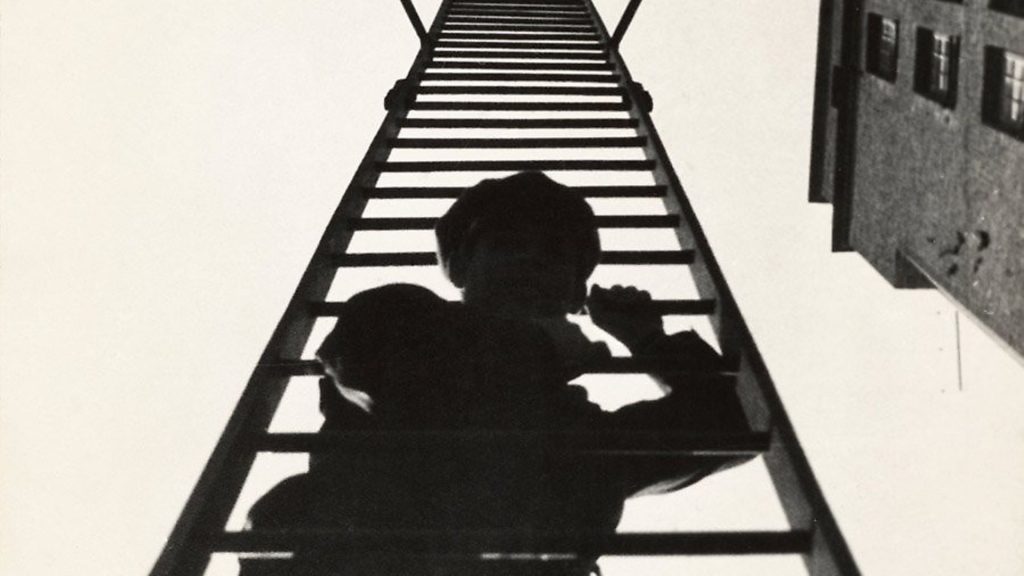

The one who has won most international acknowledgement is Aleksander Rodchenko (1891-1956), whose works have been snapped up in auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. His technique of using vertiginous angles from above or below are represented by two works from the 1920s, Fire Escape and Gathering for a Demo.

Rodchenko was an enthusiastic proselytiser for the way that the arts could express Bolshevik ideas. He observed: ‘The avant-garde of communist culture is obligated to show how and what needs to be photographed. What to shoot is something every photo group knows, but how to shoot – only a few know.’

Alfred H. Barr Jr., who became the founding director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, visited Moscow as part of a tour of Europe in 1928 and met Rodchenko and his radical group of artists and writers.

He wrote in a magazine: ‘Their spirit is rational, materialistic; their programme aggressively utilitarian. They despise the word aesthetic and shun the bohemian implications of the word artistic. For them, theoretically, romantic individualism is abhorrent.’

Despite that apparent lack of enthusiasm Barr bought several artworks by Rodchenko and his wife which now reside in MoMA’s permanent collection,