Permanent Midnight, TV writer Jerry Stahl’s book chronicling his drug habit, is now 25 years old. But it has lost none of its power, says RICHARD LUCK, who credits it with helping him sober up.

Back when they were a double act, Stewart Lee and Richard Herring performed a highly entertaining sketch comparing the hostage diaries of Brian Keenan and John McCarthy. While Lee’s approximation of Keenan’s recollections featured the dark, stark poetry of his memoir, An Evil Cradling (‘Breakfast… even the simple act of nourishment has become an instrument of torture’), Richard’s take on Some Other Rainbow accurately mimicked McCarthy’s air of an upbeat pupil at a less-than-pleasant public school (‘Breakfast with Brian again… grumpy pants!’).

Anyway, my reason for mentioning this is to make the point that addiction memoirs can also be divided into two distinct types: first off, there are the self-flagellating autobiographies in which each new chapter represents a fresh level of drug hell; and then there are those surprisingly sunny accounts in which the author’s concerns with addiction are but an amusing obstacle to overcome – A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Pharmacy, if you will.

The books that best buck these unfortunate trends invariably seem to be penned by people who write for a living. David Carr’s The Night of the Gun, for example, sees the much-missed New York Times contributor eloquently re-examine a past that, as per the book’s title, once saw him pull a revolver on a friend in the pursuit of coke, his narcotic of choice.

Permanent Midnight, meanwhile, is television and film writer Jerry Stahl’s tale of how, while he was earning $5,000 a week writing shows like Moonlighting, he was blowing $6,000 a week on heroin and, later, cocaine.

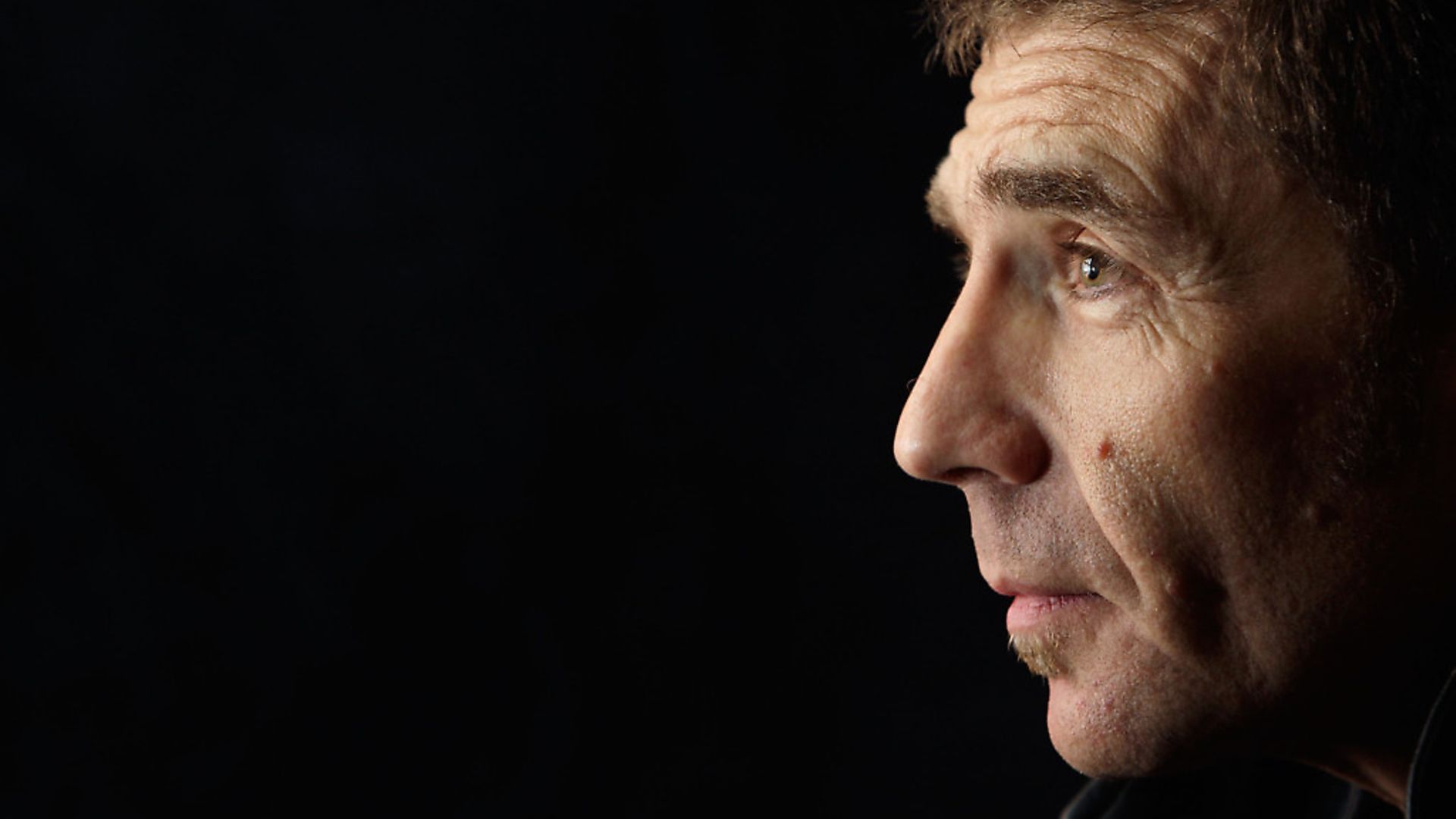

Re-reading Permanent Midnight today, 25 years on from its publication, it’s hard to believe that Stahl is still with us. But not only is he surviving, he’s positively thriving. Besides a TV credit sheet that includes CSI, Maron and the Golden Globe-winning Escape at Dannemora, he’s published the novel Happy Mutant Baby Pills and I, Fatty, a fictionalised autobiography of silent film actor Roscoe Arbuckle, plus a second volume of memoirs, 2015’s OG Dad, in which he recounts the occasional pain and abundant pleasure of becoming a father for the second time in the shadow of his 60th birthday.

Today’s Stahl is a very different person from the man we meet at the beginning of Permanent Midnight. Born in 1953 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, his father was David Henry Stahl, a Russian immigrant who, through his intellect and impressive powers of perseverance, came be to appointed a circuit judge of the United States Third Circuit Court of Appeals. Nominated by Lyndon Johnson, David served on the court from 1968 until his untimely death in 1970.

Having driven home listening to a ball game, the elder Stahl was found slumped in his garage with the doors closed but both the radio and the engine still running. The papers claimed his death was an accident. Jerry Stahl, who also lost his beloved dog in the tragedy, would grow increasingly convinced that his father had taken his own life.

With his father’s passing doing irreparable damage to the mind and demeanour of his mother – Florence Stahl’s long day’s journey into night is catalogued in Permanent Midnight – Jerry swapped the misery of home for the promise of New York where he embarked on a writing career. Early gigs included penning the articles in porn magazines that nobody reads, and Stahl found his way to Dayton, Ohio, where he worked for Larry Flynt. Indeed, Stahl was on hand at the birthday party where the wheelchair-bound pornography publisher unveiled a replica of the Kentucky shack that he had grown up in, an incident that is recreated in the Oscar-nominated movie The People Vs Larry Flynt.

Before long, Stahl had gathered up his electric typewriter and set course for California.

If there’s one thing that’s well known about Stahl, it’s that he wrote for ALF, the sitcom about a wise-ass alien that was quite the ratings hit in the late 1980s. As the man himself is keen to point out, he didn’t actually write that much for ALF.

Stahl places rather more stock in his having served on Moonlighting’s writing staff, and Permanent Midnight includes a wonderful account of a party at Cybill Shepherd’s house where the notoriously difficult leading lady proves to be a complete doll and Stahl gets into a dilly of a pickle while trying to raid her bathroom cabinet.

How to loot a pill cabinet without getting caught is but one of many fascinating things we learn over the course of Permanent Midnight. Further QI-worthy material includes Mickey Rourke’s fondness for toy soldiers (he spends five hours banging on about his collection when he should be promoting Angel Heart) and the fact that, even with a lot of heroin in your veins, you can jog five miles during the hottest part of the day in Los Angeles.

As you might have figured out by now, Stahl isn’t your average junkie. For one thing, while he has no qualms about injecting and ingesting whatever narcotics he has to hand, he’s a stickler for healthy eating and a big believer in the restorative powers of wheatgrass. He’s also a fitness fanatic, hence all the jogging.

And he was married. Yes, on top of everything else, Stahl was betrothed to an English woman who was in such dire need of a green card, she was willing to pay a man she barely knew $3,000 to get wed.

Despite the atypical nature of their union, love of a kind blossomed between the Stahls which in turn led to the arrival of a daughter. Stahl has since written that Stella – now in her thirties – is among the greatest things to have happened to him. However, being a husband and father weren’t sufficient responsibilities to help him get straight. On the contrary, the infant was often an inconvenience, an unwelcome presence when he was in West LA trying to score.

Driving round the City of Angels’ meanest streets with a baby on board is just one of Permanent Midnight’s many high/low lights. The aggressive German woman who insists on taking her heroin anally, Stahl’s stint flipping burgers while attending rehab in New Mexico, the attractive fellow recoveree who attends their trysts dressed for church in the hope of appeasing her boyfriend – the hits just keep on coming. As do the hits.

Rather than just cataloguing Stahl’s path of self-destruction, let us instead fast forward to Permanent Midnight’s sick-flecked, seemingly hopeless finale. (Note: what follows ought only to be considered a spoiler if you’re the sort of person who reads a first-person account of an encounter with a man-eating lion and wonders whether our hero will survive to tell the tale.) We’re in Los Angeles in the wake of the Rodney King verdict and Stahl is holed up in a garage belonging to – of all people – Mark Mothersbaugh, co-founder of the band Devo and soundtrack composer.

With the last of his supply gone and the city burning around him, the writer returns to consciousness to find himself caked in mud and vomit. With his host away, Stahl is left to stagger about the yard in the hope of getting clean. Chancing upon a garden hose, he raises it above his head and the water runs down his body, removing the dirt while, above him, helicopters survey a city in the midst of a nervous breakdown.

It’s hard to imagine how the end of Permanent Midnight could possibly be more downbeat. Such is the power of its gut-punch, it takes a minute or two to remember that what you’re reading is an autobiography. As such, what initially seems the most depressing finale imaginable is but the rock bottom from which Stahl made a remarkable recovery.

Not that everything clicked into place the moment Stahl began work on Permanent Midnight. As he recalled in a 2013 interview, ‘I relapsed while writing the book. In going back to that arena, you have to lean back into the abyss as far as you can without falling back in. It’s a dangerous endeavour.’

In the 20-odd years since his last drug adventure (‘For me now, the final frontier is sober living’), Stahl has enjoyed the sorts of happiness and success that are beyond a junkie’s comprehension.

The excellent albeit underrated HBO drama Hemingway & Gellhorn, Liev Schreiber’s Chuck Wepner biopic The Bleeder, a phenomenally well-paid gig scripting Bad Boys II – all wonderful things that would’ve been denied the man who messed up his dream job writing the original Twin Peaks because he was up to his thighs in his drug habit.

And then there’s 1998’s movie version of Permanent Midnight. Written and directed by David Veloz (who’d previously worked with producers Don Murphy and Jane Hamsher on Natural Born Killers), the picture stars Ben Stiller as Stahl, Elizabeth Hurley as his first wife, the superb Maria Bello as his rehab squeeze Kitty, and Owen Wilson as a composite of Stahl’s various drug buddies. Featuring cameos from Connie Nielsen, Fred Willard, Cheryl Ladd, Charles Fleischer, Janeane Garofalo and Peter Greene together with reimagined versions of both ALF and Moonlighting, it’s refreshingly faithful to the subject matter and does a good job of neither glamorising nor demonising the drug addicted.

Best of all, however, is the manner in which the writer pops up in his own story. In the book, Stahl recalls an encounter with a world-weary doctor at a methadone clinic who held out little to no hope for his recovery. In the film, the physician is played by Stahl.

The film marked the beginning of a beautiful friendship between Stahl and Stiller, the fruits of which include the aforementioned prison break TV series Escape To Dannemora. Jerry also served as the Zoolander star’s best man when he married fellow actor Christine Taylor.

But what is the reader meant to make of Stahl’s skag to riches story? In my case, Permanent Midnight was the perfect accompaniment to my recovery. In addiction, one of the keys to improved health is spending time with like-minded people.

For the most part, this means attending meetings. And for those moments when AA wasn’t in session, Stahl’s book was on hand to remind me that the moment passes, that the very worst can be overcome and that, no matter how fond one’s memories of indulgence might be, the awfulness of what came afterwards should be enough to negate them.

‘It doesn’t matter how much stuff you have on the table, you’re always thinking about what you’ll do when its gone’ – only an addict understands ‘logic’ of this sort. As someone whose time in rehab left me in no doubt that people in recovery are the best placed to help those wanting to recover, Stahl is like the friend who jumps down into a hole to lead a stranded man to safety; the sort of guy whose experienced permanent midnight but has come out the other side and now wants to share the news that the sun also rises.