As the World Cup gets underway, IAN WALKER asks why Russia, a country responsible for such great art, has produced such terrible leaders.

The opening scene of the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece Andrei Rublev is of a man taking flight in a balloon in medieval Russia.

We first see the man, seemingly panicking but determined, rowing across a river in a coracle. He is making his way to what looks like a church tower where a group of people are holding thick ropes tethering a huge balloon to the top of the spire.

Soldiers are trying to force these people to let go of the ropes. But the man scuttles past their struggles and scrambles into a rope basket before cutting the balloon free. He shouts in delight as the inflatable – a rough-looking thing, sewn out of animal hides – breaks loose from the earth and floats away.

We see what the balloonist sees; the expanse of the Russian landscape, the steppes and the lakes rolling away towards eternal skylines. The people below look like characters in a Bruegel painting; they are small but distinct and busy in their lives. This balloonist, albeit temporarily, is free and God-like.

In this scene, he is like an artist, and we can assume this balloonist is how Tarkovsky saw himself, as someone who can see the vast Russian scale and scope of everything; the steppes, the waterways, the lives of serfs and soldiers.

And then the balloonist comes crashing to earth – he is back crawling in the mud, once again hemmed in by that self-same scale and scope of the steppes. He is back among the ordinary lives of those rooted to the soil. If this balloonist was an artist who soared above the world, he is now also an artist who is back embroiled in the quotidian.

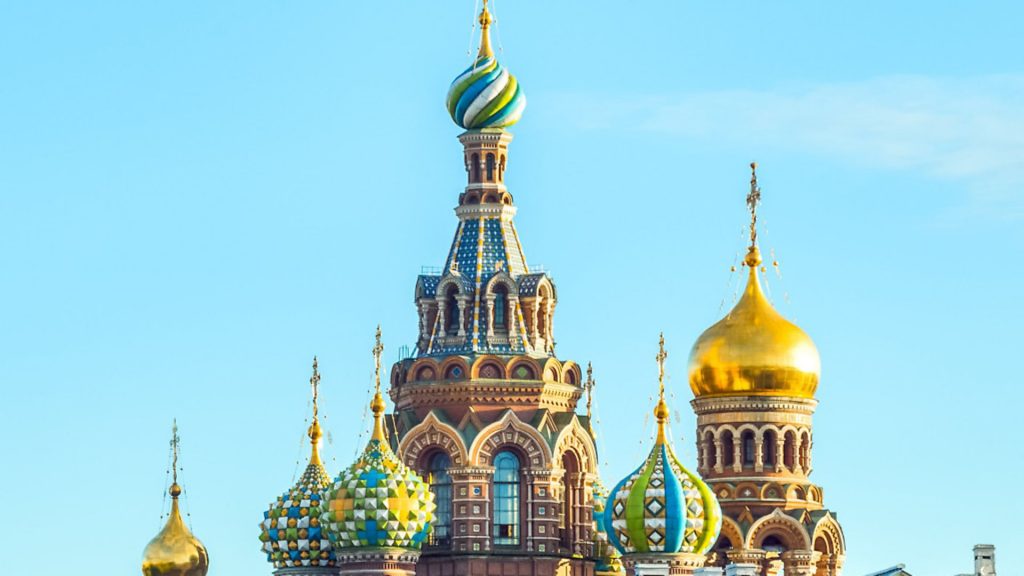

And this is what the greatest Russian artists do (and by ‘artists’ I mean painters, writers, poets, filmmakers and composers). The greatest Russian artists can deal with both the epic and the every day almost simultaneously. They can aspire to be God-like in their vision and then roll about in the mud. In their imagination and in their work they can hold all those huge contradictions that have made Russia was it is – between East and West, Europe and Asia, enlightenment and religion, European royalty and Boyar, Tartar or Mongol tribal traditions; between the neo-classical facades of St Petersburg and the onion-topped churches of Moscow; between intense isolation and introspection and endless landscapes or numberless crowds; between extraordinary wealth and poverty; between feast and famine.

These contradictions are seen in Tarkovsky’s films as they are seen in the novels of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, Gogol and half a dozen others, and in the paintings of Chagall or Kandinsky, the films by Eisenstein, the poetry of Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva, and the music of any number of composers from Tchaikovsky through to Shostakovich.

All these Russian artists have produced work that embraces all the contradictions that make Russia what it is, and almost all of them have done so in ways that elevate the specific – something innately Russian – and made it universal. The novel War and Peace contains all life; Chagall gave love its clearest visual expressions (and, by chance, juxtaposed it against hatred’s clearest demonstration, the Nazi eradication of Shtetl culture); Dostoevsky defined introspection in a new terrifying, urban, modern world; Eisenstein carved up experience in the editing suite so we can see ourselves more clearly.

Russian artists have explained and interpreted their country in nuanced, vivid and precise ways again and again and again. It is one of the great national artistic traditions, and so much of this work has become something universal.

But this raises a question: how is it that a country that has produced such great artists, all of whom are able to hold so much of what makes their country what it is in their imaginations, can also produce such terrible politicians? And these are truly terrible politicians – not terrible as in inept, in the English manner, or high-handed in the French way, or sleek and vacuous in the American way – but vain, dangerous, bullying, deceitful and occasionally murderous.

Why is it that for every Russian artist who can deal with the nuanced subtitles that come with the contradictions at the heart of what their country is, we have a Russian politician who lies about what Russia is? How is it that for every Russian artist that can find the human in the messy complexity of modern society we have a Russian politician capable of terrible deeds?

It does seem that Russia, over the last few centuries, has been a land of terrible politicians and great artists – that for every Tsar Nicholas II there is a Dostoevsky; for every Tarkovsky, there is a Putin; for every Tolstoy, a Stalin.

It was the former Everton and Wales goalkeeper Neville Southall who recently summed up what many football fans are thinking about the World Cup – ‘it’s in the wrong country’. On the one hand, it’s all very exciting – who doesn’t love a World Cup? But on the other hand, there is a concern about the hosts.

His specific worry was to do with sexual politics and the Putin government’s criminalisation of homosexuality. Southall’s suggestion on Twitter, which was that England should send an LGBT team to the World Cup, was a good gag. It showed up Putin’s Russia for the illiberal, intolerant state that it is.

And, of course, there are plenty of other concerns about apart from questions of sexual freedom. Russia is a country that invades its neighbours; its democratic process has been twisted to turn each presidential election into a coronation, while the democratic processes of other countries are interfered with; critics are criminalised or worse; and, most chilling of all, Putin seems to believe that the truth is something that can be managed.

Concern’s about Putin’s fast and loose relationship with the truth – when stacked up against rigged elections, Russia’s number of murdered journalists, and invasions – may seem misplaced. But it is this ability to lie, to fix reality to fit what Putin wants, that underlies everything. It is this deceitful world view that facilitates war, seeming indifference to the occasional murder and a sly and coercive foreign policy.

It is a worldview that seems almost innate within the tradition of Russian political leadership. And it may be the case that all those contradictions, which have unpinned so much great art in Russia, also underpin why so many Russian political leaders have been so terrible and have so often struggled with honesty.

Art can move around the truth; it can investigate it, mock it. It can hold up two seemingly true things simultaneously, it can explore contradictions. Politics does not have that freedom because politics is about action, agency and getting things done.

But political expediency does not make those contradictions go away. So, for example, Putin wants to be liked by the West and be seen by its leaders as an equal. But he can draw on massive populist support tied to Orthodox traditional values within Russia, and this he does by despising western liberal values about sexuality, immigration and gender. So here you have two contradictory things right at the heart of what modern Russia is. The only way a Russian politician can make such a schism work is through deceit. This schism at the heart of Russia has been there since the birth of the modern nation under Peter the Great (1672 – 1725). He was a europhile, obsessed by the political, artistic, military and philosophical culture of Western Europe. He looked to London, Paris, Amsterdam and Venice for inspiration and had the vision to build a great city on the edge of the Baltic.

St Petersburg would become one of the great European cities – an enlightened place of proportioned buildings, planned boulevards, trade, learning and political power which would be open to the West and open to the world. It was built in a ridiculous place, in a swamp on the edge of a sea. Mosquitos plagued it in the summer, and it was prone to floods. In winter, the sea would freeze and the ice would split the wooden shacks that the first people – the workers who would build the city – lived in.

In the first years of the 18th century, amid this mud-clad land which was barely distinguishable from the sea, you would see bewigged and frock-coated engineers, architects and planners from the Netherlands and London and Paris, all attempting to build something solid and permanent in this chaotic and seemingly-uninhabitable place.

There was delusion in Peter the Great’s aspiration for this city of the early Enlightenment, because Russian was not an enlightened county; nor was it a European country.

Its culture, centred on Moscow, was rooted in something more Eastern, more Asiatic; its onion-domed churches and ornate palaces had more to do with Samarkand than Stockholm. Much of the aristocracy came from the Boyar, the ancient, feudal, Slavic tribes.

This Russia was a world of serfs and priests and men who behaved like medieval warlords

Peter the Great was opposed to this Slavic, Asiatic world. He was a pious man, but he separated the church from the state. He created a new royal court and drew members of the aristocracy around him, effectively creating a new class of oligarchs. He even taxed beards in an attempt to modernise Russia.

So here, at the birth of modern Russia, we see that schism, between east and west, between competing ideas of what Russia is. Moreover, we can see how that schism takes on the form of something unreal: a city that shouldn’t really exist, a city born of vanity – a delusion. It was also a city whose political existence was an act of incredible violence against the Russian people. To build his city Peter drafted in armies of serfs who had to work in terrible conditions to try to make Russian ‘European’. To stop flooding, the city had be raised on banks of rubble – the serfs who died building the city were buried in these rough foundations, supposedly in their thousands.

This contradiction at the heart of what Russia politically became can also be seen the lives of those new oligarchs. One of the most powerful families was the Sheremetev family, which became so rich under the patronage of the Tsars that money became meaningless. Their wealth came to be exceeded by their debts, but this did not matter. This Russian aristocracy enjoyed a peculiar existence free of economic constraints and rules (until the Russian Revolution of 1917, when their accounts were more than settled).

The Sheremetev family’s palace in St Petersburg was known as the Fountain House. A Baroque palace, built on land by a creek donated by Peter the Great to the family in 1712, was European in design. Its public rooms aped those found in Paris or London, but alongside them were the private quarters, and these – with their open hearths, carpets, icons and chapels – felt more Russian. The public face of power was European. The private space of power was Russian.

Centuries later, after the Russian Revolution, the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova would live in an apartment in this palace. She was one of Russia’s great poets of the last century. Her work, often intimate and personal, stood in great contrast to the sweep of history which devastated her life. People she loved were murdered or imprisoned by the Soviet authorities and how she survived, rattling around, in fearful isolation, in her rooms in an old palace in St Petersburg is almost a miracle.

Akhmatova’s poem Petrograd 1919 (Petrograd was the name given to St Petersburg after the Revolution, before it became Leningrad) describes that schism at the heart of Russia. Like Tarkovsky, she could, as an artist, map out the very contradictions that existed in the Russian soil and the Russian soul, that made the country what it was. Russian politicians were unable to do that.

They wanted to crush those contradictions. Her brutal and tragic life was a testament to that.

So here we are in 2018 with the World Cup being held in a country that seems to be returning to those same deceitful political practices that made the last century what it was in Russia. The best thing to do is to probably just put that all to one side and just enjoy watching all the various shenanigans until Germany lift the trophy.

But if you are going to give some thought to the host nation, skip the politics and turn to the art. None of this art is easy – the novels are huge and the films are slow. But if you make the effort it is worth it because Russian art is a better measure of that country than its politics – and the Russia you find in art is a better Russia than the one that politics wants to assert.