A city with a musical pedigree to match any, Sheffield is still producing acts that could not have come from anywhere else, as Sophia Deboick reports

Sheffield was long a place people wanted to escape. Its status as Steel City predated the Industrial Revolution, with Chaucer mentioning a Sheffield ‘thwitel’ (knife) in The Reeve’s Tale.

With a reputation as a grimy, slum-filled city, even by 19th-century standards, when it lost 3,000 homes in December 1940 it was ripe for redevelopment and the city became as synonymous with post-war brutalist architecture as it was with steel. Later, the 1950s Park Hill estate, modelled on Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation building in Marseille and famous for its ‘streets in the sky’, came to stand for urban decay and the dashing of utopian hopes as the steel mills began to close and economic and social decline kicked in.

While Sheffield had already made notable contributions to music, with Dave Berry, Joe Cocker, Tony Christie and Paul Carrack among its famous sons, it was only from the late 1970s that the music coming out of the city began to reflect its gloom and heavy industry. A generation of young Sheffielders took the stark electronica coming from continental Europe and made their own electronic music, marked by both the city’s tough spirit and escapist ideas of technology, travel, education and romance. In the last 40 years Sheffield’s musicians have been more invested in where they came from than those of perhaps any other city, their lyrics laced with geographic namechecks and local dialect, and collaborations between them resulting in unabashed celebrations of this unique place.

Phil Oakey was working as a porter at the burns unit of the Edwardian Fulwood Annexe hospital in the Sheffield suburbs when Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh asked him to join their nascent band, The Future. The pair had begun their musical experimentation at the Meatwhistle arts workshop run at the former Sheffield School Board building in the city centre and the band, rechristened The Human League, played their first gig at Psalter Lane Art College in June 1978, just ahead of the release of their debut single Being Boiled. That uncompromising record fully betrayed the influence of Kraftwerk. Perhaps not uncoincidentally, it failed to chart, but the band became prominent on the city’s underground scene, of which the Polytechnic Students’ Union was another key venue.

While Ware and Marsh parted company with Oakey in late 1980, the Human League were hardly over. Oakey recruited a band, along with two girl backing singers he saw dancing at the Crazy Daisy nightclub on the High Street, and released Dare! in late 1981. A No. 1 album, it spawned four hit singles, including 1981 Christmas No. 1, Don’t You Want Me?. Ranging from upbeat pop to the bitter irony of The Things That Dreams Are Made Of, it all had a distinctive metallic sheen. Despite breaking America, with both Don’t You Want Me? and 1986’s Human topping the chart there, and Oakey and Giorgio Moroder’s movie tie-in, Together in Electric Dreams, making a US Top 20 hit in 1984, the band have remained true to their Sheffield roots. A 2001 album, Secrets, included The Snake, about the journey west to Manchester via Snake Pass, and instrumental Ringinglow, named after a village on the outskirts of the city.

The early Human League’s dystopian futurism was echoed by Cabaret Voltaire, from the industrial experimentation of Nag, Nag, Nag (1979), to the more mainstream Sensoria (1984), the video for which included the Tinsley Viaduct cooling towers, and the Hill Top Chapel, Attercliffe Common, just outside their native Sheffield. Clock DVA, formed by former The Future member, Adi Newton, also represented electronic gloom, while the Comsat Angels were no less murky guitar-based post-punk. But other Sheffield bands produced more upbeat fare. The Human League’s Ware and Marsh had gone on to form Heaven 17 with Glenn Gregory, and while they took their name from the bleak A Clockwork Orange and their 1981 debut single (We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang wasn’t exactly light in theme, 1983’s Temptation was baroque pop drama, peaking at No. 2. ABC, whose core hailed from Sheffield, had already gone Top 5 the previous year with the euphoric The Look of Love from their pop masterpiece The Lexicon of Love, and Sheffield’s place in the seething brilliance of the early 1980s pop charts was prominent indeed.

But Sheffield music in the eighties wasn’t all about synth-pop. With the founding of Warp Records in the back of a Sheffield record shop, and its 1989 maiden release, the seminal techno track, Track With No Name, under the moniker Forgemasters (nicked from heavy engineering firm, Sheffield Forgemasters), Sheffield claimed its place in rave culture. One local band was also making major moves on the world of bombastic rock. Def Leppard were pegged as part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, but they fully embraced the American metal-lite idiom. Having met at Tapton School in the Sheffield suburbs, Leppard’s 1981 album, High ‘n’ Dry, was produced by industry mogul Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange, and the band were troubling the US Top 20 long before they made an impression in the UK. In terms of international reach, they are the most successful band to ever emerge from the city.

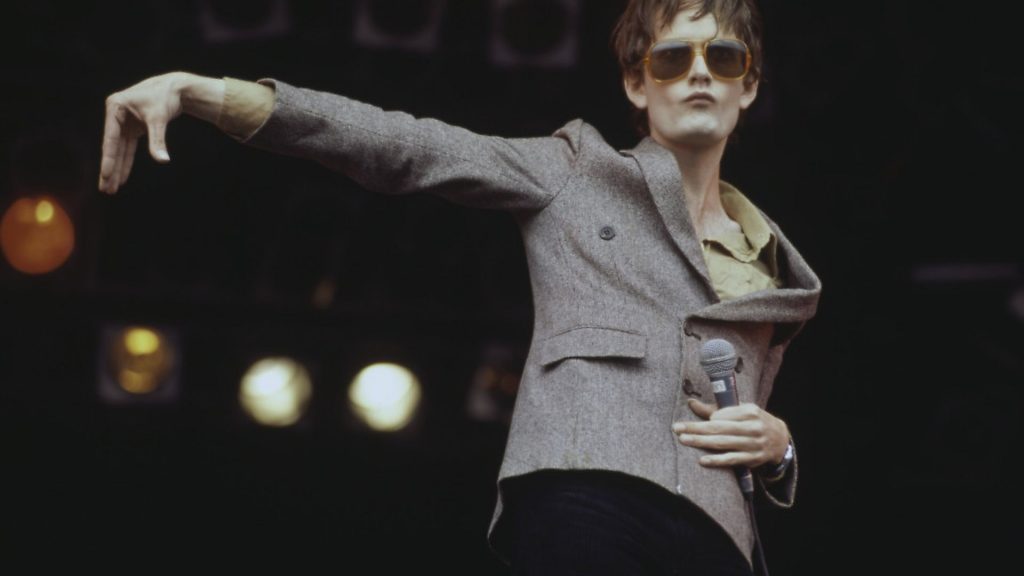

But, for Sheffield itself, another band was far more significant than the unit-shifting Leppard. Pulp cut their teeth at venues like the Studio at the brutalist Crucible Theatre and the upstairs room at the Hallamshire Hotel, making kitsch, an art school knowingness and slightly filthy kitchen sink drama their stock in trade. The teenage love triangle of Babies, the single that marked the end of their early, obscure period, was set on suburban Stanhope Road, and the experience of the city, just like frontman Jarvis Cocker’s unmistakably Sheffield accent, ran through everything they did. Common People’s line “Rent flat above a shop” was reflective of the Division Street housing association flat above a sex shop rented by band member Russell Senior, while Mis-Shapes charted the inter-gang rivalry between the self-educated working-class misfits and violent ‘townies’ of the band’s youth. The outspoken and erudite Cocker has gone on to become one of the leading cultural figures in Britain and such a Sheffield treasure that in 2016 he recorded the announcements for the city’s tram system.

Competing with Cocker for the title of ‘Bard of Steel City’ is Richard Hawley, Pulp’s sometime touring guitarist, late of the Longpigs, a band whose debut single, She Said, was a satisfying riot of crunchy guitars at a time when the waning days of Britpop had seen a turn towards the insipid. Hawley’s golden-voiced, Scott Walker-inspired retro romanticism has been completely steeped in Sheffield mythology. His 2005 album, Coles Corner, was named after the former site of the Cole’s Brothers department store, knocked down in 1969, but still referred to as ‘Coles Corner’ by those born and bred in Sheffield and therefore a symbol of the power and tenacity of localness. His Lady’s Bridge (2007) referenced the oldest bridge across the River Don in the city, while Standing at the Sky’s Edge (2012) was inspired by the hillside area hosting crime-ridden tower block estates in Hawley’s formative years – the title was later used for his 2019 musical about the Park Hill estate.

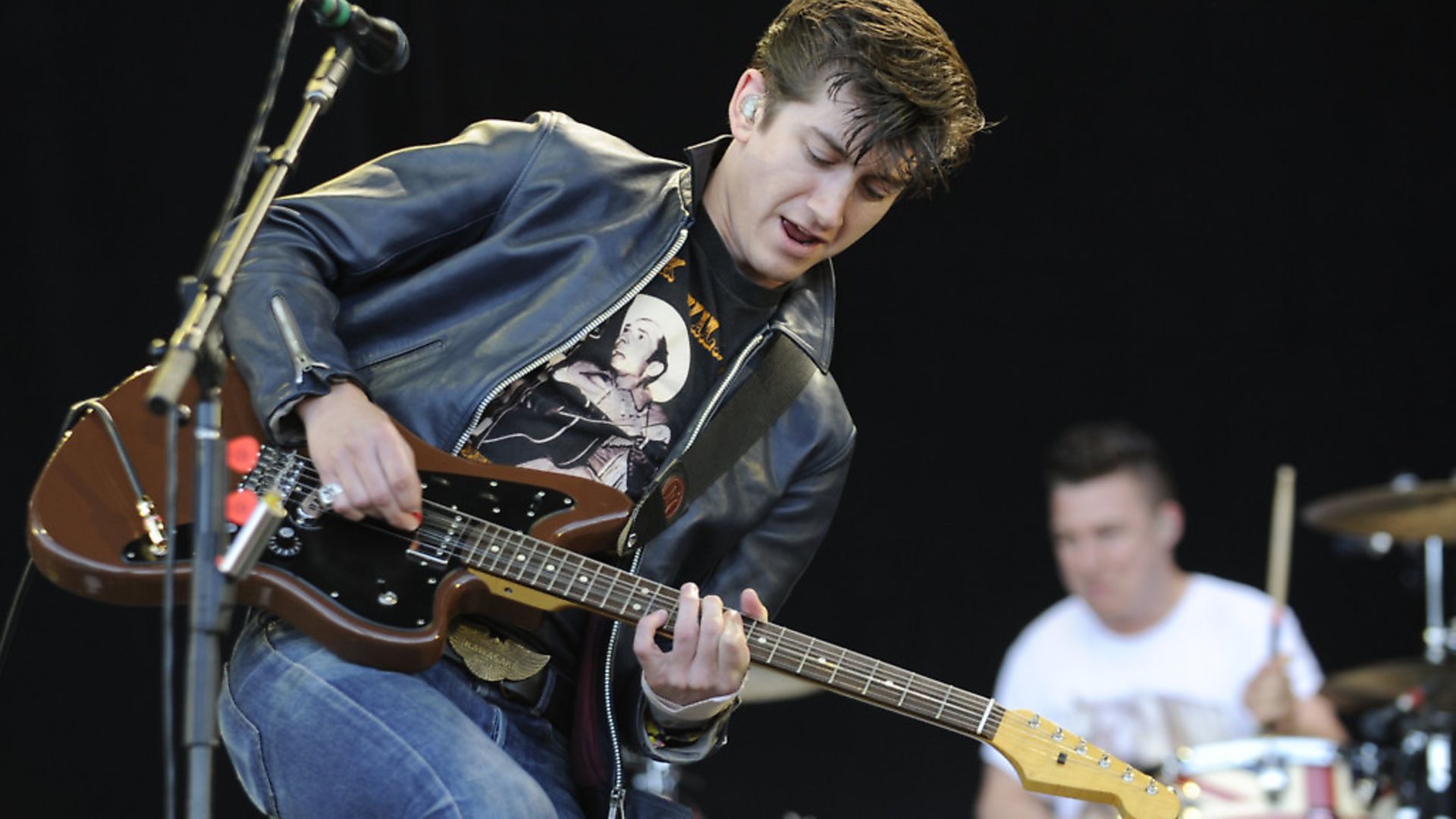

In the last 20 years, the civic pride of musicians from Sheffield has reached its zenith. Arctic Monkeys, who played their first gig at The Grapes pub on Trippet Lane, not far from the City Hall, in June 2003, have made their regional identity a key facet of their mystique, attacking bands who reject their roots on Fake Tales of San Francisco (“He talks of San Francisco/ He’s from Hunter’s Bar [a Sheffield suburb]/ I don’t quite know the distance/ But I’m sure that’s far”), and glorying in local dialect, from Mardy Bum to the spoken intro of The Ritz To The Rubble. Veteran Tony Christie covered these upstarts’ Only Ones Who Know on his 2008 album, Made In Sheffield, which was produced by Richard Hawley and also included Pulp and Human League covers – it was one of a number of collaborative projects between the city’s musicians in the last two decades.

In 1999, Christie provided the vocals for the Sheffield electronic trio All Seeing I’s infectious Walk Like A Panther (1999), with lyrics referencing the city written by Jarvis Cocker (“The old hometown just looks the same/ Like a derelict man who has died out of shame/ Like a jumble sale left out in the rain”) and a video filmed in its Castle Market. Christie’s LP Now’s The Time! (2011) was produced by Richard Barrett of All Seeing I, and included Cocker’s Get Christie and the retro-soul 7 Hills, a duet with Róisín Murphy of Sheffield-based dance act Moloko, whose Sing It Back and The Time Is Now were international hits at the turn of the millennium. Further Sheffield incestuousness has come via All Seeing I’s single 1st Man In Space (1999), featuring vocals from Phil Oakey and more lyrics from Cocker, while Richard Barratt of the trio had already collaborated with Richard H. Kirk of Cabaret Voltaire as Sweet Exorcist. If Sheffield has been a city that’s faced adversity, this has also instilled a strong sense of place and solidarity in its artists and, as such, it turns out to be a place that is inescapable.