As Simon & Garfunkel’s classic turns 50, ADAM BEHR considers the album’s political message and poignant personal relationship at its heart.

When the rock critic Robert Christgau first reviewed Simon and Garfunkel’s album Bridge over Troubled Water, released at the end of January 1970, his response was a notoriously terse one word: “Melodic.”

That’s true enough, although he wasn’t alone in his ambivalence. He gave the record a ‘B’ grade, and it received decidedly mixed reviews from fellow critics when it first appeared.

The public thought otherwise, however. It has since sold more than 25 million copies and was at the time a record-breaking hit, topping the charts internationally and becoming the UK’s best-selling album of the 1970s.

Critical assessments and sales figures are each, though not necessarily contradictory, inefficient measures in themselves of longer-term cultural effects.

Some hit albums drive themselves into the popular consciousness through making an aesthetic and conceptual splash on arrival, marking a sea-change from what came before. Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, for instance. Others osmose into the musical bloodstream by way of evolutionary rather than obviously revolutionary developments, whose lasting impact beyond the charts is felt over time. Bridge over Troubled Water falls into the latter category.

If some of its sterner critics have found it overproduced – particularly in comparison to its sparser, crisper predecessor Bookends – it nevertheless helped to set the tone for the rich production aesthetic of major rock albums in the 1970s and beyond. Its easily palatable lushness belies the painstaking creative process of putting it together, in technical as well as musical terms.

The creative use of reverb, for instance, saw engineer Roy Halee, who co-produced the record with Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, go to painstaking lengths for highly specific sounds.

The single drumbeat on The Boxer was recorded in a spot outside the lift in the Columbia studio building on East 52nd Street. With guitars positioned among more than half a dozen microphones the record pushed the studio’s equipment to its limits, and Halee synched up its eight-track recorders to double their capacity for his needs.

Among the industry accolades for this was a Grammy Award for Best Engineered Recording, as well as for Album of the Year, the title track winning Song of the Year and Contemporary Song of the Year. Its celebrated piano part was recognised with an Instrumental Arrangement of the Year Grammy for Simon and pianist Larry Knechtel who, along with Hal Blaine on drums and Joe Osborn on bass, was part of the team of crack session musicians known as the Wrecking Crew whose work graced a slew of hits in the 1960s and 1970s.

Underpinning this, though, was the forward momentum of Simon’s song-writing, which was starting to push at the edges of the folk and pop idioms from which he emerged, yet without abandoning them.

Buoyed by the success of Bookends, and the single Mrs. Robinson from Mike Nichols’ generation gap film The Graduate, the duo felt liberated to expand, and had a financial cushion to do so.

As Simon would say, “our confidence level was… very high. And we thought, ‘Hey, why don’t we do that?’. If we think it’s a good idea, probably it is a good idea. It’s a certain freedom that you get when you’re, kind of, sitting on top of the world”.

The album saw the blending of musical ideas and instrumental palettes from outside what were then western popular musical norms into the duo’s core folk-rock sound. Simon pulled elements of reggae into Why Don’t You Write Me and wrote new lyrics to El Cóndor Pasa by Peruvian composer Daniel Alomia Robles, having heard a version of it by folk group Los Incas, who featured on the record.

It was a musical modus operandi that predated the label ‘world music’ by over a decade and despite leading to what Robles’ son would describe as a “friendly” lawsuit – Simon claimed to have understood from Los Incas that it was a traditional melody – would feature more heavily the songwriter’s subsequent solo work, notably Graceland in 1986.

Even in 1970, musical excursions like this weren’t entirely new. What distinguished them and helped to broaden mainstream pop’s musical language, was the smoothness with which they were integrated into the record’s overall sound, in contrast to previous such experiments by the likes of The Beatles and Rolling Stones’ deployment of the sitar, for instance, where there was a more strident overlay of something self-consciously ‘new’ or different onto the song.

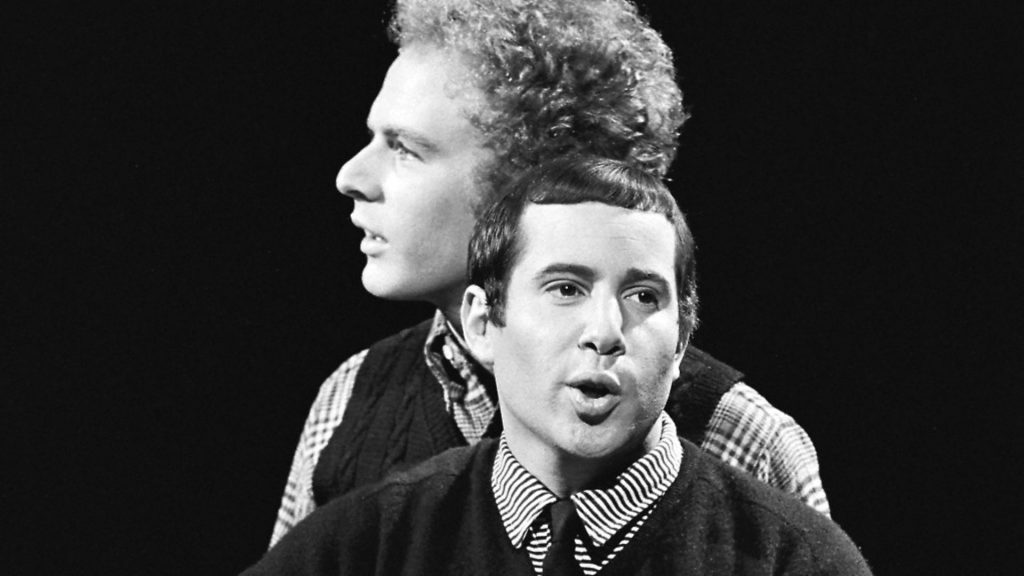

Still, even within more familiar territory, Simon’s increasing confidence was in evidence. Bridge over Troubled Water sits at a point where several traditions of American vernacular, and western classical, music cross-over through the combination of Simon’s ease with folk, pop and rock and roll, the choral purity of Garfunkel’s voice and the orchestral textures of arranger Ernie Freeman.

Many of the songs from the album have since become standards, and Bridge over Troubled Water itself provided an infusion of African American gospel music into folk rock, its turns of phrase entering the wider lexicon as a kind of modern, secular hymn. Simon himself felt it to be a step-change in his work, its deceptive simplicity providing a sense of universality: “I had no idea where it came from, one minute it wasn’t there, the next minute the whole line was there. It was one of the shocking moments in my songwriting career, and at the time I remember thinking, this is really considerably better than I usually write. But that’s how fast it came.”

As with the technical recording process, the seemingly effortless grace of the finished musical product belied the labour that went into it.

Simon and Knechtel worked for three days to transfer the song from guitar, on which it was originally written, to the piano. And as with the rest of the album, it was simultaneously the apex of individual craft and collaboration.

Originally a song with two verses, Garfunkel and Halee pressed Simon for a third which he wrote in the studio, adding the epic scale for which it has since become known.

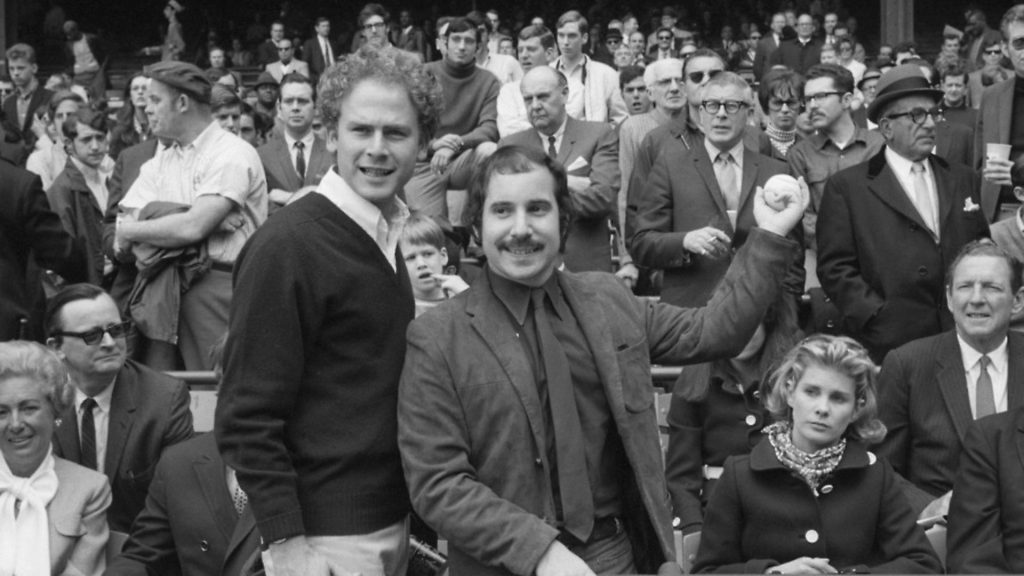

The song was also a locus for the brewing resentment and growing distance within the partnership that saw Simon and Garfunkel split at the peak of their recording career, having sung and recorded together since their school days.

When he sang it on his farewell tour of 2018, Simon talked of “reclaiming” it, and he has recalled sitting at the side of the stage brooding over the thunderous applause for early performances of it by Garfunkel thinking, “That’s my song”.

If Bridge over Troubled Water’ and The Boxer, which opened sides one and two of the record respectively, are the emotionally charged heavyweights and moments of grandeur, part of the album’s success was to maintain a surprising coherence across its tonal range, from the effervescent, percussive Cecilia to the plaintive, minimal Song for the Asking.

But the musical cohesiveness contained the seeds of dissolution. There have been plenty of records about faltering relationships, yet few where the break-up of an act is threaded through the material quite so significantly, even if this is more apparent with hindsight.

The songs masked commentary on the tensions between the singing partners that had been bubbling through their relationship since they were teenagers.

The Only Living Boy in New York was an address from Simon to Garfunkel, who was stuck in Mexico at the time filming Catch 22 for Nichols.

Simon’s part in the film had been dropped by Nichols, which didn’t help matters. “Tom, get your plane right on time,” he sings – Tom and Jerry being the name of their act as teenagers when they had a minor hit with Hey Schoolgirl.

The bossa nova-inflected So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright, ostensibly written for Garfunkel to sing as tribute to the architect he admired – Garfunkel had studied architecture during a post-school hiatus in their recording partnership – also presaged their split, with veiled references to their history together. Halee’s call “So long already Artie” echoes distantly over the fade out.

An immediate bone of contention amidst longer running interpersonal strains was what the 12th song should be. Garfunkel wanted a Bach-style chorale, which Simon rejected. For his part, Simon had written a rock and roll number about an aeroplane hijack called Cuba Si, Nixon No which Garfunkel couldn’t get behind.

The dispute summed up their divergent personal and musical paths and neither song made it onto the final release. “We argued about both of those songs and finally we said, look, forget it, that’s it, it’s done”, said Simon. “They were both indications of where we each wanted to go. I wanted to go more towards something rough and political and he wanted to go towards something classical.”

Simon’s music has tended to address politics implicitly rather than forthrightly. Ironically, on an occasion when he tackled the subject more directly two albums later on his solo song American Tune, a mournful rumination on the state of his country’s polity, he did so with a melody derived from Bach’s St Matthew Passion. Even so, the travails of Simon and Garfunkel’s personal politics on Bridge over Troubled Water did still echo a broader situation, with Simon’s compositions giving voice to a feeling of cultural unease and uncertainty at the turn of the decade.

The assassinations of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, along with Nixon’s victory in the 1968 election, permeated the album’s plangent tone – a valediction to the 1960s with a wary eye on the encroaching 1970s.

Indeed, in the lead up to its release, Simon and Garfunkel were featured in a documentary film Songs of America in November 1969 that starkly illustrated the divide in the nation.

The film, directed by Charles Grodin, drew attention to the discord. The first public broadcast of Bridge over Troubled Water was as part of a sequence that featured the funeral trains for the Kennedys and for Martin Luther King.

The sponsors of the show, AT&T, were furious and pulled out. Advertisers carpeted Grodin with harsh words about the programme’s “humanistic ideology” and warnings that sponsor affiliates in the southern states would emphatically not appreciate the depiction of black and white children attending school together.

A new sponsor stepped in – the Alberto Culver Company of the VO5 hair products – but the limits of Simon and Garfunkel’s anti-war, anti-segregationist social milieu were demonstrated when over a million viewers switched over after the first commercial break. The singers received hate mail and the show was pounded in the ratings by an ice-skating special on another channel.

Simon and Garfunkel’s music won out the following January, but their politics were in retreat. Indeed, their first reunion following Bridge over Troubled Water was at a benefit concert for senator George McGovern in 1972 as part of his presidential bid. Nixon beat McGovern in a landslide victory and although Watergate saw him depart office two years later, the moment the album spoke to – of accommodation between mass market appeal and the open worldview of, as Simon put it, “naïve kids from the northeast who thought that’s the way the word was” – had passed.

Bridge over Troubled Water marked the evolution of folk rock into an aspect of a broader mainstream, and the passage of Simon and Garfunkel to global record-breakers, although they would surf that wave as solo artists.

The schism in their working relationship, and friendship, had deeper roots than those manifested over the course of recording the album. Notwithstanding subsequent periodical reunions, until a final and apparently irrevocable collapse in 2010, the retrospective poignancy of a partnership coming apart at the peak of its creative prowess suffuses the songs, adding a note of personally expressed but universally felt ambivalence, leavened with a dose of possibility and exploration through their free movement across the musical landscape.

Then, as now, liberal sensibilities were beleaguered. A marker of personal and cultural loss for liberal America, but a commercial and aesthetic triumph, it has continued to resonate through its melodic mixture of weariness and hope – and its quiet but significant innovations.