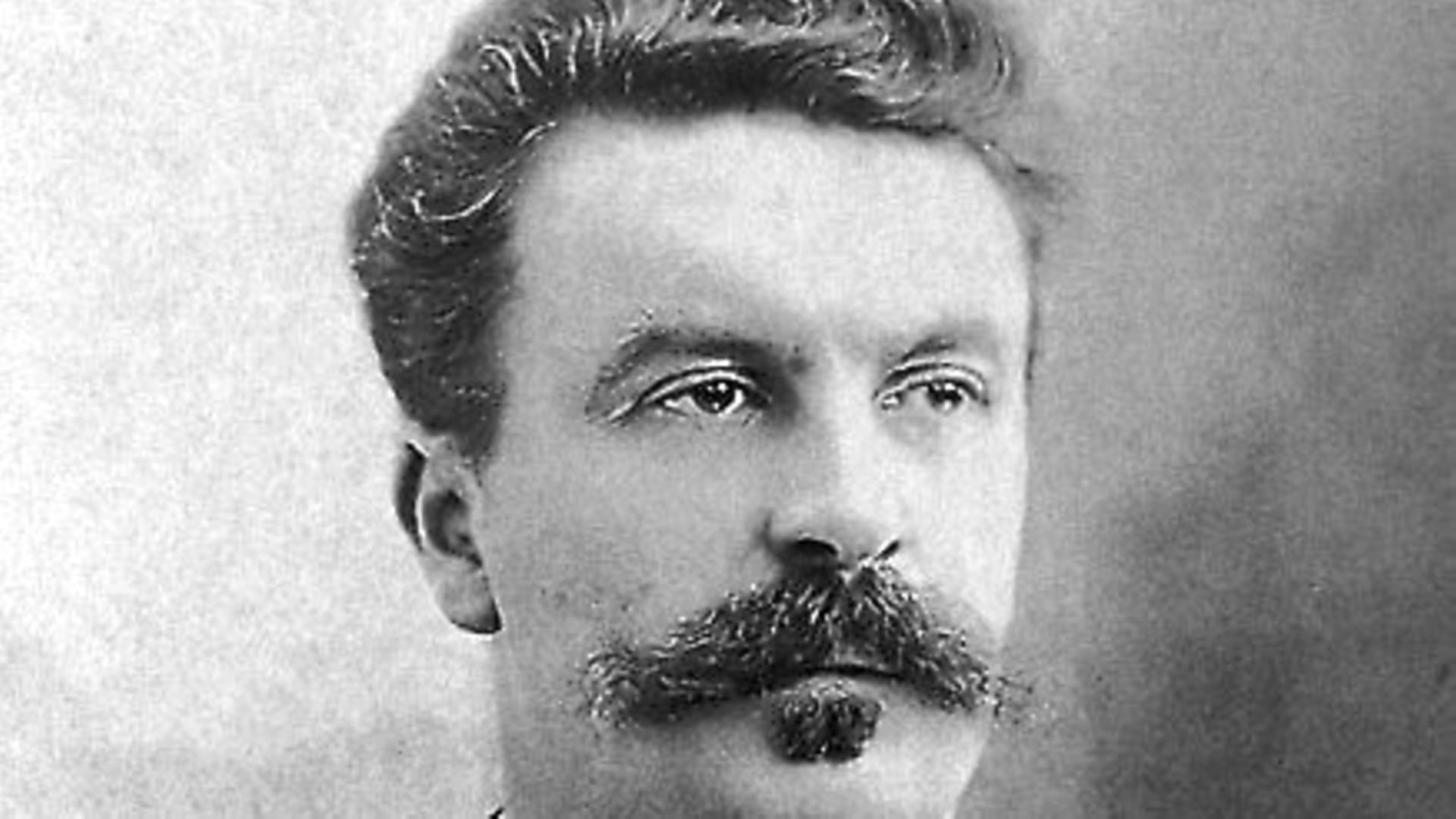

Guy de Maupassant was a giant of French literature who spanned genres. RICHARD LUCK concentrates on one of his most chilling tales

It won’t come as any great surprise to learn that William Shakespeare has had his work adapted on more occasions than any other writer. More of a shock is the identity of the runner-up in this particular category. Not Bram Stoker, not Conan Doyle, not Mary Shelley or Edgar Rice Burroughs or Jane Austen – no, the answer is a Frenchman whose short but remarkable life itself reads like fiction.

Henri René Albert Guy de Maupassant has provided the source material for a vast array of adaptations comprising everything from episodes of Star Trek and Tales of the Unexpected to cult horror movies such as Black Sabbath and Diary Of A Madman. The author of more than 300 short stories, de Maupassant has provided lazy screenwriters with no end of inspiration. And while we’ll be concentrating on his small but significant horror output, his stories, novels and plays spanned countless genres.

But first some background. Born in Tourville-sur-Arques in Normandy in 1850, de Maupassant’s interest in social standing – a feature of his naturalistic non-horror fiction – originated with his bourgeois parents who valued status to such an extent they petitioned to have ‘de’ added to the family name to suggest that were of noble bearing.

In reality, Gustave de Maupassant was a womanising bully who treated his wife so wretchedly, she bucked social convention and sought legal separation from her spouse.

Retaining custody of her sons Guy and Herve, Laure Le Poittevin proceeded to give her children an upbringing that emphasised the importance of enjoyment and education. By the time he was of school age, de Maupassant was exceptionally well-read and impossibly opinionated – such was the extent of his atheism, the 13-year-old Guy sought to have himself expelled from Rouen’s Institution Leroy-Petit. It was an act of rebellion that led to him meeting a key influence on his work, a friend of his mother’s whom Guy would spend a lot of time while his traditional education was on hold.

If you’re unfamiliar with de Maupassant’s work but recognise his name, it could be for a couple of reasons. The first is the story about how he liked to eat at the restaurant at the Eiffel Tour as that was the one place in Paris from which you couldn’t see the structure. The other might be due to his being long-time friends with Gustave Flaubert.

Though the Madame Bovary author first encountered de Maupassant while the latter was still a child. The pair then became better acquainted when Guy’s Franco-Prussian War service brought him to Paris. Needless to say, the military clerking gig de Maupassant landed lacked the glamour of liberating the besieged capital. On the other hand, had he taken up arms, it’s unlikely he’d have had the opportunity to befriend Ivan Turgenev, Emile Zola and the other great men of letters who regularly dined with Flaubert.

With these legends at his shoulder, de Maupassant quickly graduated from journalism to travel writing to penning short fiction. Adulation arrived with similar speed, with 1880’s Boule de Suif – a short story set during the Franco-Prussian conflict – celebrated wherever literature was held in high regard. Over the course of the next 11 years, de Maupassant wrote at least two short story collections each year, together with six novels including the best-sellers Une Vie and Bel Ami, plus Pierre et Jean, widely considered to be his most successful full-length fictional work.

But what of de Maupassant and the supernatural? In one sense, it was an aspect of his work from the outset. In 1875, he published The Flayed Hand under a pseudonym. A tale in which a madman’s severed mitt seeks vengeance, it’s been retold any number of times, most notably in Oliver Stone’s The Hand and the ‘Disembodied Hand’ sequence from Dr Terror’s House Of Horrors. Guy himself took another whack at it, publishing The Hand in 1883.

The author’s early work also included studies of fear such as The White Wolf and La Peur (both 1882), plus The Dead Girl (also 1882), a story in which the dead rise from the grave rather as they did in Edgar Allan Poe’s short fiction a half-century earlier. If de Maupassant’s early forays into horror fiction were formulaic and/or heavily influenced by the writing of others, come the mid-1880s, his supernatural fiction was in equal parts original and unsettling.

It was with the publication of The Horla in 1887 that it became clear de Maupassant was bent on exploring new territory. Also known as Modern Ghosts, the story centres on a middle-aged, middle-class man who becomes increasingly convinced that an external force is bent on his destruction. What’s more, the narrator believes that the spirit in question has come to France from the New World via a Brazilian ship. Shivers, anxiety, night terrors – the symptoms that overcome the protagonist aren’t unusual in themselves; rather it’s his conviction that the Horla (from the French hors, meaning ‘outside’, and la, ‘there’) is forever in his presence that is bizarre. With his unwanted but ill-defined visitor seemingly out to drive him mad, our hero finds himself unsure whether to destroy the Horla or end his life.

Although there is one reference to vampires in de Maupassant’s story, The Horla deals with a type of horror that would be completely unfamiliar to Bram Stoker. That the story’s biggest fans include HP Lovecraft gives a better indication of the kind of evil at its dark heart, an unnamed, external force not unlike Lovecraft’s unknowable elder gods. This is a threat that can be sensed rather than seen. And since it is largely indescribable, the victim has a hard time convincing those around him that it is an entity at all, but rather a malady of the mind.

Lovecraft wasn’t alone in admiring de Maupassant’s handiwork. In 1899, the poet William Hughes Means penned these lines:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there!

He wasn’t there again today,

Oh how I wish he’d go away.

It’s hard to think of a better – or briefer – summary of either The Horla or its power to disturb. Kind words also came de Maupassant’s way courtesy of that great man of American letters Mark Twain, while none other than Friedrich Nietzsche spoke well of the Frenchman in his autobiography.

Given his fascination with the human mind, it’s not so surprising that philosopher Nietzche should have been so interested in de Maupassant’s fiction. For at the core of The Horla lay something that had nothing to do with the supernatural and everything to do with the author’s mental health.

Quite when Guy de Maupassant contracted syphilis isn’t known. Since his brother also suffered from the disease, there’s even speculation that he had the condition from birth – lest we forget, the boys’ father was neither mentally stable nor especially faithful to their mother.

The symptoms of syphilis – alienation, paranoia, a constant sense of dread – are common to both the narrator of The Horla and its writer. In the years following the tale’s publication, de Maupassant wrote less and less and spent more and more time on his own. Come early 1892, his condition had deteriorated to such an extent that, while recuperating in Cannes, he tried to cut his own throat. In the wake of this unsuccessful suicide bid, de Maupassant’s family committed him to a Parisian mental asylum. It was there that he would die on July 6, 1893, a month short of his 43rd birthday.

“I have coveted everything and taken pleasure in nothing” – so reads the epitaph on his grave in Montparnasse Cemetery. What with his gifts as a writer of supernatural short fiction, the cruel might consider it fitting that de Maupassant lived so much of his life in hell.