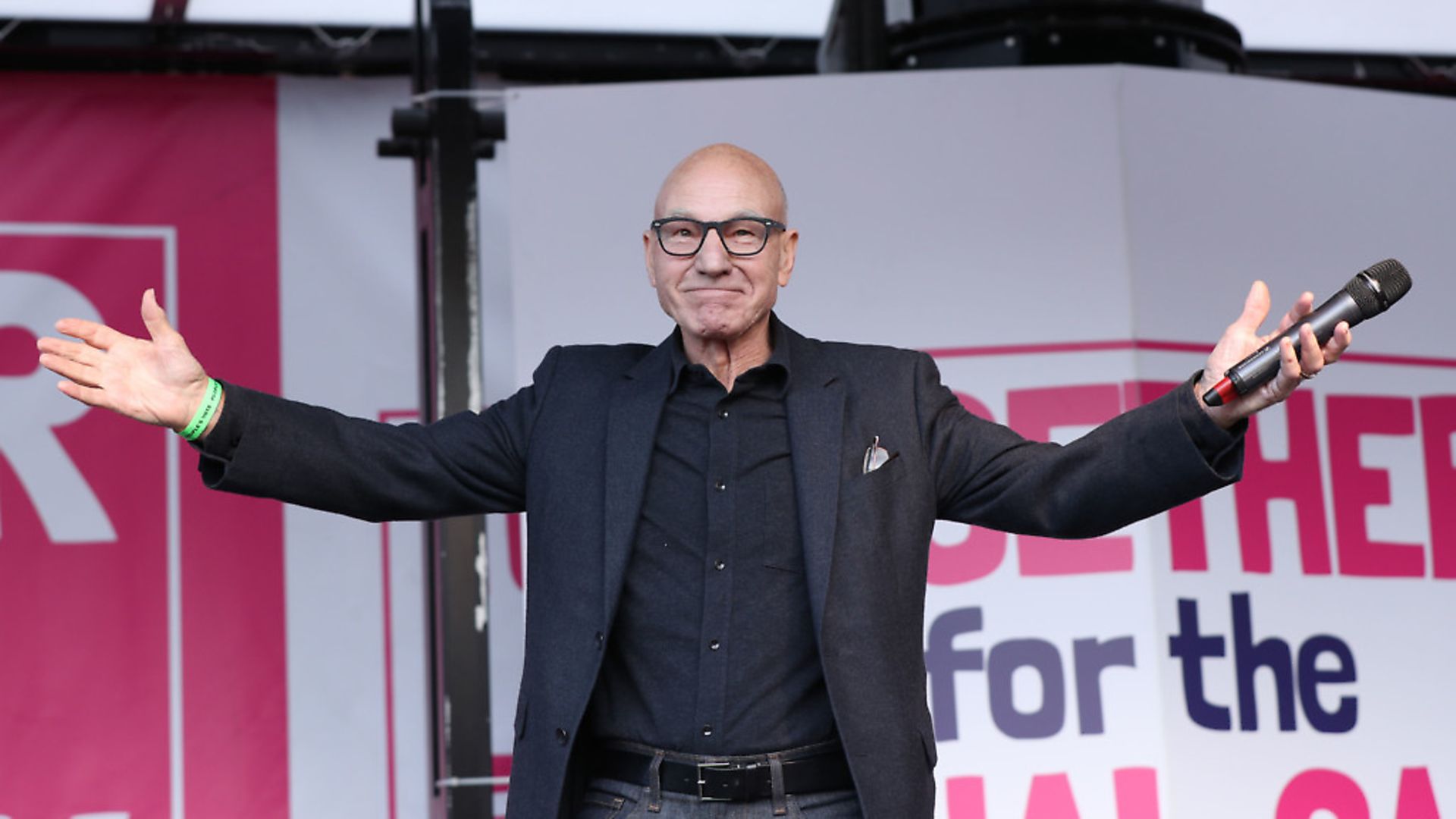

TIM WALKER talks to actor and campaigner Sir Patrick Stewart about politics, Star Trek and a very spiky encounter with the Labour leader

Ever since he first stood with a placard bearing the name of his local Labour candidate in Mirfield in the West Riding of Yorkshire in the 1945 general election – at the age of just five – Sir Patrick Stewart has been a steadfast and loyal member of the party.

The great actor duly spoke up for Jeremy Corbyn when he was elected leader and backed him at the last election, even if, in private, he was becoming, in common with a great many Labour members, frustrated and angry over his position on Brexit.

Still, Sir Patrick admits he was looking forward to seeing what Corbyn was like when, a few weeks ago, he got his first chance to meet him. He had hoped, even, to bend his ear on the issue he cares so much about. ‘He was talking to a group of my friends after a theatre performance and I wandered up to join them. Jeremy’s eye caught mine and he said ‘oh you’re looking very well’, and I made some light-hearted riposte along the lines of ‘you can’t judge a book by its cover’.

‘For some inexplicable reason, this annoyed him, and he shot back ‘you know, Patrick, you could just have said ‘thank you’ instead of making a joke out of it.’ I couldn’t understand how he could take offence at such an utterly innocuous remark, and no one else could, and it made for rather an awkward silence. I just thought ‘oh well, I tried’, and, after a suitable interval, I discreetly headed off home.’

The encounter symbolises the unhappy stage that Sir Patrick has come to in his relationship with a party that he has believed in passionately all his life. I ask him if he will be voting Labour again, and, after a long pause, he says, in a quiet and sad voice, probably not – so long as it supports Brexit and seems unable to deal swiftly and decisively with obvious evils such as anti-Semitism.

‘If I didn’t vote Labour, I would probably turn to the Green Party. I certainly agree with their positions on Brexit and climate change. To be perfectly honest, I find it difficult to understand what Labour really stands for or what it represents right now. It doesn’t feel like my party any more.

‘I am not a politician and I am not a strategist, but I have a suspicion Jeremy believes a disastrous Brexit would benefit him politically, and, in all the chaos and confusion that would occur after the policy is implemented – in either a hard or a soft way, I might add – he sees himself taking power. It seems to me to be just plain wrong to play with the country’s future in this way.

‘What Jeremy doesn’t appear to understand is that it would be the easiest thing in the world to attack the government on Brexit and to oppose it at every turn and to tear apart their arguments and expose it for what it is. There is, after all, nothing that is more opposed to basic Labour values than Brexit and I think just about everyone except him can now see that.’

In these unnervingly McCarthyite times, Sir Patrick has refused to be browbeaten into keeping his thoughts to himself on Brexit and this has resulted in him receiving online abuse – even threats of violence – and occasionally there have been confrontations in the street.

‘Friends of mine have asked me if it’s sensible to get into all of this publicly, but I am 78 now and I think a lot about the kind of world my children and grandchildren will be left with and it worries me.

‘I have had a chance to make something of my life and I want that for them, too. I am also a war baby – I was very aware, growing up, that families around me had lost people they loved and often depended upon in the war with Germany – and the EU always seemed to me to offer a way to ensure peace and stability in this increasingly uncertain world of ours. The EU is not perfect – I don’t pretend for one moment it is and it can be very annoying sometimes – but it seems to me it’s the least worst option we have, and, in terms of the things we don’t like about it, we should press hard to put them right.’

For all that he has achieved in his life, Sir Patrick is in person a humble, unassuming man and he strains throughout our conversation to make the point that he is talking not as a politician or an economist or whatever, but just as a private citizen who only went to a secondary modern school, but who happens nevertheless to care passionately about his country. He says that fundamentally his response to Brexit has been from the outset an emotional one.

It hurt him when he appeared on Andrew Marr’s show in the spring to launch the People’s Vote campaign and he found himself subjected to abuse of a kind that he had never received before from the right-wing press. He was portrayed as the privileged ‘Remainer luvvie’ who had jetted in from a film set in LA to tell us all how stupid we had been to vote to leave the EU.

He happens to be very much a Londoner and his background hardly fits in with that notion – Dad was a sergeant major in the Army and Mum worked in a textile mill and money was in short supply as he was growing up – but he knew only too well what was going on.

‘There is a new kind of anger and irrationality that Brexit has given expression to and it is worrying, but I will not be intimidated. I’ve had other issues I’ve cared about over the years – cannabis medicine, the right to die a dignified death, I’m a member of Amnesty International and I support Combat Stress, after seeing at first hand my father’s post-traumatic stress after the war – but I’ve never known a cause that it’s harder to have a practical and sensible conversation about than this one.

‘I wanted only to be as good an actor as I could be in my working life and I never set out to be a celebrity, but it came unexpectedly, relatively late after Star Trek: The Next Generation first aired, and I soon realised it brings with it certain responsibilities. I’ve talked to Ian McKellen and others about this, and, as pompous as this may sound, I think a lot of us in the entertainment business feel we should try to do what we can to make the world a better place.

‘Ian is a serious activist on gay rights and so many issues and I would never compare myself to him, but I do what I can. It startles me the influence that people like me can have on social media and so on. Of course, you can communicate, too, through the work you do and I have always been rather proud of the underlying social messaging going on with, say, Star Trek.

‘My character Jean-Luc Picard always stood for equality, democracy, fairness, and he had no interest in materialism and he hated prejudice. After the show’s creator Gene Roddenberry died – a man I loved dearly, but he was very much a Republican was Gene – we got even more of an opportunity when Rick Berman took over to discuss, in our own way, contemporary society in a the context of a show set in the future.’

Sir Patrick says he was struck by how many people said to him, after the surprise announcement this month that he would be reprising the role in a new CBS All Access series, how much Jean-Luc was ‘needed now more than ever’. He is inevitably no great fan of Donald Trump and what worries him about the phenomenon he represents in politics is that people will simply become accustomed to his offensiveness.

‘Repulsion and shock can only be sustained for a certain period of time and there is a real danger people will soon start to just shrug their shoulders when Trump starts to tell his lies or attack decent, innocent people, and say ‘oh well, that’s just him’, and he will get a second term.

‘We are getting used to this technique now in politics where a politician without any scruples says the great big lie or outrageous thing and it gets all the headlines, and then, if someone manages to prove it’s made up, there is maybe a retraction of some kind that goes in small type on an inside page and no one notices.

‘We are seeing this here, too. People said after Boris Johnson talked the other day about Muslim women ‘going around looking like letterboxes or bank robbers’. that he was just joking and it was only ‘Boris being Boris’, but no, actually, it was not alright. It was insulting and discriminating and anyone who knows anything about history knows where this can lead.’

If there is amorality to politics, there is, too, in the modern media and Sir Patrick is struck by the lack of restraint – if not simple good taste – in the reporting of incendiary comments of this kind. ‘Enoch Powell’s attempt to stir up racial hatred with the Rivers of Blood speech he made in 1968 caused a sensation at the time, but I don’t remember him being made into a media star in the years that followed. I’m sure he would have loved to have gone on television a lot, and get interviewed by the papers, but the requests weren’t forthcoming. Now it seems to be just about the ratings: the more outrageous you are, the more exposure you are accorded.’

Sir Patrick sees Brexit and Trump and the rise of maverick politicians around the world as the inevitable consequence of a divide that was allowed to open up between elected representatives and those who elected them. ‘There were people who saw this sense of alienation and exploited it and we have now this politics of selfishness – where it’s all about this idea we are taking care of ourselves and to hell with everyone else – but we have so many issues now that are confronting us, such as automation, and, even more importantly, climate change, that we have to work out how to tackle together. This is no time for isolationism.

‘I have nightmarish visions, of course, about where we are headed now – it can only really take us to a place where the very rich withdraw behind security gates and barbed wire fences and we give up on the idea of the kind of community I’ve known all my life – but I am not reconciled to this in any way at all. I sense more and more we are seeing this and recoiling from it.

‘I got involved in the People’s Vote campaign because it is quite a modest and very democratic proposal it’s putting forward – it wants simply a public vote on the final Brexit deal between the UK and European Union – and, you know, if we get this, and people vote for this deal, Remainers like me will settle back and say ‘That’s fine, this has been done properly. We have made the decision now in full possession of the facts and fully aware of the consequences’.

‘We couldn’t, of course, say that about the EU referendum when we had been made outrageous promises such as the £350 million a week for the NHS and so many other untruths were told. This is why we have to have a chance to make a decision on the facts, not the fantasies.’

Sir Patrick has always been at heart an optimist, and, while he knows a lot of damage has already been done to Britain by the Brexiteers, he has no doubt we will get through this.

‘I think we will come out of this experience a lot stronger. We have all of us learnt from it. I think it will make us appreciate basic freedoms and rights that in the past perhaps we took too much for granted. I think we will look back on it as a turning point in our history.’