In 1844 Strauss Senior, the first pop idol, soon found himself eclipsed by something rawer, says SOPHIA DEBOICK.

The year 1844 was one of mixed fortunes for musical stars both old and new, as the second wave of Romantic composers began to emerge. The perpetually sickly Chopin was seriously ailing for the first half of the year, but rallied to finalise his delicate Berceuse in D Flat Major, highly technical Sonata in B Minor and three mazurkas, based on the traditional dance of his Polish homeland.

Exact contemporary Schumann was also managing to be productive, busy touring Russia and writing his setting for Faust, despite already experiencing major symptoms of his final decline into syphilitic madness. Verdi was just 30 and still in the process of establishing himself. His Ernani, based on the Victor Hugo play, was a welcome success when it was premiered in Venice in March after several career setbacks.

Meanwhile, Berlioz published his influential technical study of the orchestra and its instruments, Traite di l’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes, a manual for many future classical greats. But it was a watershed year for Mendelssohn and Strauss in particular, and while Liszt was the focus of the secular cult that was in full swing, religious fervour simmered and then boiled over elsewhere, proving undimmed by the march of progress in both technology and society in a period of bewildering change.

Having become director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra almost a decade earlier, and founded the Leipzig Conservatory just the year before, Mendelssohn directed much of his energy in this year towards the development of the musical life of that city. But that summer he made his eighth visit to Britain, conducting five of the last eight concerts of the London Philharmonic Society and consolidating his position as one of the country’s best-loved musical figures.

Queen Victoria herself attended his June 10 performance and was already a personal friend to whom he had dedicated his ‘Scottish’ Symphony of two years before. The year also saw his final major orchestral work, Violin Concerto in E Minor.

It would be highly influential in its iconoclastic inventiveness, ditching a long orchestral introduction in favour of the immediacy of the soloist playing from the very beginning of the piece. Leading violinist of the century, Joseph Joachim, who had made his London debut aged only 12 with Mendelssohn conducting during the Philharmonic concerts that May, would later say that of the great German violin concertos, Mendelssohn’s 1844 piece was ‘the most inward, the heart’s jewel’.

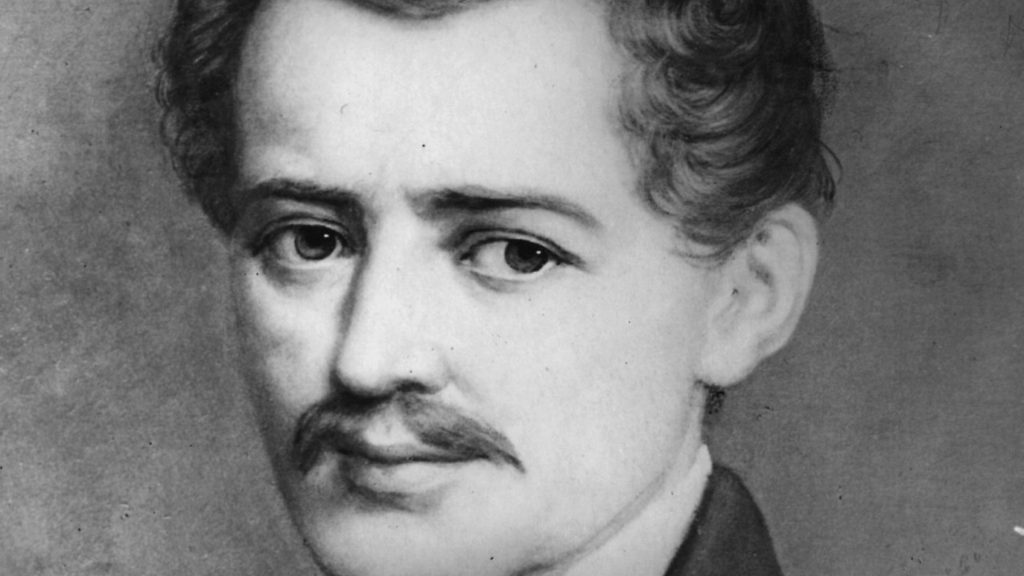

Although not quite as young as fellow violinist Joachim, Johann Strauss the Younger was but a tender 18 years old when he made his debut at Dommayer’s Casino in the upmarket Vienna suburb of Hietzing in mid-October, introducing him to Viennese society and its flourishing musical world.

His Herzenslust (‘Heart’s Content’) polka, waltzes Sinngedichte (‘Poems of the Senses’) and Gunstwerber (‘Wooers of Favour’), and the Debut-Quadrille were all composed that autumn specially for the performance. Strauss Senior, still aged only 40, was one of the most celebrated conductors and composers not only in Vienna, but the whole European musical scene of which that city was the beating heart, and the performance marked not only the younger Strauss’ emergence from his father’s shadow but his defiance of his disapproval of him following the musical path (he had beaten him as a child when he discovered he was secretly taking violin lessons).

Strauss Senior blacklisted the Dommayer from then on, and a professional rivalry was added to the friction between father and the son he had abandoned when he left his family for his mistress. As Strauss II composed era-defining pieces and presided over the typical salon orchestras of the day, he became the dance king of Romanticism, even though he admitted to being a terrible dancer himself, saying ‘I have to give a firm ‘no’ to the many tempting and alluring invitations to the dance’.

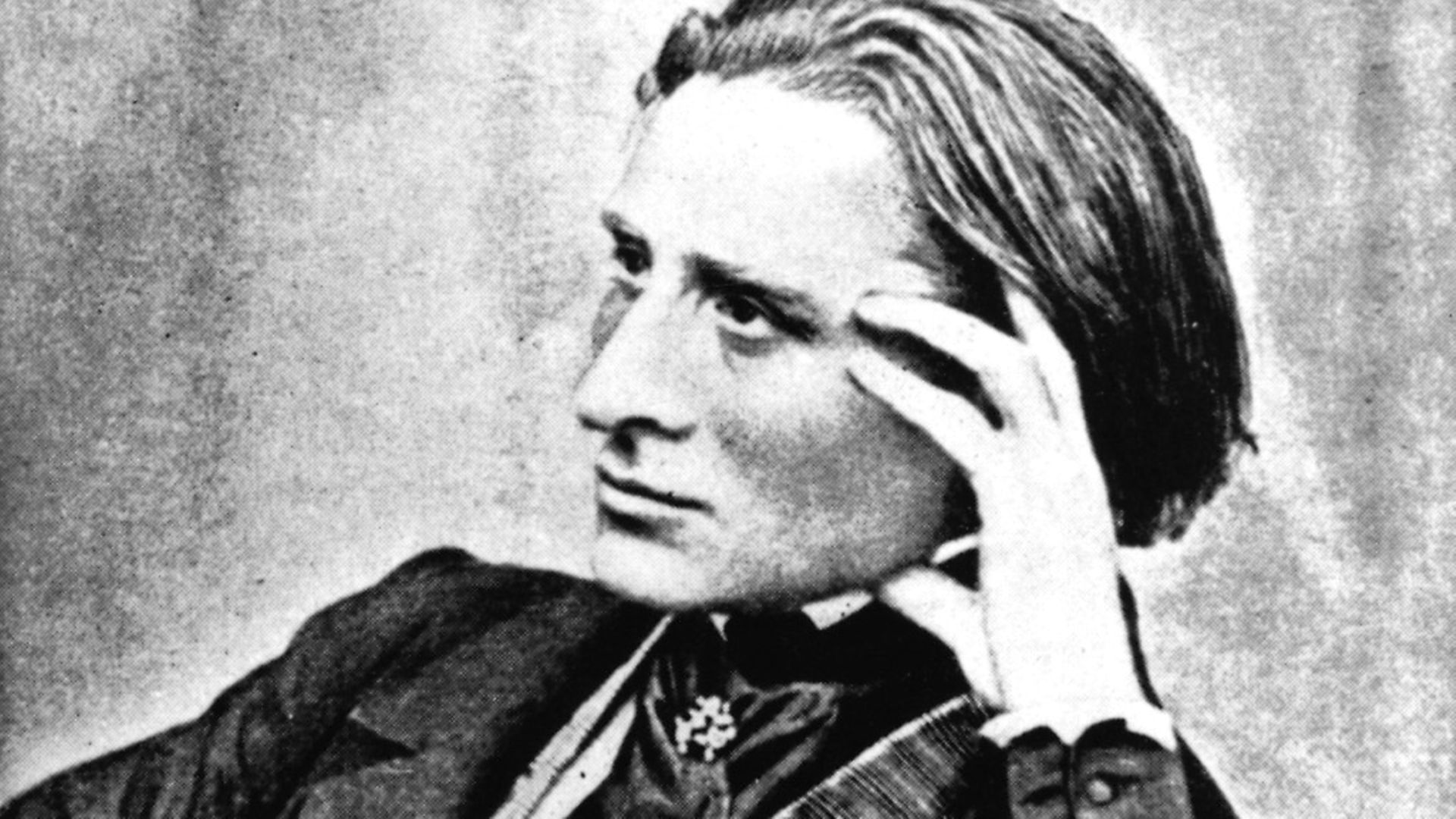

Strauss Senior has been credited by some with being the first pop idol, astutely promoting himself via many tours with his own dance orchestra, and making the waltz into the beginnings of a dance craze. But his popularity was nothing compared to that of Liszt, widely referred to as the first rock star, and at the peak of his career as a touring pianist in 1844.

His energetic, dramatic style of performance, uniquely playing from memory instead of taking a score onstage so as not to impede his dynamism, along with his good looks made him a truly magnetic personality.

The earliest known photograph of him, taken in 1843, shows an aquiline nose, devastating cheekbones and a crop of dark, floppy hair – every inch the alleged lothario who had liaisons with noblewomen across Europe. On stage, Liszt elicited hysterical reactions from his audience of a type never seen before, and it foreshadowed the 20th century pop cult in its emphasis on merch and mementoes, as Liszt brooches became the in thing and fans clamoured for broken piano strings, locks of hair or gloves in a quasi-religious coveting of relics.

While 1844 was significant for Liszt in several ways – he separated from the Countess Marie d’Agoult, the mother of his three illegitimate children, in spring, and began a ground-breaking tour of Spain in October – the coining of the term ‘Lisztomania’ by poet Heinrich Heine in April made it a year that guaranteed the composer’s legendary status.

Writing about the Paris concert season that had just finished, Heine’s flood of tongue-in-cheek-tinged hyperbole designated Liszt ‘the modern Homer, whom all Germany, Hungary, and France, the three greatest countries, claim as their native child, while only seven small provincial towns contended for the singer of The Iliad!’. He went on about ‘how powerful, how startling was the effect of his mere appearance! How vehement was the applause which greeted him! A delirium unparalleled in the annals of furore!’, speculating that the cause of this was perhaps ‘the electric action of a demonic nature on a closely pressed multitude, the contagious power of the ecstasy, and perhaps a magnetism in music itself, which is a spiritual malady which vibrates in most of us’.

Indeed, while Heine’s use of the suffix ‘mania’ was very much of the time, indicating how the clamour around Liszt was discussed as if it was an actual medical affliction or contagion, his description of the elusive and indescribable pull of celebrity and power of music still resonates today.

The cultural innovation of celebrity was joined by social and technological inventiveness, although change and ‘progress’ rarely benefited everybody. The year’s inventions included Gustaf Erik Pasch’s safety match and Charles Goodyear’s vulcanized rubber, making car tyres possible, while the November birth of Karl Benz, patentee of the first petrol-powered car, was also pivotal for the coming motoring age.

Meanwhile, Samuel Morse was sending the first electrical telegram and the content of that first message, taken from Numbers 23:23 – ‘What hath God wrought?’ – seemed appropriate to an era of awe-inspiring progress.

Meanwhile, in the age of Dickens, Britain was getting a social conscience, and the April closure of London’s Fleet debtor’s prison was followed two months later by the founding of the Young Men’s Christian Association to provide physically and morally salubrious accommodation for the single men who came to the cities to look for work, but often found only squalor and threats to their virtue.

The modern co-operative movement was born when the Rochdale Pioneers, a group of textile mill workers, laid down principles of shared ownership and opened a shop to serve their community, impoverished by the impact of the Industrial Revolution on their jobs.

In September, Friedrich Engels began writing his The Condition of the Working Class in England, drawing on time spent working in Manchester since 1842, and vividly documented how industrialisation had left those on society’s margins in a worse position than ever.

But if it seemed to be a time of disenchantment and modernisation at any cost, this was belied by a flare-up of atavistic religious fervour that made Lisztomania look tame.

On June 27, founder of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, was shot dead by a marauding mob following a split in his church, associated civil unrest, and Smith being held on treason charges. Despite Smith being condemned in the same tones as a modern cult leader at the time, Brigham Young swiftly took up the reins and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would go on to become the fourth-largest Christian denomination in the United States. Neither did the white heat of the events of 1844 consume the Millerites. Baptist lay preacher William Miller had built a national movement in a little over a decade and then ramped up expectation of the Second Coming on his appointed date of October 22, 1844. When the date passed uneventfully it was christened the Great Disappointment, but the Seventh-day Adventist Church survived to become a major global faith with as many as 20 million members.

Such religious feverishness was not an American preserve, neither was it found only in new, fringe faiths as, situated between the appearance of the Virgin Mary to Saint Catherine Labouré in Paris in 1830 and the 1846 visions at La Salette, southeastern France, of a sorrowful Virgin predicting the apocalypse, 1844 found Catholic Europe too experiencing the paranoia that is a common reaction to the disorientation of quickly changing times.

Before the 1840s had ended the rampant flowering of Romantic music would be dealt a blow by some of its greatest luminaries bowing out. Mendelssohn and Chopin died, aged only in their late 30s, along with Strauss Senior, aged not much more, before the decade was over. The Year of Revolution, 1848, was in touching distance, and would rock European society, with uprisings in March and October of that year seeing blood spilled on the streets of Vienna itself.

Warring allegiances were sparked even between members of the same family, and while Strauss Senior wrote his much-loved clap-along favourite the Radetzky-Marsch to celebrate the victory of Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz at the Battle of Custoza, the final crushing of the Sardinian rebellion against the Austrian Empire, Strauss Junior again defied his father to side with the revolutionaries.

For all of 1844’s social, technological, religious and cultural upheaval, even more seismically disruptive times were just around the corner.