Phil Spector was responsible for one of the greatest Christmas records ever made. SOPHIA DEBOICK tells the story and asks if we must reassess it in the light of his later murder conviction.

He was the one producer deserving of the overused term ‘genius’, but Phil Spector will spend Christmas – and his 80th birthday on Boxing Day – in a California prison for the murder of Lana Clarkson.

In early 2003 Spector shot the 40-year-old actress and model in the face at his Alhambra mansion hours after meeting her. His history of often alcohol-fuelled violence and coercion was already well-known.

His first wife, Annette Merar, spoke of relentless verbal abuse, while second wife Ronnie Bennett of Spector’s model girl group The Ronettes revealed how he sabotaged her career, kept her a virtual prisoner and repeatedly threatened to kill her after their 1968 marriage. Spector’s three adoptive sons have accused him of both abuse and neglect.

Professionally, Spector’s reputation was no better. Singer Darlene Love would recount how he released her recordings without proper credit and vindictively exploited a clause in her original contract to ‘buy’ her back and derail her attempts to re-establish her career.

In the studio, Spector was often controlling and unhinged – Leonard Cohen, who recorded with him in 1977, called the atmosphere around him ‘Hitlerian’ – and he was known to pull a gun at work just as Ronnie said he frequently did at home.

Several women would testify to having been threatened in such a way during the Clarkson murder trial.

Yet, Spector was the man responsible for some of the sweetest, most intensely romantic and joyful pop records ever made. And despite having produced albums for the greatest names in pop history – the Beatles, as well as John Lennon’s solo work – he considered his 1963 album of sugary Christmas songs, A Christmas Gift for You, one of the most important projects of his whole career.

Spector might have been accused of having delusions of grandeur, always being convinced of his own genius, but the sound he created achieved genuine grandeur and captured timeless emotions.

Spector was born in the Bronx to a Ukrainian Jewish family whose tragedies and quiet resentments contributed to fashioning Spector into an alienated and damaged personality. A short and sickly child, Spector was just nine years old when his father killed himself.

Shortly afterwards, he moved with his overbearing mother and unstable teenage sister to the West Coast, where the carefree Californian beach life couldn’t have been a worse fit with his introspective personality. He was chronically socially awkward and a natural draw to bullies.

Even so, it was in California that Spector formed his first band, the Teddy Bears. They landed a record deal with a small independent label and, miraculously, the song Spector had written and produced, To Know Him Is To Love Him (a sentiment adapted from his father’s headstone epitaph), topped the US charts in 1958.

This first taste of success was a vindication for Spector, the eternal outsider, and he developed an appetite for that sense of winning. Following an apprenticeship with Hound Dog writers Leiber and Stoller, he founded his own label, Philles Records, in 1961. The pursuit of each hit would be an attempt to exact some kind of revenge on a world that had never shown him much kindness.

Spector emerged in the early 1960s as pop’s first truly visionary producer. His perfectionism meant gruelling hours in the studio obsessively finessing his sound and demanding endless retakes from his artists. The result was that the teen pop song was suddenly painted on an epic canvas.

Spector’s lush ‘Wall of Sound’ was less a mere characteristic style than a whole new pop idiom, one that would later be adopted by Berry Gordy and Brian Wilson, among many others. After signing The Crystals and The Ronettes, Darlene Love of the Blossoms, and Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans to his label and establishing a crack crew of session musicians who came to be dubbed the ‘Wrecking Crew’, between 1961 and 1966 he ruled pop, capturing the adolescent tension between innocence and sexual awakening just as the teenager was enjoying its cultural moment. Spector – only just out of his teenage years himself – was young enough to truly understand the emotions at hand.

The Crystals’ No.1, He’s a Rebel of late 1962 (in fact, sung by the Blossoms but credited to the other girl group by Spector) was a foreshadowing of the successes of 1963. The exuberance of Da Doo Ron Ron by The Crystals – a No.3 in June 1963 and an example of immortal pop genius – and the sheer yearning of The Ronettes’ Be My Baby, which reached No.2 in the autumn, made 1963 his year.

That summer he began working on a very personal album – a collection of the heartwarming festive standards of the 1930s, 40s and 50s that Spector loved, recorded by his Philles artists.

Like many robbed of their childhood, Christmas was of deep importance to Spector and he took what might have seemed like a corny covers album deadly seriously.

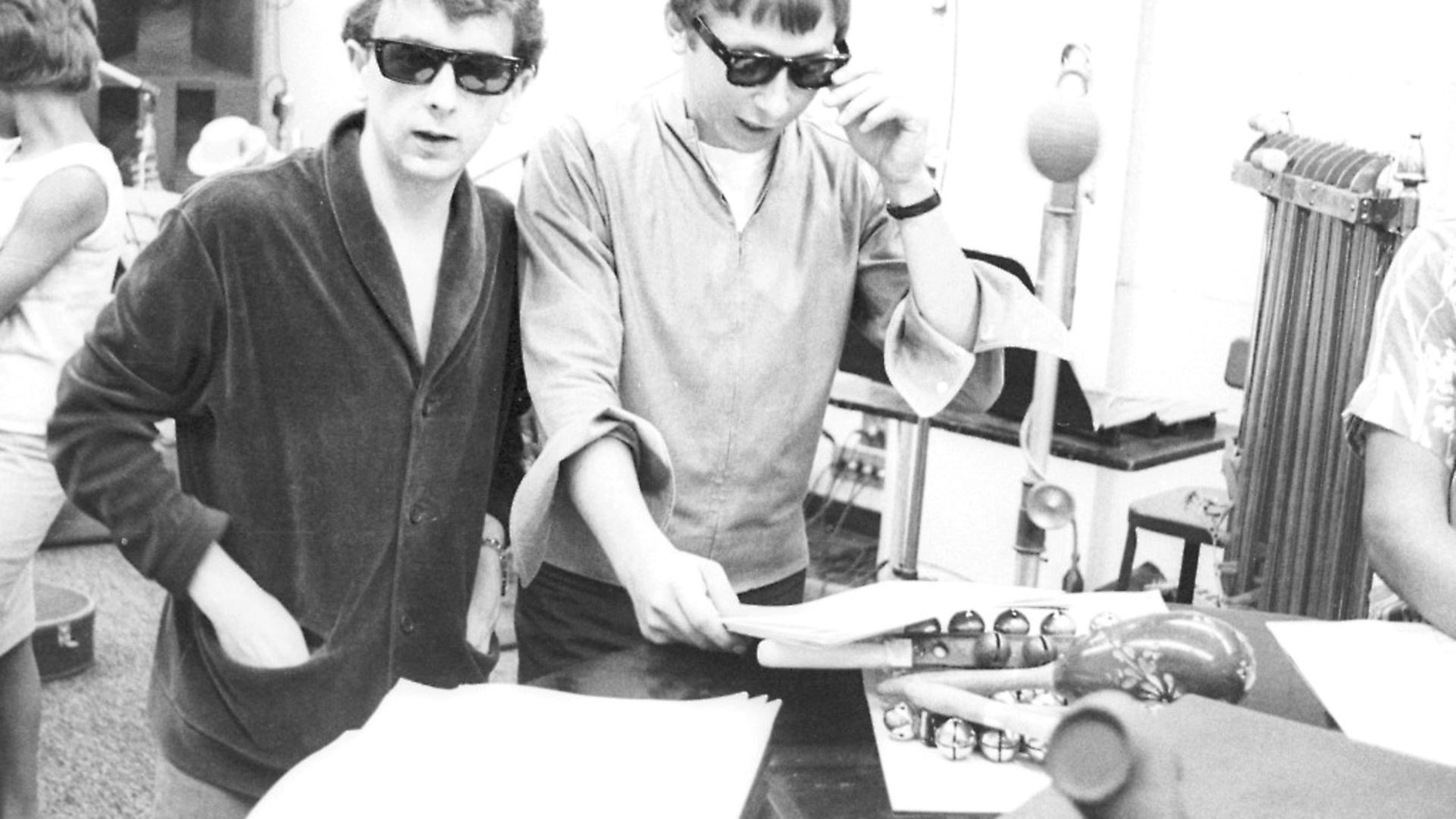

Spector’s obsessive determination to make the album a success meant that his artists hardly found a Christmassy atmosphere of bonhomie when they arrived at LA’s Gold Star Studios to begin work on A Christmas Gift for You. For six solid weeks that summer Spector worked on the record near-continuously and expected his artists to do the same.

The studios had been booked 24 hours a day and camp beds were set up on the studio floor. The summer heat was sweltering, there was no air conditioning, and Spector’s use of several players of the same instrument to build his huge sound meant the studios were packed with people, making the atmosphere even more claustrophobic.

Some soon to be famous faces were involved, but didn’t necessarily enjoy the experience. Brian Wilson, who had just had a major hit that May with Surfin’ U.S.A, dropped into the studio but buckled under his idol’s gaze when Spector invited him to play piano on the album.

Sonny Bono and a 17-year-old Cher, both of whom had sung backing vocals for Spector on Da Doo Ron Ron and Be My Baby, contributed their voices again, although Bono would later describe his role in the Spector organisation as “a general flunky for Phillip”.

In interviews for Mick Brown’s definitive Spector biography, Tearing Down the Wall of Sound (2007), some of the key personnel on A Christmas Gift for You vividly recalled the extremes Spector pushed them to.

While The Ronettes’ Nedra Talley recalled a sense of camaraderie among the Philles artists, she also spoke of how they were so sleep deprived they became delirious. Spector’s engineer, Larry Levine, who had been his right-hand man in creating the Wall of Sound, found the sessions “physically excruciating”, adding “my nerves were shattered”.

It was the final straw – he told Spector he never wanted to work with him again. Jeff Barry, who wrote many of the Spector stable’s hits with his wife Ellie Greenwich, later recalled with bewilderment: “I stood there for days and days and days, just playing shakers.”

But the fraught circumstances of the LP’s production didn’t register on what was a jubilant record where Jack Nitzsche’s arrangements were the star just as much as Spector’s sound.

The Barry-Greenwich-Spector penned Christmas (Baby Please Come Home) was the album’s only original song. With a career-defining vocal performance from Darlene Love, it built to a goosebump-inducing crescendo of piano-laden emotion and was head and shoulders above the rest of the album.

Love’s White Christmas, which opened the record, included an introspective spoken variation on Irving Berlin’s original, rarely-heard lyrics: “The sun is shining, the grass is green/ The orange and palm trees sway/ There’s never been such a day/ In old LA/ But it’s December the 24th/ And I’m longing to be up north/ So I can have my very own white Christmas.”

That was a fair reflection of the landscape in which the record was made, yet her Marshmallow World and Winter Wonderland still managed to be convincing in their imagery of a magically sparkling, snowy landscape.

Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans (Bobby Sheen with backing from Darlene Love and fellow Blossoms member Fanita James), took The Bells of St. Mary’s, a song popularised by Bing Crosby in the 1940s, and turned it into a soul ballad, Sheen giving it every ounce of earnestness.

Their version of Gene Autry’s Here Comes Santa Claus was more upbeat, as Love and James chirruped “Santa Claus is coming tonight!”.

Despite The Crystals appearing on the cover of the record, only LaLa Brooks of the group actually sang on it. While her versions of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and Parade of the Wooden Soldiers were rather plodding affairs, Santa Claus Is Coming to Town was a riot. Beginning with Brahms’ Berceuse under a gently spoken part (“Now Santa is a busy man, he has no time for play/ He’s got millions of stockings to fill on Christmas day”), it suddenly stormed into a near delirious, sax-heavy, rollicking version of the song.

The Ronettes’ three tracks were the record’s best moments aside from Christmas (Baby Please Come Home). They had big band touches that honoured the pedigree of the songs and pleasingly kitsch sound effects: Clip-clopping hooves, a braying horse and, of course, sleigh bells, on Sleigh Ride; a big smacking kiss at the beginning of I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus.

Ronnie Spector’s naive, bubblegum vocals on the latter, as well as on Frosty the Snowman, both of which were sung from the point of view of a child, made them near novelty songs.

Spector had always said his records were “little symphonies for kids”. With A Christmas Gift for You that vision was fully realised.

The Ronettes’ insistent “Ring-a-ling-a-ling ding-dong-ding” throughout Sleigh Ride was ready made for the playground, but all this was knowing enough to be appealing to adults too, and the overall result was the most good-natured, warm and celebratory record imaginable.

But A Christmas Gift for You was a victim of events. As the copies were being shipped for release, president Kennedy was shot. America faced a Christmas in mourning and Spector pulled the record.

Only latterly was it rediscovered as a yuletide classic, the Wall of Sound becoming synonymous with Christmas for many.

Spector was crushed by the failure of the album, recalling to Mick Brown nearly 40 years later: “That was devastating to me.”

In his spoken remarks over the closing track of the album, Silent Night, Spector had told his public: “The biggest thanks goes to you for giving me the opportunity to relate my feelings of Christmas through the music that I love.” Perhaps, for once, he was sincere.

Spector’s moment in the sun was in fact largely over anyway. When the Beatles arrived in the US on a Pan Am flight from London in February 1964 everything changed (ironically, Spector was on that very same flight).

A switch to the more complex and adult emotion of the Righteous Brothers’ You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’ (1964) gave Spector another US No.1, but his intense teenage pop had been killed by the guitar and the English accent.

The failure of Ike and Tina Turner’s River Deep – Mountain High (1966) – a record Spector had considered the absolute apotheosis of his sound, but that only reached a humiliating No.88 on the Billboard Hot 100 – wounded him deeply.

Still under 30, he largely retired, occasionally re-emerging to work with artists he was particularly enthusiastic about. Slowly, Spector became better known as a byword for eccentricity than for musical genius.

Spector was convicted of the second degree murder of Lana Clarkson in 2009 and sentenced to 19 years to life. As with the case of Michael Jackson, some have asked if it is right to still listen to Spector’s music since it was the wholesale vision of a man now known to have committed monstrous acts.

He destroyed lives. He was also a man whose own losses, from the suicide of his father in 1949 to the death of his nine-year-old son Phil Jnr. from leukaemia on Christmas Day 1991, destroyed his own life.

He sought professional help for the “devils inside”, as he put it, over many decades, to little avail. While many friends spoke warmly of him, claiming to know a “different Phil”, his cruelty and violence was a fact. But in his music there are the best of human emotions – joy, wonder, love.

A Christmas Gift for You was his most sustained expression of those sentiments, and the swells of emotion in Spector’s sound were surely not possible if he didn’t feel them himself. The album has a more profound meaning than simple festive celebration – it is evidence of the tenacity of the good in the human spirit, even in the most lost.