Fifty years ago, with the Space Race still in the balance, a late twist gave the Soviets a shot at victory. MICK O’HARE looks back at a near miss, and considers what might have been

‘We’re burning up…’

The audio from the capsule of Apollo 1 makes for grim listening. In a matter of seconds on the afternoon of January 27, 1967, fire claimed the lives of astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee as they sat atop their Saturn IB rocket during a routine test. When sparks from a faulty wire ignited the pure oxygen environment of their capsule they had no chance. It was the first tragedy of the American space programme and put a severe dent in NASA’s ambitions to put a man on the Moon before the end of the decade.

Flights were suspended for 20 months while NASA administrator James Webb put his career on the line to save the Apollo programme in the face of congressional and, crucially, public concerns. Ultimately he carried the can, but Apollo was restarted. Yet as the United States’ will faltered, its great rival for space dominance, the Soviet Union, sniffed an opportunity to beat the Americans to the Moon.

In the early 1960s the USSR had led the race into space, putting the first satellite, Sputnik I, and the first man, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit. But by 1967 the wealth and sophistication of NASA had put the USA firmly on the front foot. Apollo 1 changed all that. The Soviets spotted an opening, but they too were hamstrung: they would have to launch their moonshot without their talisman, Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.

Korolev was the designer, engineer, strategist and all-round brains behind the Soviet space programme. Most importantly, he was trusted by the Kremlin to deliver success. But in January 1966 complications developed during apparently routine surgery for an intestinal polyp – although reports vary – and Korolev died. It was a setback that would have severe repercussions for the Soviet space programme. Korolev’s importance was such that his very existence was widely unknown outside top Soviet political circles. The Kremlin had feared he would become an assassination target for the CIA, and even Soviet cosmonauts had only known him by his first name.

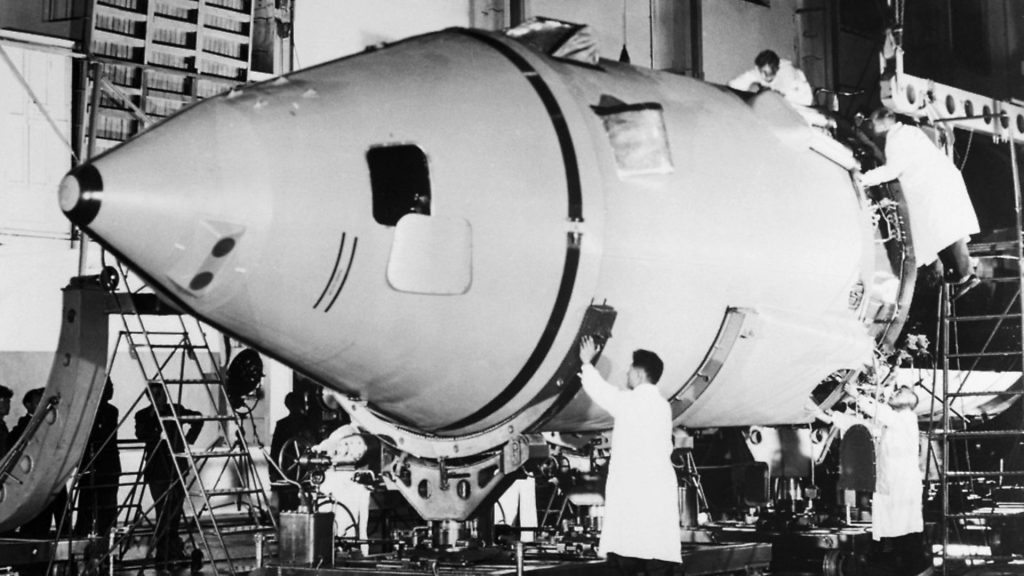

Under Korolev the USSR had already begun to evolve the rockets they hoped would take them to the Moon – the Proton-K, intended for a lunar flyby and the extremely powerful, 105-metre tall N1, intended for a lunar landing. Korolev’s plan was to have cosmonauts on the Moon by the end of 1968, but his death changed all that. The unfinished programme was taken over by his deputy Vasily Mishin, a competent enough engineer but, ultimately, not the man required to successfully develop the N1 either technologically or politically.

The USSR, it must be noted, had already landed a craft on the Moon. Both they and the United States had crash-landed probes onto the surface in the early 1960s but Luna 9 completed a soft landing in February 1966, sending back the first pictures of the Moon’s landscape. And although a payload of cosmonauts and their life support systems was always going to be a bigger and heavier challenge, the technology and precedence existed.

While the Soviet programme would have seen a similar configuration to Apollo with one spacecraft (the Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl) in orbit around the Moon and a lander (the Lunniy Korabl) being despatched to the surface, the Soviet lander would carry only one man, meaning the first cosmonaut would have walked alone on the Moon.

Although Hero of the Soviet Union, Gagarin, was a member of the squad of astronauts selected to train for moon flights, it seems that Alexei Leonov, the first man to walk in space in 1965, has the strongest claim to have been first choice to walk on the Moon. He never got the chance.

While the suspension of US launches caused by the Apollo 1 disaster had emboldened the USSR and their N1 programme was given priority, the Soviets encountered tragedy of their own. In preparations for flights to the Moon, in April 1967, their new Soyuz 1 capsule was rendezvoused to dock with unmanned Soyuz 2 and to undergo manoeuvres in orbit. Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov failed to complete the docking when his control system malfunctioned. But worse was to come. Soyuz 1’s parachutes failed on re-entry and his capsule hit the ground in a fireball. Komarov was the space race’s first in-flight fatality.

Any hope the Soviets had of taking advantage of the delays caused to the American programme suddenly waned. Work on the N1 was still incomplete. And when Apollo 8 circumnavigated the Moon in December 1968 it was obvious the Americans had regained the upper hand.

The Soviets needed to get back on track quickly. They had to prove their launch vehicle was as spaceworthy as NASA’s Saturn V, which had powered Apollo 8 to the Moon. They attempted the first trial of the N1 in an effort to leap ahead of the Americans. But on February 21, only a few seconds into the unmanned test launch, the engines tore from their mountings and fire ripped through the first stage of the rocket. Engine shutdown was automatic and 183 seconds into the flight N1 smashed into the steppe, 52 kilometres from its launch pad at Baikonur (then known as Leninsk, in what was the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic).

Three months later the Americans ran a dress rehearsal for a moon landing when Apollo 10 skimmed the lunar surface. It seemed the game was up. Only another disaster on NASA’s part could now save the Soviet Union from defeat in the space race. But instead it was they who would experience failure. In a final, possibly desperate, effort to prove the spaceworthiness of the N1 they attempted a launch on July 3. It was a catastrophe. Almost as soon as the rocket left the launchpad, debris began falling from its base. The N1 toppled and dropped back to the ground. The resultant detonation from 2,300 tons of fuel caused a blast regarded as the biggest non-nuclear explosion in human history.

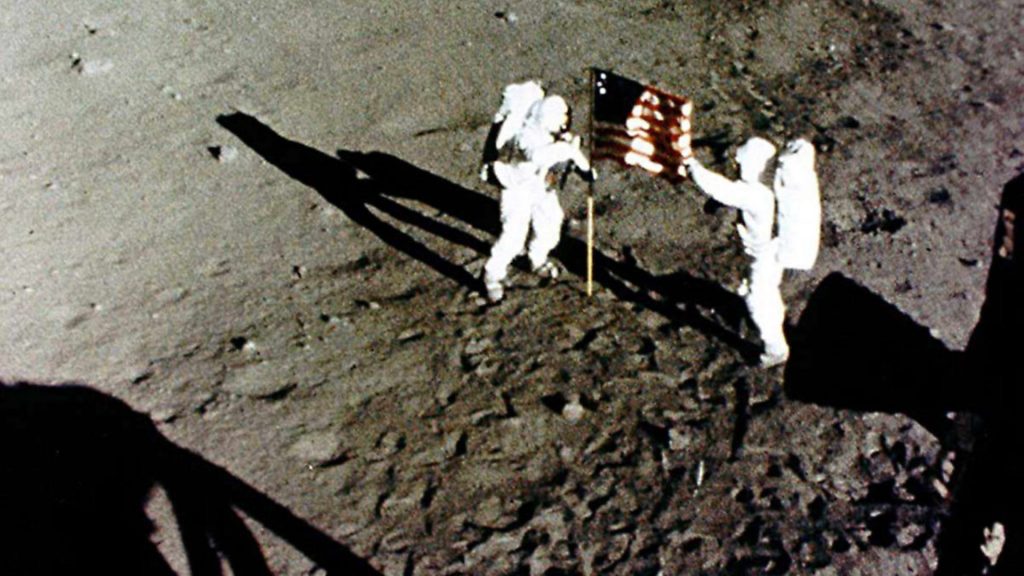

Because of the secrecy of the Soviet programme it is still unsure how many people, if any, were killed. But the devastation around the Baikonur space flight centre was total. Seventeen days later Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon. Mishin, already described by Gagarin and Leonov, as having poor knowledge of the spacecraft and the operation he should have been directing, and as ‘hesitant, uninspiring, poor at making decisions, over-reluctant to take risks and bad at managing the cosmonaut corps’, began to drink heavily and was ultimately replaced by Valentin Glushko.

Would Korolev have made a difference? It’s possible, but unlikely. Korolev’s strength was as a manager and as a broker between the politicians in Moscow and the technical team in Baikonur. And while he understood spaceflight and rocketry, he was not a great designer.

The N1 had worked well in early launches to put satellites into orbit but attempts to upgrade it to take cosmonauts to the Moon were piecemeal. Sergei Khrushchev, an engineer and the son of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier until 1964, knew Korolev. He described his approach as ‘let’s build it and see if it works’. So for all his brilliance in getting the Kremlin to see the political benefits of spaceflight, Korolev was less adept at the practicalities.

As a whole slew of space race anniversaries hove into view in the coming months, from Apollo 8’s lunar circumnavigation flight in December to the actual Moon landing in July next year, it’s illuminating to look back and consider how near the Soviet Union got to putting a human on the Moon and consider what the world might have looked like now if they had.

After all, the race was as much about ideology as it was technology. A victory in space for the USSR would have been equally significant back on Earth as the two superpowers continued to attempt to win hearts and minds and wage their proxy wars around the globe.