Last week’s elections may be the beginning of the end for the Labour leader. But even his departure may not save his party and Remain, says Steven Fielding

Labour’s performance in the European elections was appalling. For a party aspiring to form the next government, winning just 14% of the vote and coming third behind the Liberal Democrats would normally set the alarm bells clanging.

But these are not normal times. The elections were not even supposed to happen: Britain should already be out of the EU. And it’s not unusual for European elections to produce idiosyncratic results: turn out is invariably low – it was 37% this year – and with many uncertain about the function of the European Parliament, voters have often used them to give a kick to whoever is in government.

Yet, even though European elections produce a distorted picture of public opinion, they have influenced Westminster politics. UKIP topped the poll in 2014, encouraging then prime minister David Cameron to support an EU referendum. And this year they have already cost Theresa May her job as prime minister and cast a dark shadow over the contest to succeed her with leading candidates effectively repeating Brexit Party lines.

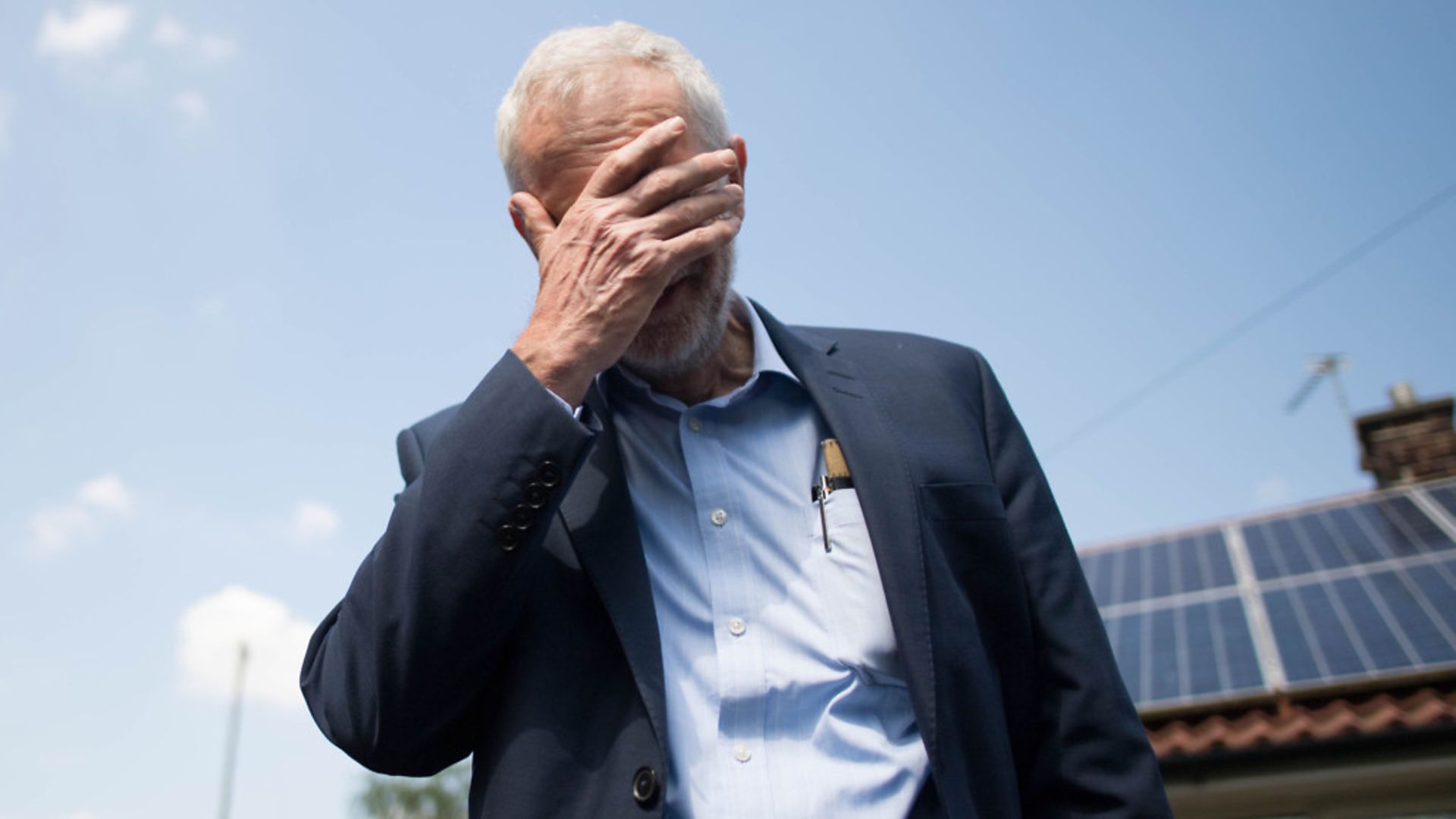

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership will also be shaken by the election’s aftershocks, although it will likely take time for them to work their way through the party.

Since the 2017 general election, Corbyn’s position has been secure because many members believed Labour’s unexpectedly strong showing was due to him and the radical policies he advanced. Even critics like deputy leader Tom Watson conceded that thanks to Corbyn, “something magical happened” in June 2017.

But there were other reasons why Labour did well. An ill-judged Conservative campaign headed by a leader with strikingly poor communication skills meant that instead of just being about securing a big majority for May’s Brexit plans, the election also became about the inequities of austerity. This allowed Corbyn to talk about the issues he wanted – like the very popular pledge to abolish tuition fees – and to discuss Brexit as little as possible.

Corbyn’s immediate response to the 2016 referendum was to accept the result but to transcend the Leave-Remain divide by being evasive as to what precise version of Brexit he supported. Initially this appeared a cunning ploy. For however well Labour did in 2017 Corbyn still failed to win a Commons majority. In order to do that the party needed to win largely manual working-class seats in which Leave voters predominate while holding on to more affluent constituencies where Remain voters are in the majority.

Corbyn hoped he could accomplish this difficult task by sidestepping Brexit in favour of talking up issues which united Britons, specifically the injustices of austerity, which he argued were more pressing than Britain’s membership of the EU. But as May’s inability to deliver a deal became ever more obvious voters began to identify ever more strongly as Leave or Remain.

This polarisation was also true of nearly 90% of Labour members and 75% of party supporters who backed another referendum in which most of them intended to vote Remain. For a man who said he wanted Labour to be a member-led party, Corbyn’s refusal to embrace these positions was paradoxical.

Corbyn’s implacability was not just due to electoral pragmatism. That was arguably a convenient cover for more basic – and ideological – thinking. The Labour leader has always been hostile to the EU. He voted for Britain to leave what was then the EEC in the 1975 referendum and, like many of his generation on the left, always saw the institution as a “capitalist club”.

If this meant Corbyn stood at odds with the majority of Labour members, many trusted in his intentions – especially as some prominent Remainers could be painted as Blairites exploiting the issue to undermine his leadership, one that appeared so close to power. But in the past few months pressure from prominent Corbyn supporters has intensified. The Love Socialism Hate Brexit group, which sees Brexit as “a Tory project and a massive assault on working class people”, has been particularly influential.

Labour’s performance in the European elections has seen loyalists like Emily Thornberry call for Corbyn to embrace a referendum and abandon a Brexit policy so vague few in the public understood it – and it appears to have lost both Leave and Remain supporters. But even if he is inclined to jump off the fence, the electoral damage might already have been done.

Some voters lost this time to the Liberal Democrats and other enthusiastic Remain parties might return to Labour in a general election: this kind of thing has happened after previous European contests. But with Leave/Remain identities now often trumping those of Labour/Conservative, Corbyn might have missed the bus.

This is not the end of Corbyn. But it might now be the beginning of the end. Many members still believe a Corbyn-led government is the greatest prize of all, even though the aura of 2017 has dimmed. If, in the wake of these results, he is challenged by a long-established critic such as Tom Watson, Corbyn will survive. But, before long, an ardent Remainer with more credibility among members – a Keir Starmer perhaps – may eventually mount a challenge.

By then, however, Britain might be out of the EU: thanks to a prime minister in Boris Johnson or Dominic Raab, Corbyn will probably get his Brexit.

This article is also available here.