They seem an increasingly unfashionable, unoriginal choice now, but package holidays were once little short of revolutionary. SOPHIA DEBOICK tells the tale of the first ever trip, and its visionary mastermind.

More than 160 years after Thomas Cook organised his first foreign excursion – a tour of Belgium, Germany and France – the business he founded is in the doldrums. The company has announced a £750 million bailout from Chinese firm Fosun to service its £1.6 billion debts.

The package holiday has long been in trouble. While the holiday market grew by almost two thirds between 1994 and 2004, the founding of the likes of Easyjet and Booking.com, along with internet usage jumping from 1% to 65% of the British population in that period, saw the DIY holiday take off and the share of the market claimed by packages fall by 10%.

It’s been a rocky road ever since, and as the concept wanes in the age of budget airlines and Airbnb, it’s difficult to grasp just how glamorous and exciting was the world that its pioneers first opened up to Brits in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the package holiday, as we would recognise them, first appeared.

Seventy years ago this summer, one of those pioneers went on a Mediterranean break expecting only relaxation. He ended up finding his life’s work, taking a few thousand pounds and creating a billion-pound industry, in the process revolutionising not just our holidays but our society.

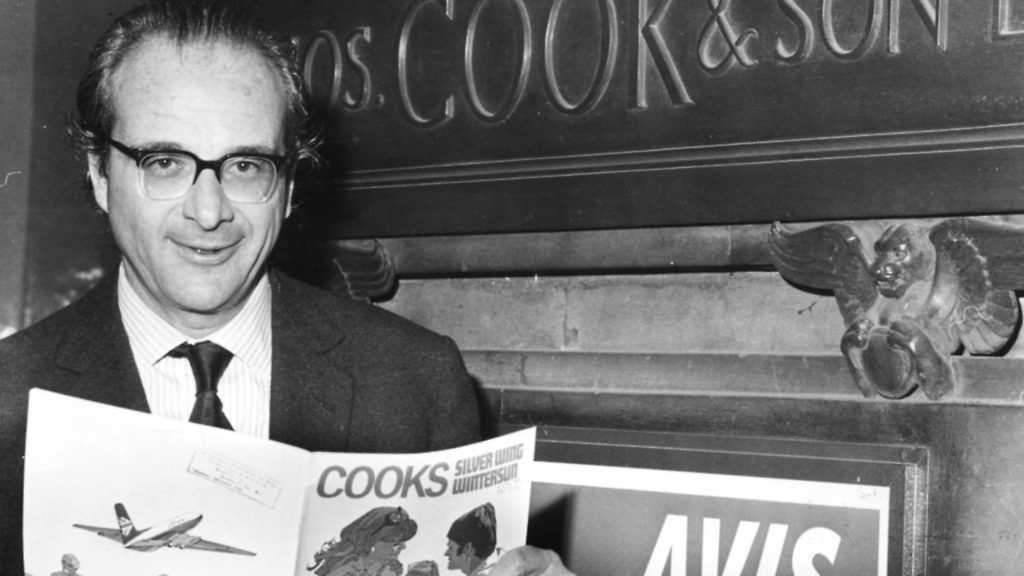

Vladimir Gavrilovich Raitz combined disparate qualities. A colourful, bombastic entrepreneur who wasn’t afraid to take risks, he was also charming, well-educated and honest.

His early life saw his family tossed on the waves of the twin forces of Soviet communism and Nazism. He was born in Moscow in 1922 to a middle-class Jewish family at a time of Leninist show trials, disease and starvation, as the social fabric was not so much torn as torched in the wake of bloody revolution and civil war. In 1927, as Stalinism took hold, he fled Russia with his mother. They never saw his father again.

Going first to Berlin to be with his maternal grandparents, he later moved to Warsaw when his mother married a Pole (his stepfather was later murdered by the Soviets in the 1940 Katyn massacre). When his grandparents fled Nazi Germany for London, he followed close behind, arriving in 1936.

Raitz had survived against the odds, and now fluent in five languages, he got a degree in History at the LSE and spent the war as a translator for Reuters. But once peace had broken out, his restless temperament drove him to take a leap of faith that changed both his life and British social history.

Raitz was 27 in the summer of 1949 when he first went to Corsica, invited there by a fellow Russian émigré. There he found White Russians making the Med their playground decades before the oligarchs arrived on their superyachts.

The northern fishing village of Calvi had become something of a Russian enclave – there was a water polo club (Les Ourses Blancs – the White Bears), and a town centre bar had been set up by a former member of a Cossack dancing team from Tajikistan, with financial backing from Rasputin’s assassin, Prince Felix Yusupov.

Raitz stayed at a tiny beachside resort, made up of army surplus tents, set up by the heir to a Tsarist-era bakery empire. Conditions were far from luxurious, but there was a dancefloor, a jazz band and copious amounts of food and, as Raitz told it in his 2001 memoir, Flight to the Sun, the wine, included in the price of a stay, “flowed freely”, while “romance flourished” among the Russians and the French, Belgian and handful of British paying guests.

To the ambitious Raitz this all looked very much like an opportunity. The presence of a rudimentary runway, built by the Americans during the war, inspired the idea to take this ‘package’ of bed and board and add easy travel to it by chartering planes, cutting the journey time from Britain from two days to a few hours. The modern ‘by air’ package holiday was taking shape in Raitz’s imagination.

He arrived back in London with a vision, but no capital to make it a reality. But then his grandmother died leaving him a not inconsiderable £3,000 and he ploughed it all into the Calvi scheme, setting up Horizon Holidays, renting an office on Fleet Street, and managing to get the rather cagey Ministry of Transport to issue a licence for charter flights.

A Horizon camp was set up, a brochure was made, and the following summer 300 people booked to fly out to Corsica for an all-inclusive fortnight, leaving behind a Britain of drizzle and rationing for sun, “meat-filled meals and as much local wine as they could put away”.

They paid £32 10s a head, a bargain given just the return flight to nearby Nice with the state-owned British European Airways cost £70.

The first flight left Gatwick on Saturday May 20, 1950, on a government-surplus Dakota DC3. It was only a third full and the holidaymakers found no airport facilities on landing. Things were similarly rudimentary when they got to the camp, where they were greeted by a spartan set-up of a toilet block, tents and a makeshift bar fashioned out of bamboo canes.

That bar was nevertheless the focal point at the camp. Run by one Jean Zemette, a Parisian who Raitz had headhunted from a Left Bank watering hole, the bar served a headbanging version of a Mojito christened a ‘Zem’, as Édith Piaf records blasted out.

The fun-starved Brits who made the journey loved it, but Horizon’s Corsican holidays offered more than just the chance to get well-oiled, and Calvi’s charming café-lined quay, unspoilt beaches, and the opportunity to swim in the crystal-blue Med made this an unforgettable experience.

Despite the success of Horizon’s formula with those who had taken the plunge, though, over the summer planes continued to fly out largely empty, meaning the Horizon coffers were in the same state by the end of the season.

But Raitz was not to be beaten. Investors were found and the firm began to grow, starting packages to Majorca in 1952. The following year chalets replaced the tents at the Calvi camp, and Horizon branched out in the unlikely form of pilgrimage packages to Lourdes, which were an instant success. Sardinia and the Costa Brava followed in 1954. But by then competitors were also on the rise.

The month before Horizon’s first flight, Gérard Blitz, who had once been the Belgian agent at the original camp at Calvi, founded Club Med and started running holidays to Majorca. Skytours had launched in 1953, and the granddaddies of the industry – Thomas Cook and the two companies that would go on to form Lunn Poly – were already offering a diverse array of trips, from sun to skiing.

When British European Airways began flying to Valencia in 1957 and invented the term the ‘Costa Blanca’ to market it, the age of the Spanish holiday was upon Britain.

Horizon had already added Ibiza, Menorca, Portugal, and southern Spain, centring on Torremolinos, to its roster by then and the foreign travel that was once the preserve of the well-off was fast being democratised.

With the number of Britons going abroad more than doubling between 1959 and 1967, Horizon rode this wave to reach the peak of its success in 1970, when it boasted its own hotels, scores of holiday destinations as far away as Tangier, and Raitz’s new invention, Club 18-30 (although its ‘sex sells’ approach was the invention of later owners ).

But the early 1970s holiday price war and the economic strain of 1974’s three-day week saw Horizon first taken over and then fold. Raitz lost his house, hit the vodka bottle and looked likely to sink too. But he got back in the game when asked to head up tours for Air Malta and was never out of the industry again. In 1999, then approaching his 80th birthday, he set up a new company to promote tours to Cuba, saying “working is too much fun even to consider the concept of retiring”.

Raitz was a citizen of the world who believed he was doing more than just giving people a couple of weeks of sun, sea and sangria, saying that the package holiday “brought with it what can only be described as a social revolution; the man in the street acquired a taste for wine, for foreign food, started to learn French, Spanish or Italian, made friends in the foreign lands he had visited – in fact became more ‘cosmopolitan’, with all that that entailed”.

He believed in the fundamental value of having a good time, but as a refugee, he knew that breaking down national barriers could make the difference between life and death. As Brexit and climate change threaten the future of the package holiday as well as so much else, Raitz and his fellow pioneers did much to encourage the open-mindedness and spirit of internationalism where hope to solve these issues surely lies.