Since the satellite TV revolution, much of football has changed. But much hasn’t. This stunning photo essay chronicles a pivotal era and captures the game’s eternal appeal.

John Williams discusses the beauty of Stuart Roy Clarke’s photographs.

I first met Stuart Clarke – the ‘Roy’ was added much later – in Leicester early in the 1990s. Football had been slowly emerging from the shadow of the terrible loss of life at the Bradford City fire and the shame of fatal English hooliganism at Heysel in 1985. But it was now in recovery mode again, this time from the extraordinary trauma of the spring of 1989.

I had been at Hillsborough on April 15, in the Liverpool seats. I was working at the time on a fans’ project for the Football Trust, so I had the role – not, I can tell you, a very pleasant one – of taking some officials around the ground immediately after the stadium was cleared to try to piece together exactly what had happened to cause such loss of life that afternoon. There was still debris on the terraces, scarves and scattered personal objects; the Leppings Lane fences were left gaping, horribly twisted.

The South Yorkshire police were soon showing us exit gates – the infamous Gate C – where drunken and ticketless Liverpool fans had supposedly broken into the stadium and contrived the killing of their fellow supporters.

Already, dazed young Liverpudlians, trying to make sense of what had happened, were contradicting the ‘official’ account, telling us that the gates had been opened by the police and that nobody had directed fans into the less crowded parts of the stadium. They showed us their unchecked tickets. Crazily, it seems now, it would take another 23 years for the innocence of fans and the full extent of the police mismanagement and cover up to finally be accepted by the authorities – and by much of the non-footballing public.

So, with the game slowly recovering from Hillsborough, England showing signs of imaginative life at Italia 90, and fashionable musicians starting to get into promoting the British game, this guy called Stuart Clarke contacted me and he came to meet in my cramped little university office in Leicester, strewn as it was at the time with folders, books and papers. It still is.

He knew that I had been doing some research with the Football Trust on fans, and that the Trust was now charged with helping to distribute funds for the national transformation of British football stadia demanded after the 1989 disaster. The English game at that time had been in a state of dynamic flux, with various bodies – the FA, the Football League and the PFA – all busily vying for advantage and control of the elite clubs and the national team for a new dawn.

The Taylor Report on events at Hillsborough had surprised the Thatcher government by actually demonstrating a wider interest in the game and the people who watched it, a complete mystery to Conservatives at the time. Lord Justice Taylor suggested that football deserved better and more coherent leadership.

He was right. It was rumoured that Taylor’s key recommendation – replacing standing terraces with seats – had been pressed on him by the main football bodies, who wanted a completely new direction for a sport long plagued by fan management issues. So now the money had to be found to fund a national stadium modernisation scheme likely to cost more than £500million in the first year. Coincidentally, satellite television, itself in financial trouble, was waiting to invest in top level English football, effectively to save its own skin. We all know now how that particular marriage of convenience worked out.

In fact, around this time I had been invited by Charles Hughes, senior football coach and guru theorist, to aid the FA, by contributing a chapter on fans and the role I saw for them in the sport, post-Hillsborough. It was meant for a mysterious, hush-hush FA document designed to map out a new future for the game in England.

I saw no other chapters and thought this was some minor internal report aimed for the FA Council to consider. But the Football Trust thought I should do it, so, I wrote my piece and moved on. To my surprise, it became a little-discussed section of the published FA Blueprint for Football, the 1991 plan for the historic dismemberment of the Football League and the launch of the FA Premier League itself. Funded, of course, by satellite TV.

In our first meeting, Clarke told me that he had been to art college, had got into photo-journalism in local papers in Watford, but was now doing his own thing, taking photographs of football supporters and stadiums.

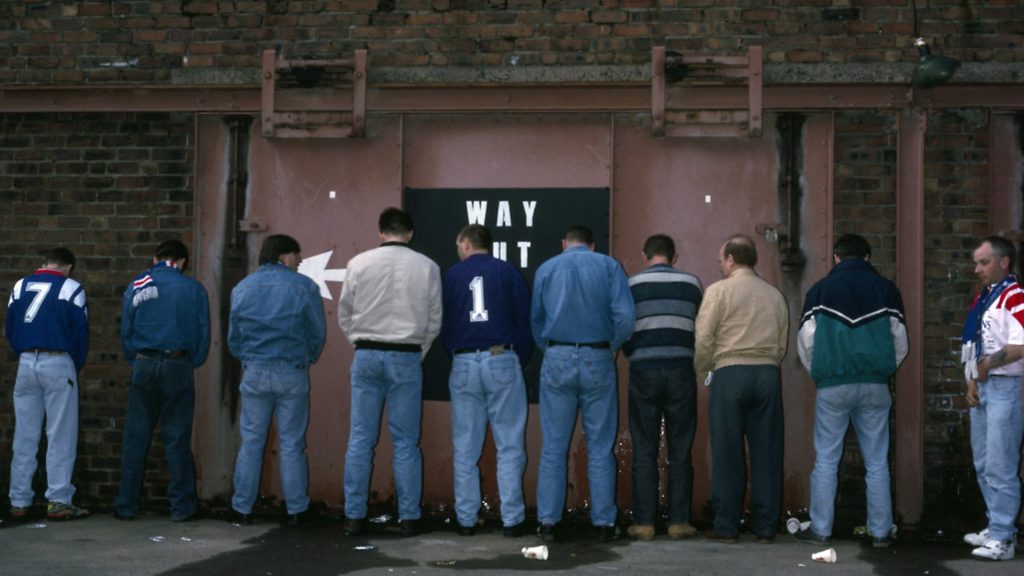

He was already on his Homes of Football journey. He also loved the way music and football were synergising. I liked him from the start. Those pictures he brought for me to see at that first encounter were like no photographs of the game, its people and its buildings, that I had ever seen. They were all in colour, large-scale, and nothing was staged.

They were invariably poignant and often funny, but never intrusive, always respectful of his subjects; ordinary men and women making something of the sport they loved. Or else, he was photographing stadium sheds, walls and stairwells, the spaces that others could only see as functional eyesores, some of them awaiting likely (and deserved) demolition. Clarke made them look like listed national monuments.

He certainly knew the game and its people – all that family time spent involved in local football in Hertfordshire and those Saturday afternoons down at a decaying Vicarage Road – but it was the artist’s eye he brought to a culture and its spaces that had been largely run down, abused and rubbished for decades that was so impressive in his work. His photographs captured the dignity and wild beauty of a sport and its people on the cusp of major changes.

In a way, his work in pictures complimented the early 1990s writings of the emerging new football literati, people such as Nick Hornby, who had brought an educated middle-class sensibility to interrogating the attractions of football for young men searching for ways of filling the supermarket masculinity trolley.

Like Hornby, Clarke was also a kind of class ‘outsider’, a man who had the knowledge, but also the kind of social distance needed to unpack and reveal the deeper meaning and aesthetic appeal of these weekly sporting rituals. He has done a wonderful job and has inspired many others since, to try to emulate his approach.

Neither of us knew, of course, quite where the English game was headed at that precise moment, exactly how substantial its social and material transformation might turn out to be. Clarke probably realised he was recording something important, something timeless, but also something strangely ephemeral. Naturally, I arranged a meeting for him with the Football Trust. Who was better placed to photograph for posterity how our historic football venues were now being gutted and modernised to meet the demands of a new era? Who better to show us how all this new money was being spent? He got the gig – I knew he would.

Clarke did some brilliant work for the Trust: grand portraits of once loved old terraces being mercilessly crushed by diggers; the steel struts of new stands sprouting up proudly into the sky; entire modern grounds evolving from nowhere. He naturally fused these studies into his wider project of capturing all possible manifestations of British fandom and the transformation of the sport in all its guises.

He also included here the working lives of people who were otherwise hidden behind the scenes of the professional game. Clarke has spent very little time on the glamour side of the moneyed Premier League; the top players and managers and their lifestyles is of little concern.

He much preferred tracing, before closure, the Accrington brick works which provided the materials for building northern Victorian football venues. Instead, he focused his lens on the tea-ladies and the boot-room volunteers; on the young women working on the coffee and food outlets inside and around grounds; and occasionally on the mainly honourable (if often misguided) British football club owners, before the oligarchs, the oil sheikhs and the international venture capitalists took over. He always wanted to examine the entrails, the guts of the sport more than its pampered and powdered surfaces.

His football work today spans capturing the early roots of the game – those cranky and violent forms of folk football which are still played by local men on the land and on feast days up and down the British Isles – and the enduring tale of local Sunday morning football, played on dog-shitted, uncut parks pitches with few decent facilities.

He wants to try to connect, at least in our heads, the lowest levels of play with the elite few who earn millions and have global profiles. It’s a tough ask, but he has certainly encapsulated the local game in all its camaraderie, importance and absurdity, as beer-bellied local men and determined young women try to defy space, time and the elements to bring home the points.

Recently, he has been carefully profiling the growing women’s game in England, unsurprisingly seduced by the energy, skill and lack of ego of top female players. These are rising sports stars who still ply their world-class talents mainly off our television screens, on muddied fields in front of audiences often numbered in hundreds rather than the tens of thousands that even mediocre male players manage to drag in.

England’s women may yet win the World Cup in France in 2019. I wouldn’t bet against it. I would bet that Clarke will be there if they do.

A selection of Clarke’s work is currently being exhibited at the National Football Museum in Manchester. You really need to see it. His new book The Game, includes extended conversations I recently had with him in my Leicester home about the role of photography in mapping the history of the game, and how his own work has covered the last 30 years of convulsive change in British football. He is a good mixer and collaborator, and a great talker.

And, remarkably, Clarke’s almost child-like enthusiasm for the game and its people never seems to wane. He still travels most weekends, all over Britain to football at all levels, convinced he has not yet seen it all. He remains completely confident that he will find something different, something new that he can play back to us football junkies, about how we imbibe and play and live our lives through the world’s greatest game. He always manages to persuade me that he can find that image, that shot, which can tell the whole story better than a mere scribe can. I’m a believer, you see. To my mind, if anyone can, Stuart Roy Clarke can.

• John Williams is an associate professor in sociology at the University of Leicester

• The Game: 30 Years Through the Lens of Stuart Roy Clarke continues at the National Football Museum in Manchester, until March 17; The Game is published by Bluecoat Press