As Estonia celebrates its 100th anniversary, SI HAWKINS finds an unusual national symbol at the centre of commemorations, which chronicles every twist of the country’s exceptionally eventful century

For a nation which has endured so many sea changes over the last 100 years, the Estonian submarine Lembit could hardly be a more fitting symbol of national pride.

Built by one country for another, coveted by a third and seized by a fourth, she escaped one of history’s worst maritime disasters, plus several fires and a wrecking order. As the Iron Curtain fell, the indomitable craft – dubbed the ‘immortal submarine’ – even survived a dramatic armed stand-off to emerge as an emblem of her country’s regained independence.

Now, as Estonia celebrates its centenary, Lembit is once again in the nation’s focus, as a centrepiece of the commemorations.

Lembit’s own story opens at the very birth of the nation in the Estonian War of Independence, which broke out in November 1918 as the Bolsheviks engaged in a wider conflict to establish control over the former Russian empire.

Britain – specifically its navy – played an important role in the war, providing arms to the Estonians and protecting their coast from the Soviets; ultimately the new nation prevailed and its independence was internationally recognised in 1920. Estonia’s naval leaders were swift to suggest that it should buy some submarines – a powerful, defensive weapon for a small, coastal country – and the UK was first choice to help.

‘There was a consensus that we must order these ships from Great Britain, because Britain aided us in the War of Independence,’ says Arto Oll, an Estonian historian who has written a book about Lembit.

‘The Estonian navy always tried to base its structure and education on the Royal Navy; it is even mentioned in British foreign office documents in the 1930s: ‘of all the nations in Europe, Estonia is the one who is weirdly still very thankful to us that we came to her aid.”

The Estonian/British dynamic was certainly intense during the shipbuilding process.

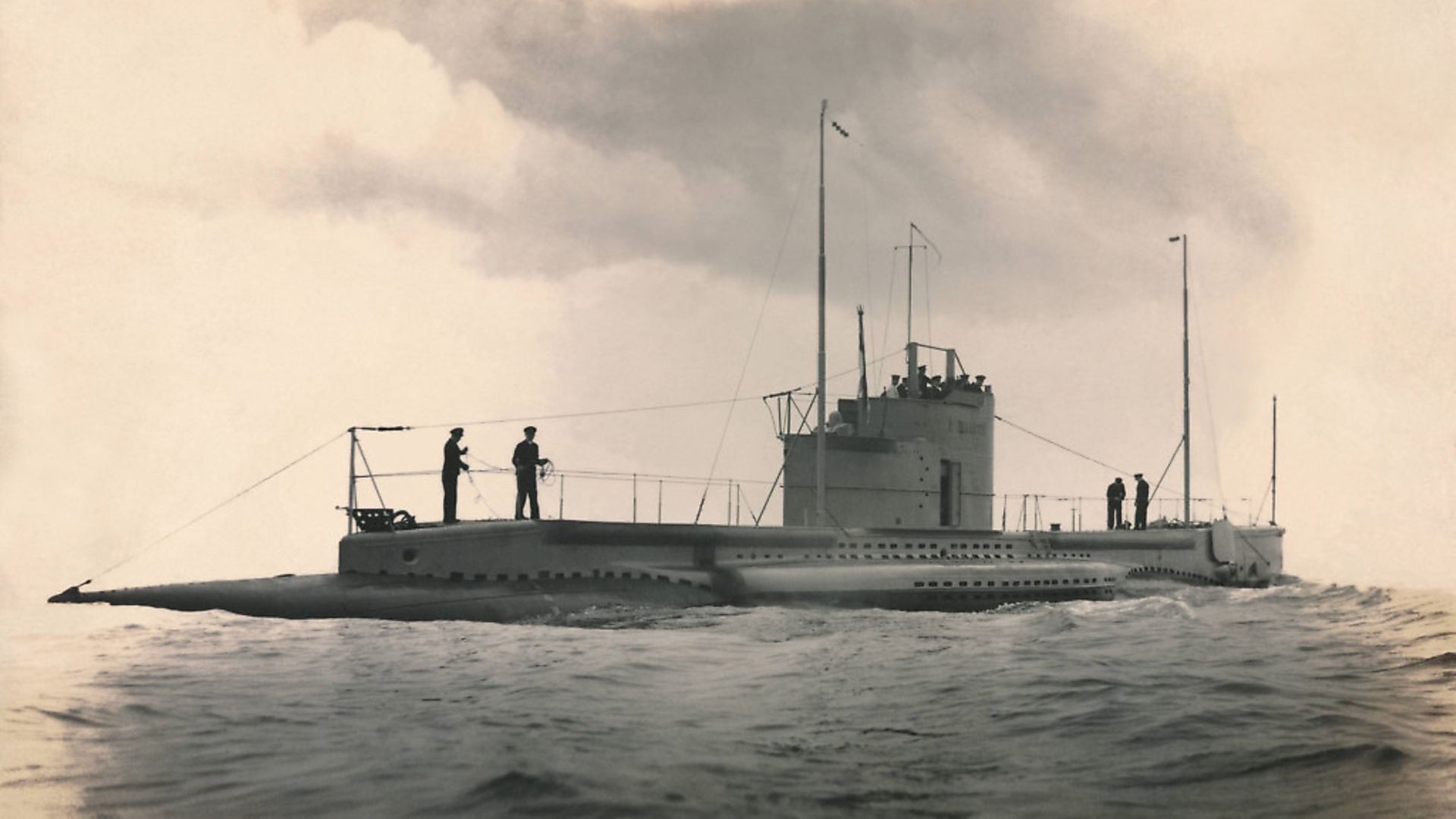

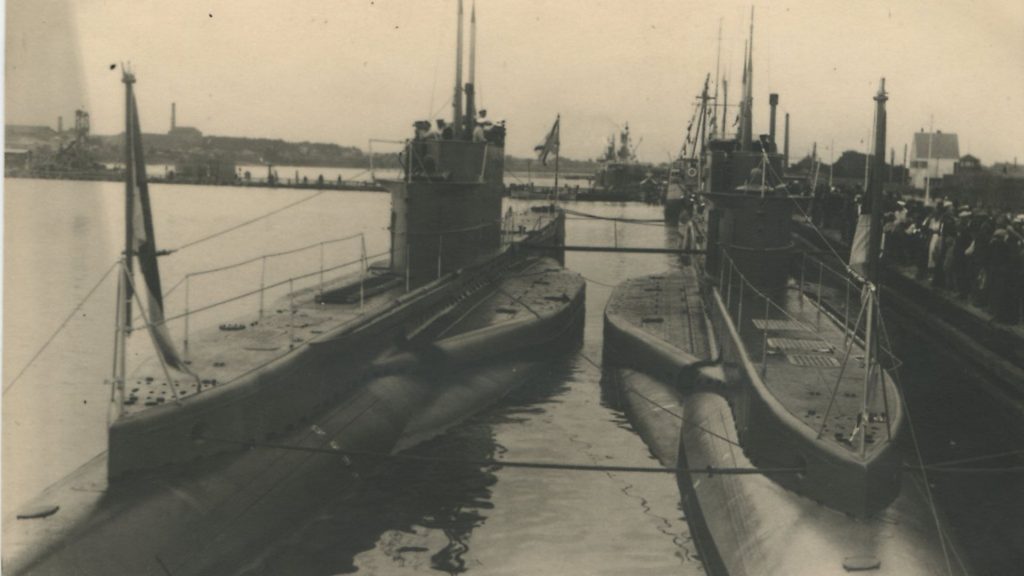

The job was ultimately given to Vickers-Armstrongs – now part of BAE Systems – but it took almost two decades for the purchasers to decide exactly what their new submarines (they ordered two) required. Eventually, in 1935, building began on a whole new category of vessel: the 60ft Kalev class, named after Lembit’s identical sister ship.

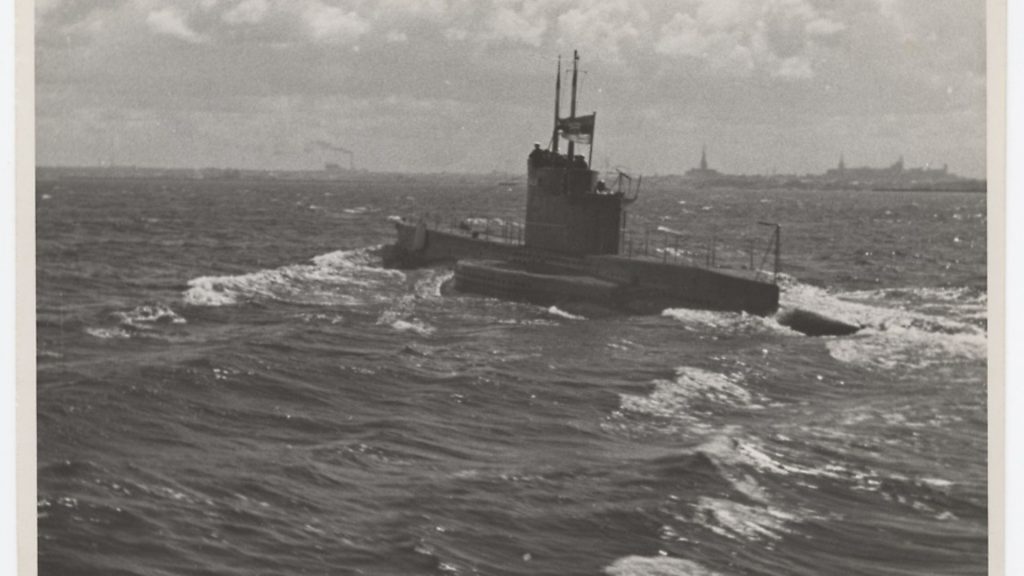

Much judicious doomsday thinking went into those plans, and one major requirement was compatibility. The ships would need to be adjustable for different types of torpedo, British and Finnish: Estonia had been secretly co-operating with Finland to counter potential incursions by their ominous neighbours, the Soviet Union. If Tallinn fell and their British torpedoes ran out, Lembit and Kalev had to be able to adapt to accept bigger torpedoes in Finnish ports.

The two subs also required a reinforced ice-breaking hull – they were built for patrolling and minelaying in the Baltic Sea – and would be extra-wide to house dozens of mines. Their Swedish/German-made bombs intrigued British intelligence, said Oll. ‘The British report says ‘they’re using some weird mines that resemble a German mine but we don’t know what they are’.’ When the mines were transferred to Britain for loading, one of them went mysteriously missing – Oll suggests it was taken by the British for further investigation.

During the building process, Estonia frequently sent inspectors over, who were ‘strict, kind of nosy, but very professional,’ according to Vickers’ records. Then the future crew arrived too, for training.

The submarines officially became Estonian after their launch from Vickers-Armstongs’ Barrow-in-Furness yard, in 1937, ‘The flag was hoisted, people saluted,’ said Oll. ‘And only then were they given the detonators for the torpedoes.’

Estonia’s ownership of the submarines quickly became complicated, however. Although Estonia had been briefly occupied by Germany towards the end of the First World War, relations between the two had since strengthened, as a result of a shared suspicion of the USSR. As the Second World War loomed, therefore, Berlin sent a request to Tallinn to take possession of the submarines – to keep them out of Russian hands. It was seriously considered by the Estonians, but they ultimately deemed it a betrayal of the Royal Navy, since the Germans would inevitably pore over the vessels to learn more about British technology.

Five weeks before the Second World War began, however, Germany and the Soviets signed their non-aggression pact and Estonia was left to fend for herself. However, the country boasted a proud civilian army (the border city Narva still does, in fact), while Tallinn Bay was thought to be virtually impregnable due to its coastal defences, submarines, and mines.

So what happened next still bewilders historians. Led by contentious president Konstantin Pats, Estonia simply waved Soviet forces in and handed them their military resources, including Lembit and Kalev: the infamous ‘silent surrender’. So brutal was the Soviet occupation that when the tide turned and the Nazis captured Estonia in 1941, they were seen as liberators by many. ‘When the Soviets came in they executed – massacred – children, women,’ said Oll. ‘It was very hardcore stuff that happened here.’

The Soviets’ attempted evacuation of Estonia in 1941 via Tallinn Bay – then awash with German and Finnish mines – was hardcore too. Lembit and Kalev, now sailing under the flag of the Soviet navy, slipped through but the surface fleet of troop ships was not so lucky. The operation, sometimes described as Russia’s Dunkirk, resulted in one of history’s bloodiest naval disasters with a death toll conservatively put at more than 12,000.

The submarines soon became casualties too, although with wildly differing consequences. In the autumn of 1941, the Kalev vanished while on patrol in the Baltic, leaving few clues as to her final resting place. Her most likely fate is that she struck a mine, and was completely destroyed.

Almost a year later, Lembit almost suffered a similar fate. During an attack on an enemy convoy, she was targeted with depth charges from the defending ships above. The vessel dived in an attempt to escape but the new Soviet crew – not as well drilled as the previous Estonian one, according to Oll – had left the lighting system on, causing a fire to break out. Lembit survived though, and limped into port.

The stricken vessel required a year of extensive repairs, during which the war in the Baltic raged on, with the Soviets enduring particularly heavy losses. The period of convalescence may have saved Lembit from a Kalev-like fate, and she survived the conflict.

Lembit was ultimately credited with sinking several Axis vessels but, according to Oll, her eventual war record should be taken with a pinch of Siberian salt. ‘We know the Soviet submarine force didn’t achieve much,’ he said. ‘They created their own history.’

The semi-retired sub was kept busy in the post-war decades, diving in a Russian river to acclimatise potential submariners, but by the late 1970s she was due to be scrapped. Someone, however, spotted the potential for propaganda and Lembit returned to Tallinn as a floating exhibit, a symbol of unified Soviet/Estonian strength.

And that seemed to be that, until the Berlin Wall fell and the Baltic nations re-declared independence. Lembit suddenly found a new purpose, and saw more action. The Soviets – retreating from Tallinn once more – resolved to take Lembit with them again. But a brief stand-off between the Russian guards and some armed Estonian servicemen saw her remain – another silent surrender.

The veteran vessel – newly-classified 001 in Estonia’s nascent navy – returned to active service, stationed in Tallinn harbour, monitoring the waters for suspicious maritime activity. Her latest incarnation – surely her last – is in Tallinn’s Seaplane Harbour Museum. It took several days to slide Lembit in to the converted hangar, in 2011, via inflatable pontoons. The museum is decorated with blown-up recreations of her original blueprints, which were discovered in archives in Cumbria around a decade ago.

The museum is one of Tallinn’s main attractions and has been deeply involved in centenary celebrations, which are running throughout 2018 and lasting until 2020. Indeed, earlier this month the Earl and Countess of Wessex visited the submarine and the museum to open a new exhibition commemorating Britain’s role in Estonia’s War of Independence, which ultimately led to the purchase of Lembit.

For the submarine, and for Estonia, the 100 years since then have been anything but plain sailing.