A new exhibition, Magic Realism, Art in Weimar Germany explores the stunningly creative period that took place in Germany between the wars.

For the poet Stephen Spender, 1929 was the last year of that ‘strange Indian Summer – the Weimar Republic’.

He had revelled in the decadence of Berlin, living it up with the likes of writer Christopher Isherwood and the poet W.H. Auden and to them Germany was a paradise where there was no censorship and ‘young Germans enjoyed extraordinary freedom in their lives’.

A new exhibition at Tate Modern – Magic Realism, Art in Weimar Germany 1919-1933 – celebrates that freedom in what, far from a paradise, was a time of tortured creativity, a world disfigured by pain, perversion, rage and disgust.

Look no further than George Grosz and his disquieting work Suicide (1916). A man has shot himself and is sprawled on the ground, grinning obscenely in his death throes. Dogs roam past, shadowy figures scuttle into the dark, another corpse hangs from a lamp post. But the world goes on its corrupt and heartless way; a harridan of a prostitute, red lips and rouged nipples, looks on, indifferent to the death and her own degradation as she waits for custom.

Suicide is one of 70 works on display, most owned by Greek shipping magnate George Economou, which were born out of the turmoil of Germany’s Weimar Republic,. This lasted from the end of the First World War to Hitler’s rise to power as chancellor in 1933.

It was a time of upheaval. The Bolsheviks had seized control in Russia, the Austro-Hungary Empire had been dismembered. Germany was hamstrung by punitive reparations imposed by the allies, industry was hit by strikes, unemployment was high and inflation higher. In 1922, a loaf of bread cost 163 marks, one year later it cost 200 billion.

Out of this chaos emerged thinkers, artists and provocateurs including German historian, photographer and art critic Franz Roh, who, in 1925, coined the phrase Magic Realism, long before the magical realism of the South American writers.

He wrote: ‘To depict realistically is not to portray or to copy but rather to build rigorously to construct objects that exist in the world in their particular primordial shape.

‘For the new art it is a question of representing in an intuitive way the fact, the interior figure of the exterior world.’

As definitions go it is pretty impenetrable. A little clearer were the aims of the New Naturalism (Neue Sachlichkeit) which sprung up around the same time and divided into the artists who took actual things from the world of real events and classicists who ‘search for timelessly valid object to realise in art the eternal valid laws of existence’.

Roh was influenced by Freud who had just published The Uncanny (‘Das Unheimliche’) in which he examined the experience of perceiving a familiar object or a person in a strange situation with unsettling results.

Unsettling it is. Disturbing and destructive too. As Grosz wrote: ‘In this faithless and material time one should use paper and slate to show people the devilish mug concealed in their own faces. Let us tear down the storehouse of ready mades and all the manufactured junk and show the ghostly nothing behind them.’

A similar nihilism gripped his contemporary Otto Dix (1891-1969) who like Grosz (1893-1959) served in the trenches. Grosz suffered a breakdown and was admitted to a military mental asylum where doctors declared him unfit for service on grounds of insanity, while Dix fought on the Western Front and won the Iron Cross.

Utterly disillusioned, Dix captured his experiences in a series of etchings entitled Der Krieg (‘The War’), a savage denunciation of the conflict with unrelenting depictions of the dead, the dying and the shell-shocked, the shattered landscapes and the graves.

Surprisingly perhaps they were drawn after a 1922 series on the circus which greet the visitor to the exhibition. These are not the happy-go-lucky images one might expect. His circus is peopled by the grim and the bizarre.

The couple in Scorners of Death with their jaws clamped in tension are like living skulls, Lili, Queen of the Air is demonic, in The Illusion Act a woman’s head on a spider’s body dances between a skeleton and a circus master. Another entitled Sketch has a grotesquely- grinning dwarf apparently shooting at a globe while a lanky performer is impaled by an axe and giant screw.

Everyone is ugly. Who, or what, is about to feel the lash of the whip brandished by the Tamer with her hard face, and stunted body? This is a world of the degenerate and the misfit, where the exotic and the permissive is the norm.

It is a society too which had a gruesome, often misogynistic, fascination for killings, with the newspapers dwelling enthusiastically on the latest atrocity. In Dix’s Lust Murder the killer laughs manically as his victim, a woman, lies spreadeagled by her bed, naked and bloody.

It is hard not to think that work like that owes as much to the predilections of the artist as the pressures of the time.

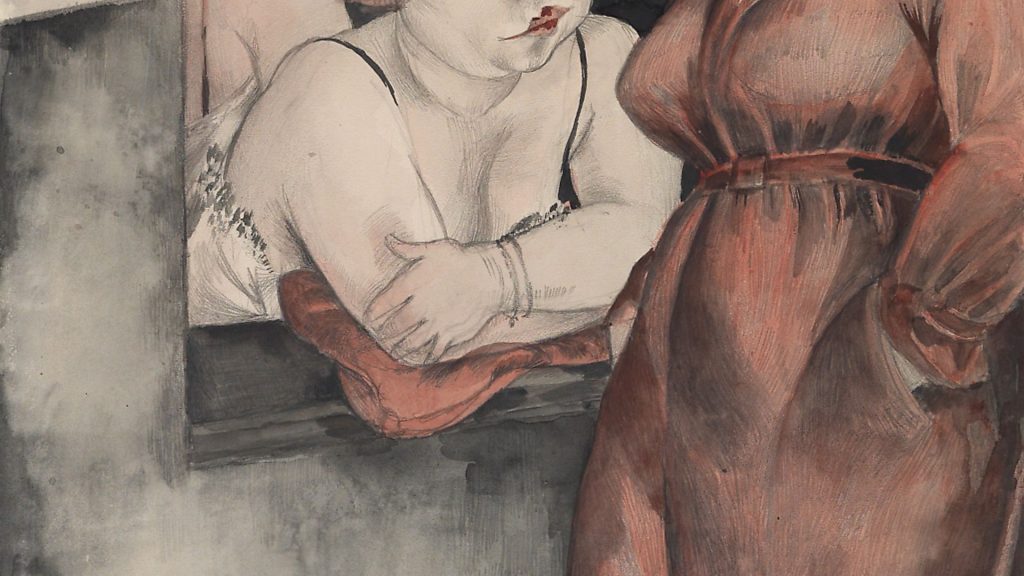

There is a definite undertone of fetishism in Rudolf Schlichter’s The Artist with Two Hanged Women. The fact that he puts an artist – maybe even Schlicter himself – in the frame suggests an unhealthy fascination for degrading women, and indeed for some years the artist earned his living from drawing and selling pornography.

The Tate thought long and hard about even including the painting in the exhibition but decided to acknowledge that it reflected the artist’s attitude towards women, however shocking.

Intriguingly, in the next room Lady with Red Scarf is a striking portrait of the artist’s wife Evie, hands across her body staring boldly out of the picture. It looks a straight-forward enough image but one has to take a second look when it is revealed that she apparently indulged his various fetishes. Is her gaze bold or is it fearful? Complicit?

What to make of Conversation about a Paragraph by Richard Müller? He specialised in exotic nudes, often attended by alien creatures, and here two naked women, one seated wearing only a hat, the other sprawled on a bed with what could be the tattoo of an apple peeping from her nether regions. An angel, painted many years later in the 1960s, flutters by.

Perhaps this meets the Magic Realism label as well as any. It is certainly mystifying but it is also grounded in a political issue of the day. The small symbol for a paragraph hovers in the air between the women. It refers to paragraph 218 in the German constitution which at the time was debating women’s rights to abortion.

Social issues and politics are all entwined with the hedonistic life immortalised by Christopher Isherwood in his 1939 novel Goodbye to Berlin which inspired the film Cabaret in 1972. It captured a breathless dash for pleasure, drink, cocaine, crime and casual sex enjoyed perhaps by the Girl with Pink Hat (1925) by Hans Grundig with her smudged make-up, heavy mascara and red lips. Judging by her basilisk gaze she doesn’t seem to have enjoyed herself very much – or maybe she enjoyed herself too much.

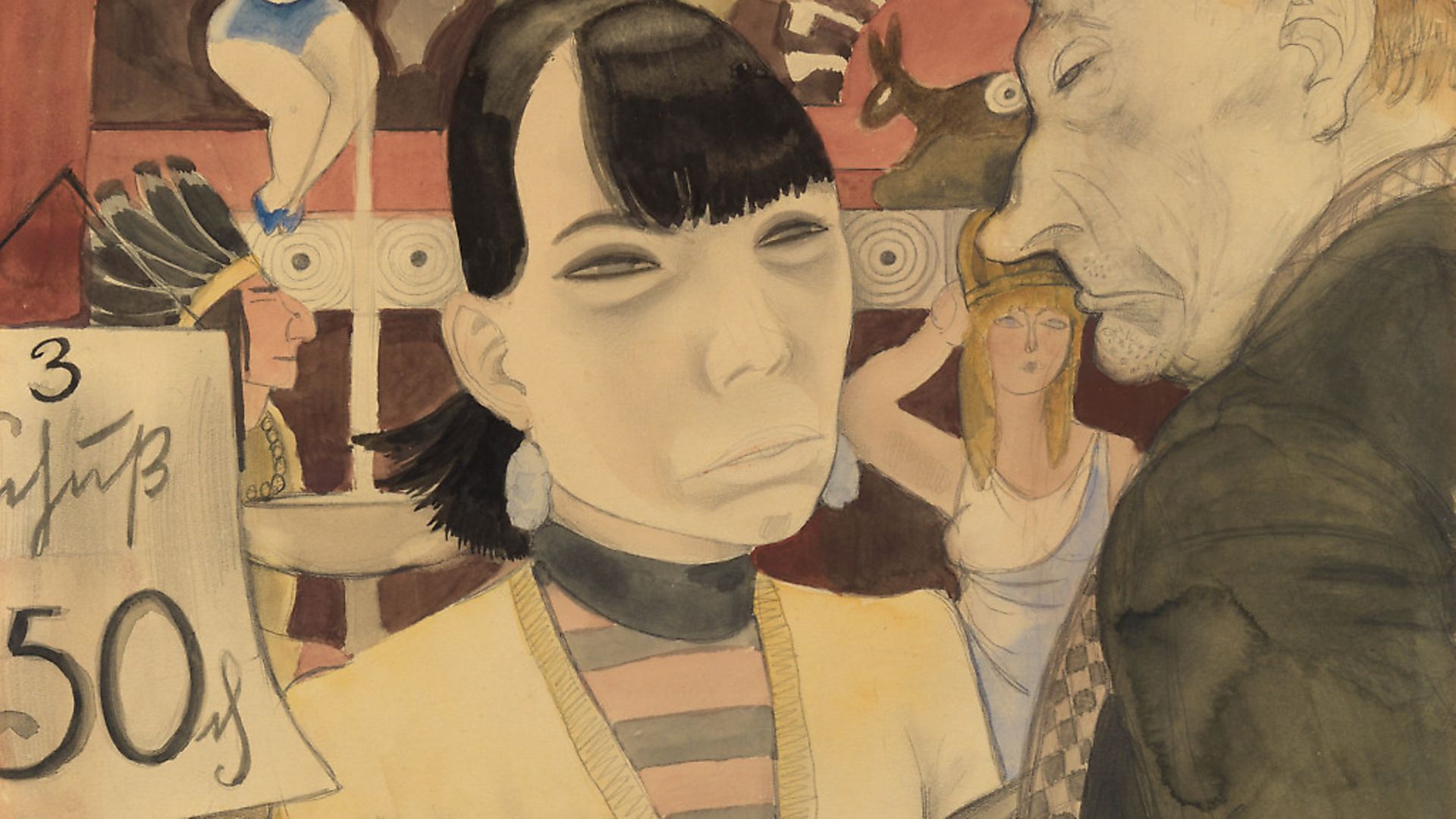

Her bleakness is shared by the characters in the works of Jeanne Mammen, who worked for satirical and fashion magazines. Maybe that’s what helped her portray the emptiness behind the glitter of the cabaret in At the Shooting Gallery and Boring Dolls, young women who treat the world with a sardonic mix of nonchalance and boredom. Three prostitutes in Brüderstrasse (‘Free Room’) stand by a doorway with the sign Zimmer Frei, registering nothing but indifference and contempt for their potential clients.

‘Come to the cabaret, old chum,’ sang Sally Bowles in the film – but she might have added: ‘Don’t expect to enjoy yourselves.’

From that jaded party it is quite a leap to the intense religious works of Albert Birkle. Religion was not seen as being an important part of Roh’s vision but one of Germany’s most sacred paintings Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (c 1512-16) had been moved in 1917 from war-torn Alsace for safety and had become an object of pilgrimage.

It inspired Birkle, only 21, who also saw active service, to produce a series of tortured images such as Crucifixion and The Hermit, both cries of anguish for the lost souls of the war and, perhaps, a means to find a salve for the confusion of the times.

This hurly-burly of creative discord came to an abrupt end with Hitler’s rise to power. Degenerate art was banned and several of the artists fled. Grosz, for example, was charged with making pornographic images and dubbed ‘cultural bolshevist number one’ but even Hitler’s ruthless purge could not destroy all the works.

In his wonderfully original show about the music of the period, Weimar, which was on at London’s Barbican Centre over the summer, Barry Humphries recalled visiting an exhibition of German degenerate art with David Hockney.

‘Why had so many pictures survived the Holocaust?’ he wondered.

‘Because somebody loved them,’ replied Hockney.

Actually, they are hard to love but it is impossible not to admire their dark audacity.

Magic Realism, Art in Weimar Germany 1919-1933 is on at Tate Modern until July 14, 2019