CLAUDIA PRITCHARD on an artwork, an exhibition and a book which all demonstrate the way that artists have been inspired by trees.

In our new, more outdoor life, trees have been a consolation, ever-changing but constant, by turn prickling with promise, brimming with plenty, stripping down for winter, and bubbling into life again. As the plague year goes full circle, these sturdy companions are being celebrated with more passion than ever.

At Somerset House in London a real grove is to take root, albeit temporarily, in the central courtyard, in an installation by artistic director of the London Design Biennale, Es Devlin. Her Forest for Change overturns the original concept of the quadrangle, masterpiece of the Enlightenment.

Discovering that trees were originally forbidden there, she resolved to “counter this attitude of human dominance over nature, by allowing a forest to overtake the entire courtyard”.

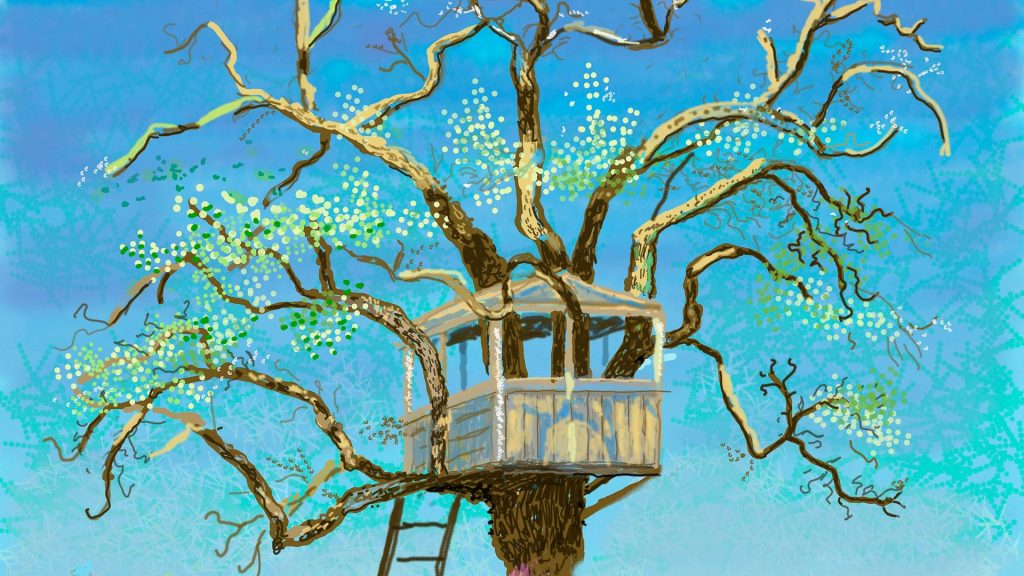

Meanwhile across the West End at the Royal Academy, the latest exhibition dedicated to the irrepressible David Hockney comes out of its own hibernation, the lanes and vistas of his adopted home of Normandy vibrating with colour in new work.

Hockney began experimenting with making art on his iPhone in 2007, moving on to his iPad and Stylus three years later.

The 116 pieces in this latest outpouring from France are ‘painted’ on the iPad with vigorous ‘brush’ strokes, before being printed on to paper, much scaled up, so that every detail of Hockney’s depiction of the natural world is on view.

Created in the spring of 2020, the season’s story unfolds with trees as heroic characters, impervious to the elements, dwarfing and sheltering all around them.

Such a love affair with landscape was not always considered suitable for a Royal Academician.

A hierarchy of subject matter once looked down on the natural world, as influential academies drew up orders of respectability.

In the vanguard was the French Academy, where in 1669 secretary André Félibien ranked the genres from the noblest, history painting via portraiture and genre painting down to landscape and still life. Once artists broke free of those limitations, the tree grew and grew in artistic stature.

They also grew in years. Those being harvested in Van Gogh’s Women Picking Olives (1889) could be many centuries old. He painted three versions, experimenting with his palette.

The first, in a private collection, he described as “more coloured with more solemn tones”. The second was more subdued. The third, which was intended for his sisters and mother Anna comes with the artist’s appeal: “I hope that the painting of the women in the olive trees will be a little to your taste,” he wrote to his family. “I sent [a] drawing of it to Gauguin… and he thought it good…”

Women Picking Olives is one of the works featured in another celebratory work, The Book of the Tree: Trees in Art. In it, artists reveal their workings. “Cypresses are well worth the effort of looking at them from close at hand,” wrote Van Gogh to his brother Theo. “It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape, but its one of the most interesting dark notes, the most difficult to hit off exactly that I can imagine.”

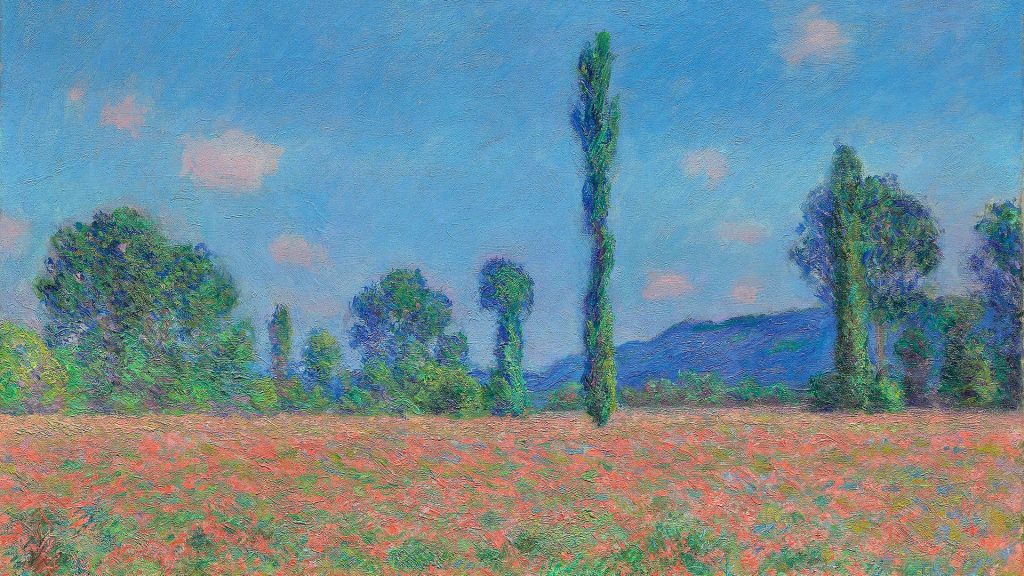

As well as the great series of Rouen Cathedral, haystacks and gardens at his home Giverny, Claude Monet created his Poplars series over eight months in 1891.

The trees were in a marsh along the banks of the river Epte, upstream from the artist’s home and studio. Taking a small boat to join the river where the poplars curved in single file, Monet achieved three groups of paintings.

In one, the trees march out of the top edge of the canvas, in another group there are the same seven trees, their watery reflections pushing down, and in another group only three or four poplars.

The artist was obliged to buy the very trees themselves, when they were put up for sale by the local authority before he had finished his project.

When the work was done, he sold the trees, grown for cabinet-making, to a lumber merchant. And it was on the proceeds of the haystacks and poplars series that he was able to buy the old cider-press at Giverny that became his home and inspiration for the second half of his life.

Artists not necessarily associated in the first instance with landscape painting also have their love affairs with trees.

Piet Mondrian, best known for his monochrome grids with blocks of primary colours, was intensely interested in the way that trees punctuate and divide the vista. In their vertical slices through the horizon we witness the beginnings of distillation into the grid.

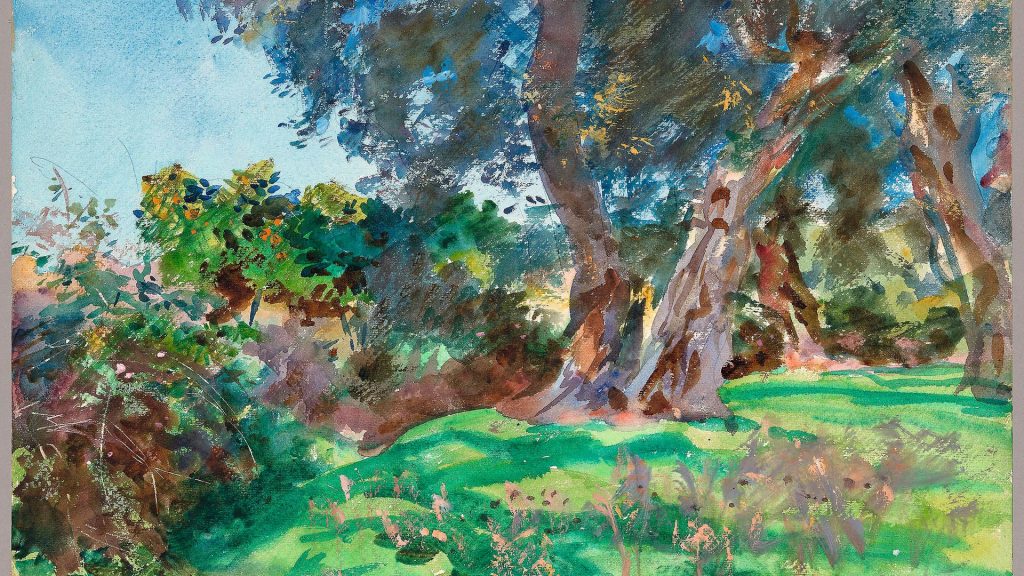

In an entirely different artistic field, the society portraitist John Singer Sargent turned his back on the fashionable world in 1909 and headed for Corfu, painting and sketching olive trees that would underpin a submission to the Royal Academy, Albanian Olive Gatherers (1909, now in Manchester Art Gallery) and, in the same year, Olive Trees, Corfu, with its fast, loose brushstrokes, legacy of the impressionism in France that had liberated artists bold enough to follow suit.

Perhaps more likely to exercise his distinctive, deliberately naif style on the natural world was Henri Rousseau – the customs officer dubbed le Douanier Rousseau – who for all the apparent simplicity of his work was a knowing client of the go-to dealer, Ambroise Vollard, to whom he consigned The Banks of the Bièvre near Bicêtre.

Painted around the same time as Sargent’s productive Corfu expedition, it shows the apparently blissful environs of a working class community to the south of Paris near a tributary to the Seine.

Figures in peasant dress march along a tree-lined path and in the background is the 17th-century Aqueduc d’Arcueil. Today the Bièvre is culverted, but in Rousseau’s time it was a foul and polluted.

While Somerset House’s Forest for Change illustrates our responsibility to an environment corrupted by industrialisation, Book of the Tree co-authors Angus Hyland and Kendra Wilson are uncompromising in their respect for trees, conservation’s warriors. “If only people would be more like them,” they write, “quietly filling the world with oxygen instead of hot air.”

Es Devlin’s Forest for Change is at Somerset House from June 1 to June 27; David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020 is at the Royal Academy from May 23 to August 1, and from August 8 to September 26; The Book of the Tree: Trees in Art by Angus Hyland and Kendra Wilson is published by Laurence King at £14.99

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk