It was supposed to be the year to catch up on your reading. Don’t worry if you didn’t get through too many books. CHARLIE CONNELLY has some more to recommend…

Sooo, have you read much this year? Like many people I had great ambitions of tucking in to some seriously weighty volumes once the lockdowns and restrictions began and lined up some proper whoppers to get my teeth into.

Two in particular had been sitting unread on my shelf for, well, years and I was determined to see off both of them: Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry, an epic western in which a bunch of retired Texas Rangers drive cattle from Texas to Montana over the course of 840 pages, and the collected letters of John Steinbeck, a book that weighs in at an shade under 1,000 epistolary pages (how did he have time to write any books?). I was also anticipating The Mirror and the Light, the final instalment of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, which rivals the Steinbeck in page count and was a hardback to boot. Pass me the biscuits, I declared as I plumped up the sofa cushions, I’ll see you on the other side.

Of course, the Steinbeck and Mantel remain unopened while I’ve just checked the McMurtry and my bookmark is sitting between pages 23 and 24, where I left it back in the spring. I’m not going to beat myself up about this – although I could do a pretty thorough job using the books themselves – because I am far from being the only one to struggle to concentrate on anything for long this year.

It’s all to do with the anxiety that’s been thrumming away at the core of just about all of us since the coronavirus went, ah, viral – a combination of worry about catching Covid-19 and the sheer uncertainty that’s underpinned just about every aspect of our lives as a result. In hindsight, rubbing my hands and thinking, “well, I can batter into those delicious shelf-bending doorsteps now” only added an extra tier of pressure to the great uneasiness of 2020.

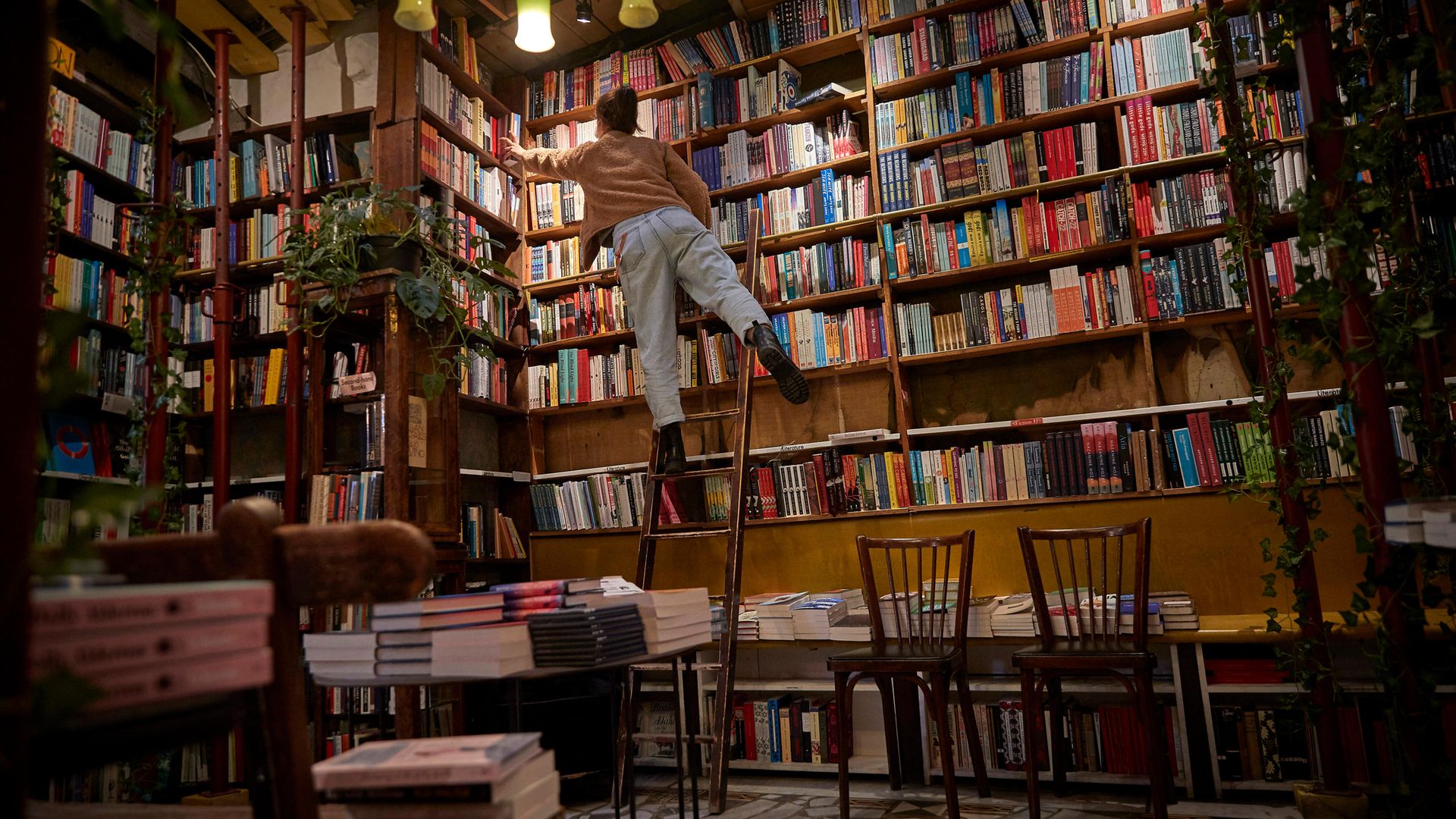

This doesn’t mean we didn’t read at all, of course. Quite the opposite in fact: what could have turned out to be a disastrous year for authors and publishers turned out to be, well, OK really. The closure of bookshops for significant periods hit independent establishments particularly hard and affected backlist sales in general; inability to explore the shelves reducing the chances of stumbling on something unexpectedly alluring. Algorithms can be handy but they’ll never beat the browse.

Despite sales revivals for the suddenly topical A Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe nearly 300 years after it was published and Albert Camus’ erstwhile Outsider also-ran The Plague from 1947, the focus this year more than ever was on new titles, most of them appearing in a thunderous tumble of volumes beginning in October.

This glut of new books has made picking out the best ones of the year a harder task than usual. Despite the herculean efforts of publicists to garner media attention for their titles – often a thankless task at the best of times, let alone this year – it’s almost certain that some absolute crackers will have fallen on stony ground.

This is a blow to authors and readers alike and there will no doubt be some slow burners from 2020 emerging next year. Word of mouth is going to count for a lot: if you’ve really enjoyed a book this year then do tell people. Tweet about it, suggest it for your book club, even contact the author and let them know: a good few writers will be chewing their bottom lip this winter wondering how their book is faring out there among such unprecedented competition.

So, to the books that stood out. One of my fiction highlights came early in the year. Snow, Dog, Foot by Claudio Morandini translated by J. Ockenden (Peirene Press, £12), was published in February, a time so distant now it feels like it was in another geological era. Morandini’s protagonist Adelmo Farandola is a hermit living in a hut on an Alpine mountainside whose many years of solitude have made him irascible enough to shower summer hikers with a hail of stones if they come too close. This is no romantic paean to the solitary life: Adelmo’s is a pretty feral existence. We pass a winter in his company and also that of a ranger who takes an interest in his welfare as well as a scrawny stray dog that attaches itself to the hermit in a contemplative, wise, short and often very funny novel.

The ever-reliable Peirene also produced another of my favourite novels this year in Ankomst by Gohril Gabrielsen, translated by Deborah Dawkin (Peirene Press, £12). When you read an opening line that says, “This is where the world ends. From here there is nothing”, it’s a fair assumption that this isn’t going to be the feelgood novel of the year, but Gabrielsen’s tale of a lone scientific researcher in a remote cabin in the Arctic is a taut psychological thriller with moments of genuine horror in which the polar landscape veers between stark beauty and outright malevolence.

February brought Jenny Offill’s long awaited Weather (Granta, £12.99), shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction. Sometimes, waiting a while for a hotly-anticipated book can produce a deflating anti-climax, but Weather, written in Offill’s characteristically sparse and spaced style which on the page can look like a collection of aphorisms, was an absolute joy. It’s told from the perspective of Lizzie, a Brooklyn woman who works in a library and lives with her partner and young son, and begins assisting her former PhD mentor Sylvia with the reams of correspondence produced by her climate change podcast. Pitting imminent climate catastrophe against the divisions in American society in an everyday world of domestic responsibilities makes for a beautiful piece of work that could even in the long term be the defining novel of the Trump era.

Sarah Moss’ new novel Summerwater (Picador, £14.99) proved to be unintentionally pandemic-relevant, a disparate group of holidaymakers staying in a remote collection of cabins in the Scottish Highlands, devoid of phone signal, each dealing with their own issues in a brilliantly realised collection of interior monologues. Each group or couple is facing its own fractious internal dynamics, not to mention the added stress of sharing a campsite with a bunch of complete strangers. This is practically a study in psychological and social distancing. Like many of Moss’s books, Summerwater takes the temperature of the nation in a thoroughly absorbing manner in a beautifully written book.

One thing all these books so far have in common? Brevity. They’re all under or around 200 pages. I’m sure it’s a coincidence and not a reflection on the restricted coronattention span we’ve developed over the last few months. Probably. By contrast another fictional work to win me over this year was the 750-page hardback collection The Art of the Glimpse: 100 Irish Short Stories edited by Sinéad Gleeson (Head of Zeus , £25). Gleeson has almost single-handedly revolutionised the literary anthology in Ireland with previous volumes drawing together short stories by women in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, but this is a masterpiece of selection and execution. Comprising works by Irish writers of all classes, eras and backgrounds from Bram Stoker to Sally Rooney via Blindboy Boatclub, it’s rare that such a varied collection can hold together as a whole but this one works like a dream to create a wonderful, maybe even definitive book of stories from Ireland.

Other works of fiction that captivated me this year were The Truth Must Dazzle Gradually by Irish author Helen Cullen (Michael Joseph, £14.99), which begins in 2005 with a missing person on the Aran Islands and opens out into a thoroughly moving and frequently funny story of love and compassion; Maaza Mengiste’s Booker-shortlisted The Shadow King (Canongate, £9.99), which brought 1930s Ethiopia vividly to life; and C Pam Zhang’s How Much Of These Hills Is Gold (Virago, £14.99), in which two Chinese-American children look for a place in the world as they cross the vast American landscape of the late 19th century. I had hoped this one would win the Booker as it’s an exquisite novel, but it had to settle for a place on the longlist. No matter, C Pam Zhang is young enough to have several more opportunities yet and I can’t wait to see what’s next.

If fiction proved a valuable escape from this strangest of years there was plenty of good quality non-fiction too. The occasional bolt into the past was certainly worthwhile, notably Martyn Rady’s The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power (Allen Lane, £30). It’s staggering how much of the continent we recognise today is the result of the machinations of one family, much of it inbred and with really weird chins, and Rady manages to condense the story into one pacy and highly readable account of generations of chancers, liars, political masterminds, battlefield heroes and ruthless schemers who shaped Europe for centuries.

For mental flight across the sea in a year in which our wings were clipped like never before, two travel books in particular stood out. In 2017 I was bowled over by Kapka Kassabova’s Border about the land where Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey meet, and this year brought another delve into a part of Europe that many of us know little about. To The Lake: A Balkan Journey of War and Peace (Granta, £14.99) is every bit as good as Border, a personal odyssey into family and regional past and present at the lakeland confluence of North Macedonia, Albania and Greece. Kassabova is a poet as well as a writer, and that keen ear for rhythm and the sound of words helps make this a highly evocative book.

The farther reaches of Europe were also explored in Sophy Roberts’ The Lost Pianos of Siberia (Doubleday, £18.99), in which the author goes in search of the eponymous instruments from crafted 19th century grands to battered old uprights. She’s also looking for the place of the piano in Russian society at all levels and meeting the people who now play them or at least have some connection to them in an original and sensitively written work of travel reportage.

This has been a year of dreadful tragedy. There are many lucky ones who’ve not been directly affected, but the unprecedented conditions have kept so much personal grief out of sight and even endured alone. The sportswriter Ian Ridley lost his traiblazing journalist wife Vikki Orvice to cancer in February 2019 and in The Breath of Sadness: On Love, Grief and Cricket (Floodlit Dreams, £13.99) he charts his attempts to process his loss through a season of watching that year’s County Championship.

It’s a hard book do describe briefly without sounding trite, but Ridley’s is one of the most eloquent, searing, honest and heartfelt accounts of grief you’ll read, yet it’s ultimately a hopeful book. We’ve lost a lot of the routines of life this year, the kinds of things that we’ve come to rely on without thinking, including, for some, the rituals and rhythms of the cricket season. To have suffered personal loss and have those gentle reassurances removed also, as so many are dealing with this year, is almost unbearably cruel, but reading A Breath of Sadness might just help even a little bit as we join Ridley in starting to emerge on the other side.

The ban on spectators attending football matches has had a similar effect on the national game, the removal of that winter routine of buying a programme from the same seller, exchanging cheerful greetings with the turnstile operator and finding your familiar and traditional seat or spot on the terrace. Anyone missing freezing afternoons despairing at yet more hopes and dreams vanishing among the whiff of fried onions, cheap aftershave and Deep Heat could do worse than turn to Harry Pearson’s The Farther Corner: A Sentimental Return to North-East Football (Simon & Schuster, £16.99).

Pearson’s A Far Corner was one of the highlights of the first wave of post-Fever Pitch football books in the 1990s and this diary of a season watching non-league football in the north east of England is warm, very funny and oozes love for the game and its people from every page. You might not actually have been at Ryton & Crawcrook Albion against Brandon United on a cold November afternoon in the Ebac Northern League Division Two, to which Pearson travelled during a train strike that “dragged on like a Garth Crooks question”, and you probably won’t even wish you had been there, but you will identify with the wonderfully-captured experience whatever level of football you watch in non-pandemic times. You’ll pine for the feel of the wind on your face, the disappointment of a weak half-time Bovril , the otherworldly glare of the floodlights and the heaving, breathing match being played out in front of a heaving, breathing crowd.

Brace yourself for a glut of pandemic literature next year – aging white male novelists will no doubt have Very Important Things to say, for a kick-off – but in the meantime you could do worse than relive the bewildering spring of 2020 through the natural world in The Consolation of Nature: Spring in the Time of Coronavirus by Michael McCarthy, Jeremy Mynott and Peter Marren (Hodder Studio, £14.99). The three nature writers, all living in different parts of Britain, record their experiences of the first coronavirus spring in a delightful, contemplative and wise book that brings a new perspective to that strange, unsettling period of the year. If the vaccine news is as good as the noises emerging from the labs, hopefully the coming spring will be an age of rejuvenation and regrowth like we’ve never known before.