CLAUDIA PRITCHARD on a captivating new book in which artist David Hockney and critic Martin Gayford discuss the history of one of humanity’s oldest impulses, to create pictures

As a boy, laughing in the cinema at the antics of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, the artist David Hockney was entertained not only by the gags. He was intrigued by a scene in which the two comics wore heavy great coats but cast strong shadows. Why were they dressed for the winter, he wondered, if the day was so sunny and bright? The dazzling California sun was bringing into British lives an intensity of light that was unknown in his native Bradford.

Small wonder, perhaps, that Hockney settled in California in his late twenties, although he now resides in Normandy, his enthusiasm for nature undimmed.

His fascination with light and its role in art is one of the themes that runs through his extended conversation with writer and critic Martin Gayford, recorded in an updated edition of A History of Pictures.

The title is important. This is not a history of art, but emphatically the story of mankind’s instinct to depict the world around, using the available media of the day. The instinct is evident from early cave art to Hockney’s own experiments with drawing on an iPad.

Not every picture qualifies: photography is given a partial welcome, not least as an aid to painters, but, says Hockney: ‘We don’t have to view the world in the way a lens does; two human eyes and a brain do not naturally see in that way.’

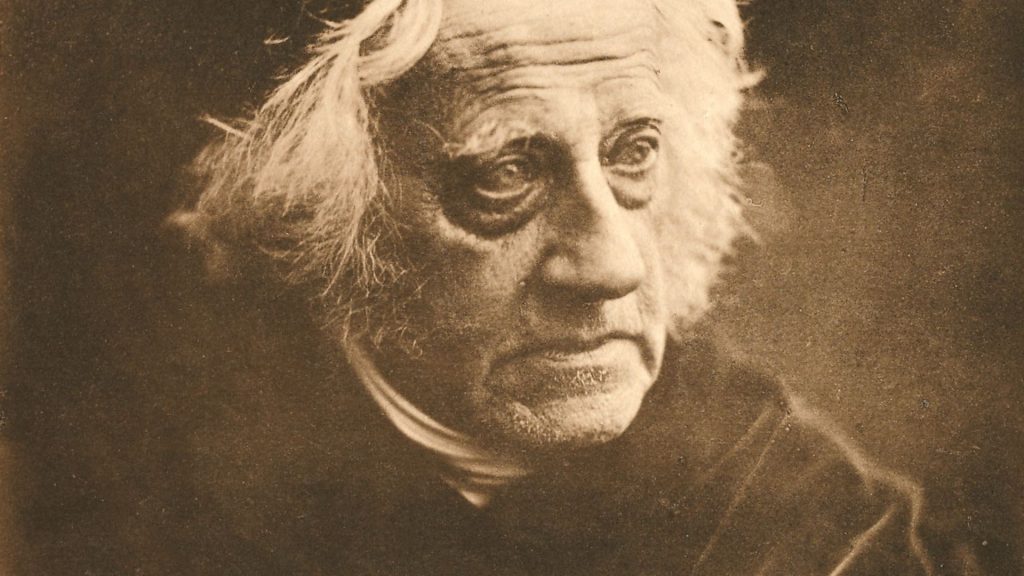

Yet the word pictures is widely adopted. Those childhood cinema trips were to ‘the pictures’. When the scientist John Herschel reported to his friend William Henry Fox Talbot on the first daguerreotypes in 1839, it was of a new type of picture that he wrote.

In their journey through depictions of our world, Hockney and Gayford stop off at a succession of masterpieces in this abundantly illustrated volume.

There are stars aplenty from the most-visited galleries in the West, among them Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), with its shaft of light over the shoulder of – probably – Giovanni di Nicolao di Arnolfini, an Italian merchant working in Bruges, and its absorbing props.

Each has with its own texture and demands for technique: a pair of wooden pattens, a dog, a convex mirror, velvet.

The composition (much imitated on social media during lockdown by couples at a loose end) is part of the national consciousness. These stars of the National Gallery, even while it is closed, are printed in the memory.

Says Hockney: ‘The Arnolfini Portrait is just a view of two people in a room, but it comes up in my mind like a slide. There are millions and millions of pictures of a couple of people in a room, but most of them are completely forgettable and consequently they disappear.’

Van Eyck was a master at illuminating his scenes. A century and a half later, the raffish Caravaggio would dramatically develop the bright light and deep shadow of chiaroscuro to which successive generations of artists would aspire. But this particular display of virtuosity, as demonstrated in Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599), is shaken off by later young bloods turning to other traditions for their inspiration.

Hockney observes that around 1870 European artists looked to Japan, to escape the long shadows of Renaissance perspective and to photography, which was growing in popularity and dexterity.

‘At the beginning of the 19th century all European paintings were done with a lot of chiaroscuro,’ says Hockney. ‘By the end of the century shadows had gone from a lot of paintings. There are no shadows in Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, nor in Gauguin, nor Bonnard.’

Gayford compares Gauguin’s radical compositions in which figures in the distance are prominent and perspectival rules are ignored with the mid- 19th-century woodcuts of Utagawa Hiroshige. In Hiroshige’s View of the Harbour, vessels at sea are as dominant as those at the quayside.

What artists could do on canvas by way of bringing the background forward has not been so easily achieved in photography and film with their single focal point. But Gayford explains the innovative techniques at work in Citizen Kane (1941), which kept in focus even tiny figures in the far distance, as a Renaissance artist could do.

Hockney has argued for years that painters were much more reliant on optical aids than the romantic imagination allows, and he explained their devices in his book Secret Knowledge, published in 2001. ‘I think Caravaggio, for example, made his pictures by a form of drawing with a camera. His paintings are a kind of collage of different projections,’ he says. Gayford agrees: ‘Caravaggio posed each model – like an actor in a play – and painted them more or less precisely as he saw them.’

Not only composition but colour choices were influenced by the use of lenses. ‘Vermeer had a lens of very good clear glass – meaning the green tints had gone, so the reds, blues and yellows would have looked really beautiful.’

He likens the precisely observed The Little Street (c1658) to an imagined colour photograph of a 17th-century Dutch townscape.

These amiable conversationalists are in love with the whole process of mark-making, over and above the reproductive capacities of photography, or digital art, even though Hockney has experimented enthusiastically with his iPad. To his mind, this medium counts as drawing, because the hand is involved.

‘Drawings made on a touchscreen are still made by hand,’ agrees Gayford. ‘The app used to make them is just another tool like a brush, or an easel, or the burnt wood that the prehistoric artist chewed up and softly blew around her or his hand.’ Hockney attributes the popularity of Van Gogh partly to his visible brushstrokes, the gesture taking us closer to the man.

Talking before the current world shift, but with uncanny prescience, in the final chapter these two wise men imagine where this history goes next.

‘Everything is going to be so different in the future, in ways we can’t know,’ says Hockney. ‘Now you can live in a virtual world if you want to, and perhaps that’s where most people are going to finish up – in a world of pictures.’

A History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer Screen by David Hockney and Martin Gayford is published by Thames and Hudson at £19.95