CHARLIE CONNELLY on two new European novels which highlight the underappreciated artistry of translators

The job of a literary translator can be a thankless one. It’s a multiskilled calling with two main demands: fluency in at least one other language that isn’t your own and an exceptional talent for writing. It’s a role requiring immense artistic empathy, putting oneself inside the mind, motivations and technique of another writer to create something as fluent and nuanced as the original work.

A good translator hears and feels the rhythms and undulations of another person’s prose in another person’s language and is able to render them in language at least as good as the original. A good translator is also practically invisible.

You don’t get into literary translation for the glory, that’s for sure. Like that other chimerical presence in the world of books the ghostwriter, the translator is destined always to remain on the fringes and in the shadows.

While publishers and reviewers are much more careful about crediting translators than they used to be and the Man International Booker Prize splits its £50,000 cash award equally between author and translator, the person rendering great works of literature into another language still remains largely anonymous.

When translators do break out of a small-font namecheck on a title page it’s not often to be chaired shoulder high through the streets, either. Most recently the selection of Marieke Lucas Rijneveld to take on the Dutch translation of Amanda Gorman’s The Hill We Climb, the poem she performed at Joe Biden’s US presidential inauguration in January, drew protests that a white non-binary person was the wrong choice to tackle a work inspired by the lived experience of a young black woman.

Rijneveld, who won last year’s Man International Booker Prize for their novel The Discomfort of Evening, withdrew from the assignment.

Yet despite the lack of recognition and the fact it’s not exactly a profession you’d choose in order to get rich, there are some quite brilliant literary translators at work today. Indeed, thanks to them and the persistence of publishers, mainstream and specialist, in commissioning high quality English language renditions of books written in other languages, we find ourselves currently in a golden age of translation. Two books published this month present fine examples of why this is the case.

Jamie Bulloch has been a prolific and versatile translator from German to English over the last decade or so, producing more than 30 books ranging from Robert Menasse’s EU bureaucracy satire The Capital to footballer Mesut Özil’s autobiography Gunning For Glory.

His latest collaboration is with Daniela Krien, one of Germany’s leading contemporary novelists, on Love in Five Acts, published this month. It’s the story of five Leipzig women, Paula, Judith, Bride, Malika and Jorinde, whose lives intertwine either substantially or tangentially in a beautiful novel of what it is to be a woman in modern Europe and an illustration of how what we understand to be ‘freedom’ can be as much constricting as liberating.

Reading each woman’s story, we see differing lives and situations united by division: relationship schisms and generational conflicts, whispers and secrets, the damage caused by unrealistic expectations and futures left uncertain and unfulfilled.

There’s Paula, who lost a baby to sudden infant death syndrome. She’s married to Ludger, an architect and environmentalist who only becomes animated first when talking about his work, and then when their first child Leni is born. Paula becomes increasingly isolated, struggling to find her space in the world, and as a mother feels alienated even from her own body where, “the breasts belonged to Leni, the limbs were heavy, the hair lifeless and her belly took ages to return to its own shape”.

The narrative moves from Paula to her closest friend Judith, skimming through dating apps and meeting men for meaningless sexual encounters. She’s a doctor, a good one, working long hours and finding true release only when grooming and riding her horse. She seeks male company but finds the intimacy of familiarity unfulfilling, ultimately rejecting it. “Every time a man took off his shoes and lay on this sofa it was over. It was the moment that signalled the end of all the effort, the moment she was captured.”

She is having a long-term affair with her married former boss, a relationship that’s part of a pattern: her first boyfriend had been her school PE teacher, a married man twice her age, then when she commenced her studies at medical school she began an affair with the professor who gave the first lecture she attended.

Brida is a frustrated novelist separated from but still close to the father of her children. When he meets someone else, a woman who has “won him over with her younger body that hasn’t borne any children… a body that knows only exercise and healthy food”, everything is done very reasonably, the three of them even sharing holidays with the children. On top of this unusual domestic arrangement, Brida finds it almost impossible to combine her life as a mother with her career as a novelist.

Never has Cyril Connolly’s pronouncement that “there is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hallway” seemed so apposite. When Brida’s first novel is published and it finally seems she is going to find her own way, when she finally felt she belonged somewhere, she discovers she is pregnant again.

Malika is a violinist whose parents had been at the centre of the cultural milieu in the GDR. She grew up listening in to their soirees with writers, musicians and artists, the family home bursting with ideas and creativity. After reunification these cultural gunslingers became less notable, less important, and rely on their children to provide their artistic cachet.

Malika’s mother has resented her since the day she was supposed to audition for a prestigious music college but deliberately smashed her violin bow in an argument over practice. She’s also been in the shadow of her sister Jorinde, who became an actor well-known on the television while Malika became ‘just’ a music teacher.

Second in her mother’s estimation Malika eventually becomes second in her boyfriend’s estimation too, until in the final section of the novel, based on the story of Jorinde, Malika finally finds a role she can fulfil in accepting a life arrangement arguably more unconventional than Brida’s curious ménage à trois.

Krien is a child of the east, born and raised in Jena in the German Democratic Republic and has lived in Leipzig since the turn of the millennium. She was 14 when the Berlin Wall came down and the post-war division of Germany haunts the characters of her novel in a more subtle way than her 2011 debut, translated into English again by Bulloch as Someday We’ll Tell Each Other Everything and set just after reunification.

Germany’s complicated internal reabsorption is always in the background of Love in Five Acts, a hairline fracture in the country that contributes to the frustrations in the women’s lives, making relationships brittle when early idealism and hoped for opportunity is gradually extinguished. It wasn’t meant to be like this, this freedom stoking the thrumming ennui of these five women’s stories.

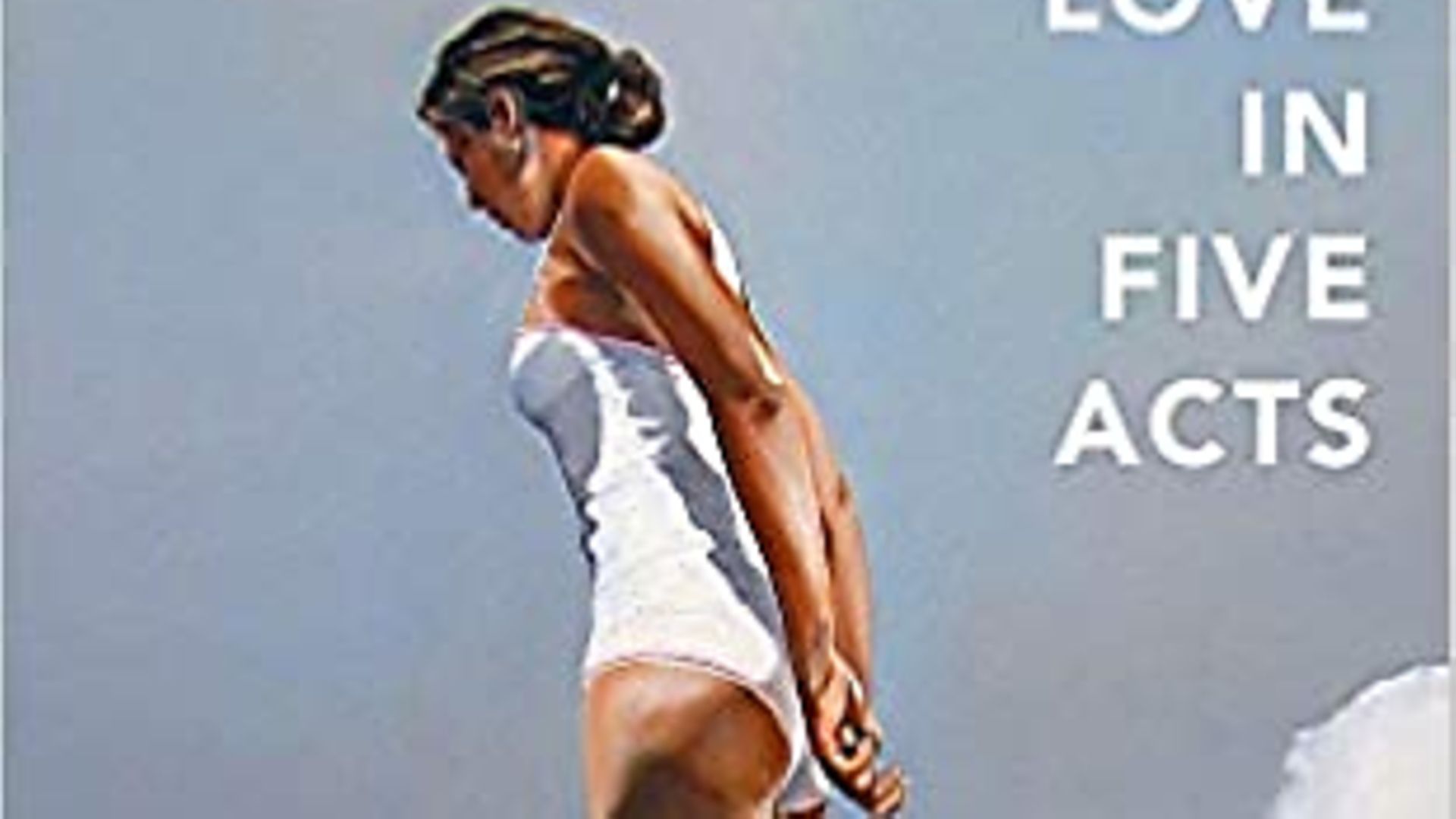

Love in Five Acts is written – and translated – sparsely, five disparate voices cramming a world of nuance into a rare and elegant conciseness. The book’s production is equally elegant, most notably in its arresting cover image by American photorealist artist Eric Zener of a woman on a diving board looking uneasily into the void, a background of clouds giving the impression she’s high in the sky.

Maylis de Kerangal’s new novel Painting Time is a different proposition. It’s the third collaboration between the author and translator Jessica Moore, a Canadian poet, and the intimacy of experience that exists between the two contributes significantly to an absorbing read. De Kerangal writes in long, sweeping sentences dense with description and Moore preserves this in her translation, drawing the reader into intricate detail that’s never a slog to negotiate.

De Kerangal, from Le Havre, is probably best known for her 2014 novel Réparer les vivants, translated into English by Moore as Mend the Living. Set over the course of 24 hours, the novel chronicles the transplant of a 19-year-old man’s heart into a middle-aged woman through the experiences of everyone affected.

In Painting Time, de Kerangal’s characteristically intense literary focus centres on Parisian Paula Karst, who enrols in an apprenticeship in decorative art at a prestigious institution in Brussels.

The course only lasts a few months and is the making of Paula, who becomes close to both her flatmate Jonas and a fellow student, tattooed Glaswegian nightclub bouncer Kate. The study is hard, the work incredibly detailed trompe l’oeil for interiors, making concrete look like wood and wood look like marble, pulling off brilliant deceptions where “trompe l’oeil has to make us see at the same time it obscures”.

Paula obsesses over her work. When painting a tortoiseshell design she throws herself into the life and science of the hawksbill sea turtle of the Caribbean Sea and has her hair highlighted to a shade called ‘tortoiseshell’.

“The stars are crazy for it,” says the hairdresser, “Julia Roberts, Sarah Jessica Parker, Blake Lively”, the names blundering intrusively from the outside world into Paula’s hyper-focus as if from another galaxy. When she works on reproducing Cerfontaine marble and visits the quarry, de Kerangal composes a beautiful passage on the Beauchateau cliff from which the marble comes, bringing it to life in both its geology and humanity, imagining men on rickety ladders chipping away at the exquisitely veined rock from the end of the 18th century.

Paula and her two closest friends mimic their craft in their personal relationships, seeing everything while seeing nothing, their lives as much of a deceptive veneer as their work. Paula soon misses the cloistered intimacy of the course, where she, Jonas and Kate became so close as to almost be living one life. It’s just a particular version of life but for Paula nothing can replace that brief feeling of belonging.

She takes a job at the Cinecittà film studios in Rome, working as a set dresser on sound stages where whole worlds are created in a confined space, conditions in which she begins to feel comfortable. Paula leaves no trace of herself outside of her work – when she moves from Rome back to Paris “it takes only seconds to liquidate her Italian life” – and only begins to emerge from claustrophobic introversion when she travels to the Dordogne to work on a replica of the caves of Lascaux, reproducing the palaeolithic paintings of artists who lived 20,000 years ago.

What unites these two novels by two of Europe’s best contemporary novelists is the global pandemic that can’t be conquered by a vaccine – loneliness. These characters are surrounded by people yet ultimately alone, each seeking to belong, to find their place, from the challenges of parenting in a unified Germany to communicating with ancient peoples through a finely tipped paintbrush.

The books are also united by their excellent translations, pulled off with sensitivity, empathy and some beautiful writing. In Mend the Living de Kerangal made Claire, the beneficiary of the heart transplant, a translator. “For me she couldn’t have been anything but a translator because translators keep within their language room for another,” she said. “They can give hospitality to other languages.”

Love in Five Acts by Daniela Krien, translated by Jamie Bulloch, is published by MacLehose Press, price £14.99. Painting Time by Maylis de Kerangal, translated by Jessica Moore, is also published by MacLehose Press, price £16.99

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

FIVE GREAT BOOKS OF NEW TRANSLATED FICTION FROM EUROPE

THE PEAR FIELD

Nana Ekvtimishvili, trans. Elizabeth Heighway (Peirene Press, £12)

This Georgian novel from the excellent Peirene Press has been longlisted for this year’s Man International Booker Prize. In Lela, Ekvtimishvili has created an extraordinary character from a disadvantaged background determined to escape her apparent destiny, make the best of herself and do her best for a similarly disadvantaged friend. A gem.

BLIND MAN

Mitja Čander, trans. Rawley Grau (Istros Books, £9.99)

This story of a visually-impaired book editor drawn into politics and seduced by ambition and the corruption of power is an insightful satire on contemporary Slovenia and by extension the world of politics and the media beyond. It transcends borders with its topical resonance.

CIVILISATIONS

Laurent Binet, trans. Sam Taylor (Harvill Secker, £14.99)

Novels that present an alternative version of history can be hit or miss, but if anyone can pull it off it’s Laurent Binet. In Civilisations Columbus fails to make it across the Atlantic and instead the Inca leader Atahualpa leads a successful invasion of Europe, becoming Holy Roman Emperor. Another highly ambitious work from the author of HHhH.

THE FACES

Tove Ditlevsen, trans. Tiina Nunnally (Penguin Modern Classics, £8.99)

Ditlevsen is undergoing a deserved resurgence with the republication of her extraordinary Copenhagen Trilogy of memoirs earlier this year, and this story of a Danish children’s author trapped in an awful marriage contemplating insanity is a concisely-written classic of modern Scandinavian literature.

IN MEMORY OF MEMORY

Maria Stepanova, trans. Sarah Dugdale (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99)

Part fiction, part memoir, part travelogue, Stepanova’s book prompted by her sorting of documents and photographs left behind after the death of an elderly aunt is a passionate, thoughtful and deeply rewarding read with much to say on the story of Europe’s 20th century.