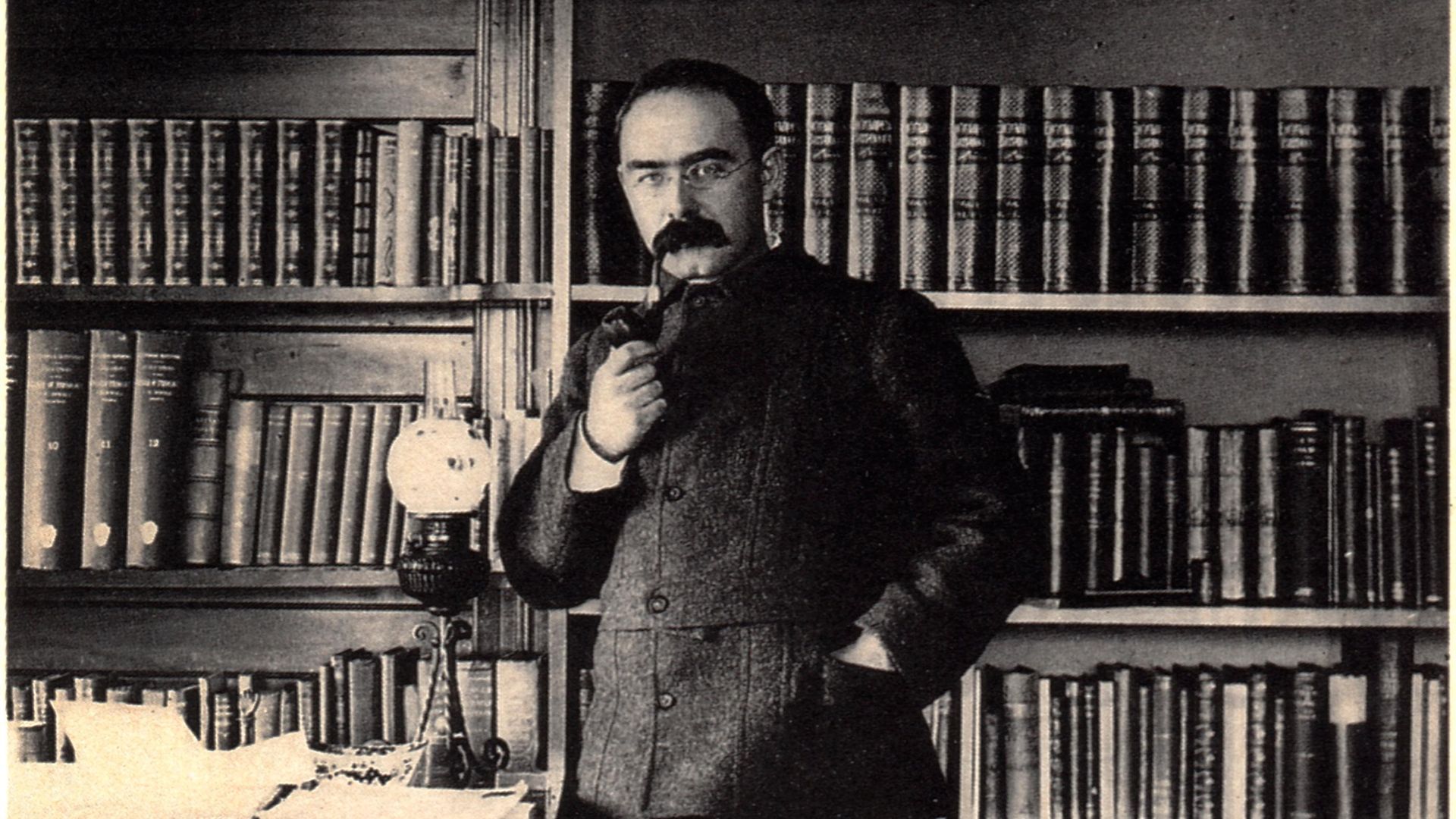

Jonathan Sale on the centenary of a courtroom drama centred on Rudyard Kipling’s celebrated poem, If, and the continuing power of the very iffy word itself.

If – and it’s a big if – I’m any judge of groundbreaking literary cases, this month sees the centenary of a wonderful example of poetic justice in action: Rudyard Kipling v. Sanatogen Tonic. “INSULTING A POET” was how the Pall Mall Gazette described the unpoetic courtroom drama over the illicit use of four lines of his famous If. It was a clear case of “Kipling poem quoted in advertisement” shock horror in December 1920 when the Nobel Prizewinning author sued over this flagrant breach of copyright.

The relevant law permitted quotation for research, criticism or private study but did not mention advertising, let alone that of “the miserable claptrap of a patent medicine vendor”. Kipling had not granted Sanatogen a poetic licence. No money-grubber, he had asked for a payment of £100 to be given to the charity of his choice, plus a promise to cease from taking his verse in vain. The offer had been refused by the manufacturers.

The advertisement began innocently enough with a quote from Buddha about subduing disease by willpower. Unfortunately for the defendants, it wasn’t the Enlightened One but the no-nonsense author of The Jungle Book who consulted m’learned friends. The makers of Sanatogen were alleged to have used in their advertisements a moving section beginning “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew…” The verse went on to urge the reader faced with an uphill struggle to keep going with a strength of will that enabled him to say to himself “Hold on” – and, presumably, take a hefty swig of the tonic.

The defence could not deny that they had used the lines in question. However, continued their counsel, the passage fitted in happily with the subject matter being advertised and so they were a legitimate user. He called in evidence the late Lord Tennyson, making the point that Kipling had lifted some of his lordship’s lines as prefaces for a short story. Similarly, Kipling had quoted from Knocked ‘em in the Old Kent Road without, as far as anyone in court knew, asking permission from Albert Chevalier, who had penned them.

“Hold on,” Kipling would have said if he had been giving evidence in person. As he had put it in lines further down the poem which were not quoted in court, it was really tough “to hear the truth you’ve spoken/Twisted by knaves to make a trap for fools”. Where he might have had an emotional difference from his own poem was while waiting for the verdict. His verse may have declared that “You can meet with Triumph and Disaster/And treat those two imposters just the same,” but in fact he could well have permitted himself to feel that Triumph was not such an imposter after all.

Fortunately for the poet’s peace of mind, Mr Justice Peterson of the Chancery Division gave the judgement that a poem should not be diverted into promoting a product and that there had been a breach of copyright. He granted an injunction against further repetition and ordered the defendants to pay costs plus nominal damages of £2.

Meanwhile, the Sanatogen executives would have done well to heed an early line: “If you can think” (they clearly didn’t) “and not make thoughts your aim” (i.e. taken the speedy action of making the charitable donation in the first place) they would have been able to “keep your head when all about you /Are losing theirs and blaming it on you.”

In the ensuing century since its legal victory, the poem has triumphed again, not least by being voted the nation’s favourite and inscribed above the players’ entrance at Wimbledon. It is echoed by the title of the satirical film if… which I saw screened in France though forget if it was called Si. And then there’s Steve Bell’s strip cartoon of the same name in the Guardian.

If has, of course, its iffy moments, such as the last words: “You’ll be a Man, my son!” It’s a pity that the scansion is wrong for “You’ll be a Woman, my daughter!”

Kipling’s poem aside, where the word ‘if’ gets iffy is in its use as a get-out-of-jail card. O.J. Simpson’s “If I did It” was interpreted as a way of saying “I did It” without confessing. I personally would like to sue any politician who uses “if” instead of “that”. A very recent offender was the Polish minister who apologised – via a non-apology – for the near-total ban on abortion: “I’m sorry if anyone was offended.” There is absolutely no doubt that many Poles were offended. Offended citizens were packing the streets to protest, despite being beaten up by police.

The most sneaky misuse of this weasel word is more complicated and less common – but still worthy of being slapped with an injunction. People who should know better write “if” at the start of a sentence when they mean “and” halfway through it. If I may explain…. Suppose someone is comparing two prime ministers. Instead of saying, “Boris Johnson went to Eton and John Major went to a state school,” they are liable to come up with the erroneous “If Johnson went to Eton, Major went to a state school.” There is in fact no if about it. The two do not depend on each other at all. Major went to a state school whichever expensive establishment Daddy Johnson sent Junior Johnson to. This type of misuse should be met with the full rigour of the grammar police. If I may say so.

If’s inspiration

If is written in the form of paternal advice to Kipling’s son John, who was killed at the Battle of Loo, in 1915, just five years after it was published. The poem was inspired by the character of Leander Starr Jameson, a British colonial administrator who lead the failed ‘Jameson Raid’ to overthrow the Boer government of the Transvaal Republic. Kipling was a friend of Jameson and was introduced to him, so scholars believe, by another colonial friend and adventurer, Cecil Rhodes, who supported the raid.

Jamieson was was sentenced to 15 months for leading the operation, and the Transvaal government was paid compensation by the British South Africa Company, while Rhodes was forced to step down as premier of the Cape Colony. The raid had had the sympathy and tacit support of the British government, but Jameson never revealed the extent of this. The lines in the poem – “If you can keep your head when all about you / Are losing theirs and blaming it on you” – are said to be a specific tribute to Jameson’s silence.