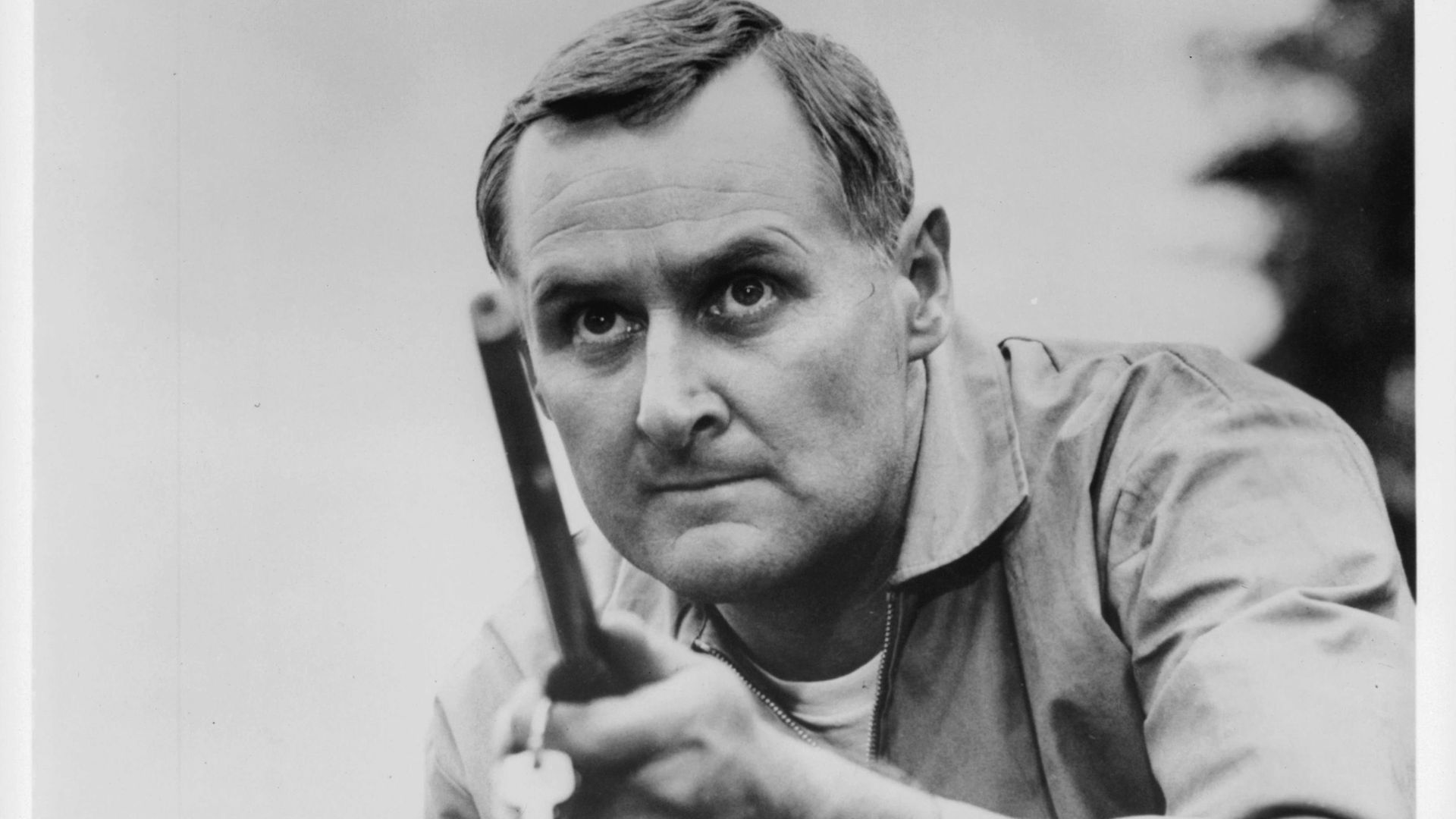

Best known as Grouty in Porridge, Peter Vaughan was an actor who seemed to get better with age

The Seven Ages of Man speech in Shakespeare’s As You Like It amounts to a career trajectory for all serious actors. The best and luckiest manage to grow old with their audiences, going from playing “the whining schoolboy, with his satchel,” to youthful lovers “sighing like furnace,” and, finally, they get to portray the “second childishness and mere oblivion” of characters in advanced old age.

Peter Vaughan – best known perhaps at Grouty in the television series Porridge – was 84 when I got to meet him and he was making a big success of the Seventh Age. He was promoting a film directed by Frank Oz called Death at a Funeral, which was, in all honesty, hardly his greatest work, but it was work and work is what has always mattered in the acting profession.

I’d lunched with Vaughan’s fellow octogenarian Sir Christopher Lee not long before and he confided in me how irked he had been not to have bagged the part of Mr Stevens Snr, the father of Sir Anthony Hopkins’ repressed butler in The Remains of the Day. Of course, it’s hard now to imagine anyone but Vaughan playing that flinty-eyed old butler, but he conceded it was a fight to get it.

“There are unfortunately a lot of us old guys around,” Vaughan said. “These old codger roles are always scene-stealers and they can define entire careers, so the stakes are high. Actors vying for them are conscious, too, that their time is running out.”

It’s not hard to see why the director James Ivory cast Vaughan as Mr Stevens Snr as that old-school professional, determined to ensure that “everything is in hand,” was not unlike the actor. There was a scene in the film in which a droplet of water fell from his nose into a bowl of soup that he was serving. Vaughan thought nothing of having a painful solution put up his nostril that caused the required droplet to fall precisely on cue. He didn’t even think to ask if it would do him any harm.

Even in comedies, such as the film he was promoting, Vaughan approached the work with deadly seriousness. He said that, while making the thriller Straw Dogs, the director Sam Peckinpah had told him he never wanted to see his actors laughing at each other “because when they are conscious that they are funny they cease to be funny.” He said that he and his wife Lillias had been appalled to see a play in which the actors had broke out into uncontrollable laughter. “It was,” he said coldly, “unprofessional and theatre tickets don’t come cheap.”

Vaughan’s big break had been playing the homosexual character Ed in Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mr Sloane at Wyndham’s Theatre in 1964. It was a brave part at that time, but Vaughan could see the impact it would have. He also liked Orton. “Joe was a one-off. He would always wear army boots, a Chairman Mao jacket and an old War Department gas mask over his shoulder in which he had his meat pie for lunch and his copy of the script. If I asked him about a line, he’d tell me it means whatever I want it to mean. Harold Pinter would say the same thing, and, years later, when I was making the film The Crucible, so did Arthur Miller.”

One critic noted that Vaughan could convey menace reading a weather report. He accepts his “bloody awful war” was probably a factor in how he came across. He served in Normandy and Belgium, as an officer, which he said was “terrifying”. Later, in the Far East, he was at the liberation of Changi jail. “It was a strange way, between the ages of 18 and 24, to form a character,” he said. “I think I was in a daze when I came back to Britain, after seeing what I saw. It took me a while to come to terms with it.”

His first marriage to the actress Billie Whitelaw didn’t last, he reckoned, as he hadn’t been good at communicating emotions. He’d learnt to be “a lot more human” when he married, not long after he parted with Whitelaw in 1966, Lillias Walker, also an actress. That union lasted until his death in 2016 at the age of 93.

He was working until the very end – his final role was as Maester Aemon in Game of Thrones – and I well remember him scoffing when I mentioned the word “retirement”. This is no time to take it easy – I am in my prime,” he said, quite seriously.