RICHARD LUCK on a forgotten chapter in tennis history and the man who became the unexpected beneficiary of the Grand Slam glory at SW19.

This year’s Wimbledon marks 50 years since the start of the Open Era, when the four grand slam tournaments finally agreed that professionals could compete with amateurs, so ending a split that had divided the sport since the 1800s.

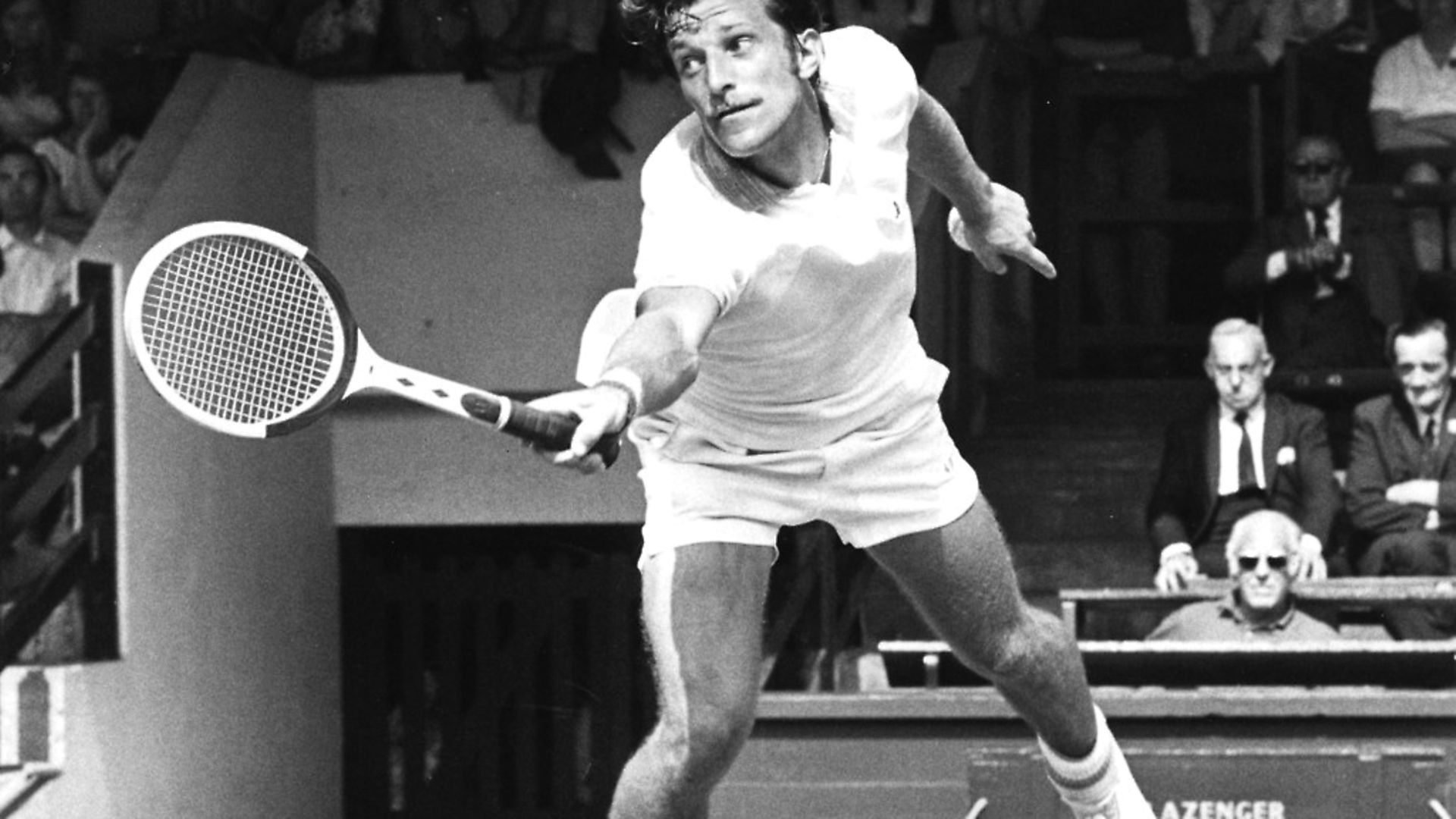

We can expect much talk of how the game has changed in the last half century, and of the great Wimbledon champions we have seen in that time. But what we probably won’t hear much about is the first European to win the championships in the Open Era. And that is a pity, because Jan Kodes, the Czechoslovakian who lifted the cup in 1973, did so at the end of the most bizarre Wimbledon’s men’s tournament ever staged.

Born in Prague in 1946, Kodes came to prominence on clay, winning the French Open in 1970 against Yugoslav Željko Franulovic. He would return to Roland Garros the following year and retain his title defeating Romanian maverick Ilie ‘Nasty’ Nastase over four, hard-fought sets. 1971 also saw Kodes reach the final of the US Open, a feat he’d repeat in 1973. Back then, the US event was held not on the hard courts of Flushing Meadows but on the beautifully cultivated lawns at Forest Hills.

Not that Kodes had a lot of time for this type of tennis – when asked by interviewers what he thought of the surface, the taciturn Czech responded that ‘grass is only for cows’.

Although an established name with a versatile game, Kodes didn’t come to Wimbledon 1973 with the highest of expectations. The No.15 seed, the players ranked above him read like a Who’s Who of tennis greats. Defending champion Stan Smith, Nastase, Arthur Ashe, John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, Roy Emerson, Tom Okker – Kodes would have his work cut out for him if he was to win his first major on grass. It was then that the name of another European tennis player hit the headlines. And the story he had to tell would throw the All England Championships into chaos.

Nikola Pilic? had been a fixture on the international tennis circuit since the 1960s. With a US Open men’s doubles win comprising his greatest claim to fame pre-Wimbledon 1973, Pilic was playing the best tennis of his life in the run-up to the tournament. Having reached the final of the French Open, the talented Yugoslav looked set to improve on his previous best at Wimbledon, a 1967 semi-final defeat at the hands of Aussie legend John Newcombe. Whatever dreams Pilic harboured, they were to be punctured not by an opponent but by his own national tennis federation.

As for how and why Nikola Pilic came to be pulled from Wimbledon 1973, we’ll let the great Jimmy Connors take up the story: ‘It wasn’t clear whether he had refused to play in a Davis Cup tie [against New Zealand in May 1973] or wasn’t allowed to play, but the consequences were that his national authority suspended him. The International Lawn Tennis Federation backed the decision and Pilic was dropped from the Wimbledon draw. In protest, most of the ATP members withdrew from the tournament, leaving just a few top players like Nastase, Jan Kodes and Roger Taylor of England.’

Connors is underselling it with regard to player withdrawals. In total, *81* members of the ATP refused to compete at Wimbledon, among them 13 of the 16 seeds. Smith, Ashe, Rosewall, Newcombe; each gave up their shot of glory in support of – in their eyes, at least – an unfairly treated fellow pro.

Of course, boycotts were all the rage in the 1970s. In sporting circles they invariably involved South Africa and its apartheid regime. Wimbledon, meanwhile, had experienced a few walkouts in 1972 due to squabbling between the various players’ organisations. However, the 1973 farrago was on an unprecedented scale and threatened to turn the world’s most prestigious tennis tournament into a joke.

It wasn’t bad news for everyone, mind you. If you were a British male tennis player, the boycott was an absolute boon. A total of 16 home professionals were entered in the draw, among them such not-even-famous-in-their-own-household names as Phil Siviter and Clay Iles. Naturally, with it being the 1970s, David and John Lloyd were there as was the marvellously monikered John Feaver. And then there was local favourite Roger Taylor, a two-time US Open doubles champ and erstwhile world No.8 whose route to the semi-finals included a five-set epic against a shy 17-year-old Swede by the name of Bjorn Borg.

The ‘Ice Borg’ was one of several young players who enjoyed a decent Wimbledon that year. Connors and Vijay Amritraj (21 and 20 respectively) both made it to the quarter-finals and America’s Sandy Mayer (also 21) reached the only Grand Slam semi of his career. Then, at the other end of the spectrum, there was Australian veteran Owen Davidson whose generous seeding provided the nearly man of the 1960s with a well-deserved last hurrah.

And there, in amongst all the qualifiers and the lucky losers, was Jan Kodes, overcoming unknowns like Japan’s Kenichi Harai and Italy’s Pietro Marzano in the early rounds before seeing off South African doubles specialist John Yuill and ageing Indian journeyman Jaidip Mukerjea.

Amrtitraj was Kodes’ next victim, the sapping five-setter paving the way to a semi-final clash with home favourite Taylor. Those keen to know how the crowd felt when that one went the distance before going the way of the Czech need only consult anyone who sat through all three days of Tim Henman v Goran Ivaniševic.

And then it came to pass that, on Sunday July 8, Czechoslovakia’s Jan Kodes walked out on Centre Court to face the Soviet Union’s Alex Metreveli. Born in Tbilisi, Metreveli (then 29) had the edge on the experience front over Kodes (27) and while he couldn’t match the Czech’s Grand Slam success, he’d reached the semi-finals of the Australian and French Opens the previous year. Somehow, against all the odds, a Wimbledon that looked like it might become a lottery was set to produce a champion worthy of the title.

In a tournament peppered with new faces, it was perhaps appropriate that the 1973 final hinged on a different kind of newcomer. Tennis had been experimenting with the tie-break format since the mid-1960s but it wasn’t until 1973 that it arrived in SW19.

With Kodes leading by a set but the players inseparable at 8-8 in the second, the tie-break came into operation and provided the dramatic high point of the contest. When the Czech came out on top 7-5, it was pretty clear that he’d go on to take the title. When match point was finally won, Kodes skipped over the net and hugged his opponent. To see photos of him with the Wimbledon Cup is to look upon a man whose delight at winning isn’t in the least bit diminished by the Pilic affair.

And while there are those who’ll continue to put an asterisk next to Kodes’ Wimbledon win, tennis itself has nothing but the highest regard for the player, inducting him into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1990.

As for the supporting player in this story, Nikola Pilic, he’d shake off the disappointment of missing Wimbledon to reach the quarter-finals of the 1973 US Open. Determined to put the Davis Cup business behind him, he’d continue to play at a high level until 1978, finally retiring at the age of 39. In a lip-smacking turn of fate, Pilic would go on to coach three different nations to Davis Cup titles – Germany (1988, 1989 and 1993), Croatia (2005) and Serbia (2010) – a feat unique in the history of the competition. Add to this the role Pilic’s academy played in nurturing Novak Djokovic and this proud son of Split no more deserves to languish in the footnotes of sporting history than Jan Kodes, the first European to win Wimbledon after tennis Open-ed for business.