PETER TRUDGILL on the sometimes surprising languages spoken by some our greatest composers.

Music is sometimes said to be the universal language; and it is certainly true that the music of the great classical composers is as well known these days in China, South Korea and Japan as it is in its original European homeland.

But the languages which the composers themselves actually spoke are not often thought of as being an interesting or important topic. Surely it is all pretty straightforward? Tchaikovsky was a Russian, so he must have been a Russian speaker; Grieg was Norwegian and therefore, obviously, his mother tongue was Norwegian.

Often, however, the facts are actually not so mundane. Anyone with an interest in symphonic music knows that Sibelius was Finnish. In fact, he is one of Finland’s great national heroes. But it would be a mistake to suppose that because of that his native language was Finnish. Jean Sibelius, as he chose to be known, was originally named Johan Julius Christian Sibelius and was born into a Swedish-speaking family who called him ‘Janne’.

Finland is officially a bilingual country, with both Finnish and Swedish as official languages. Ninety percent of the population are Finnish-speakers, but there are two major areas of Finland which have been predominantly Swedish speaking for many centuries, one on the south coast, and one on the west coast. Also, the autonomous Åland Islands off the southwest coast of Finland are almost entirely Swedish speaking. From the age of nine, though, Sibelius went to a Finnish-medium school so his Finnish did become fluent, even if he was not always too confident about it.

Fryderyk Szopen was also bilingual, in his case in Polish and French. He is more usually known by the French version of his name, Frédéric Chopin, but he was born in Zelazowa Wola, in Poland, and lived there until he was 20. He grew up speaking French as well as Polish because, although his mother was Polish, his father was French.

Fryderyk/Frédéric was proficient in both languages, and could write both well. When he died at the young age of 39, he was buried in Paris, where he had spent most of his adult life and had risen to international fame, but his heart was taken back to Poland where it is still interred at the Bazylika Swietego Krzyza, or Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw.

In contrast, the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg was a bit disappointing on the bilingualism front. His great-grandfather was Alexander Greig, who came from Aberdeen. (Norwegians pronounce the re-spelt version of the name as ‘Grigg’.) The family maintained their links to Britain for several generations – Grieg’s godmother was a Mary Stirling from Stirling, and his father, also called Alexander, made frequent business trips to London.

Grieg himself, however, did not speak English at all well, although it is said to have improved in later life after a number of visits to England.

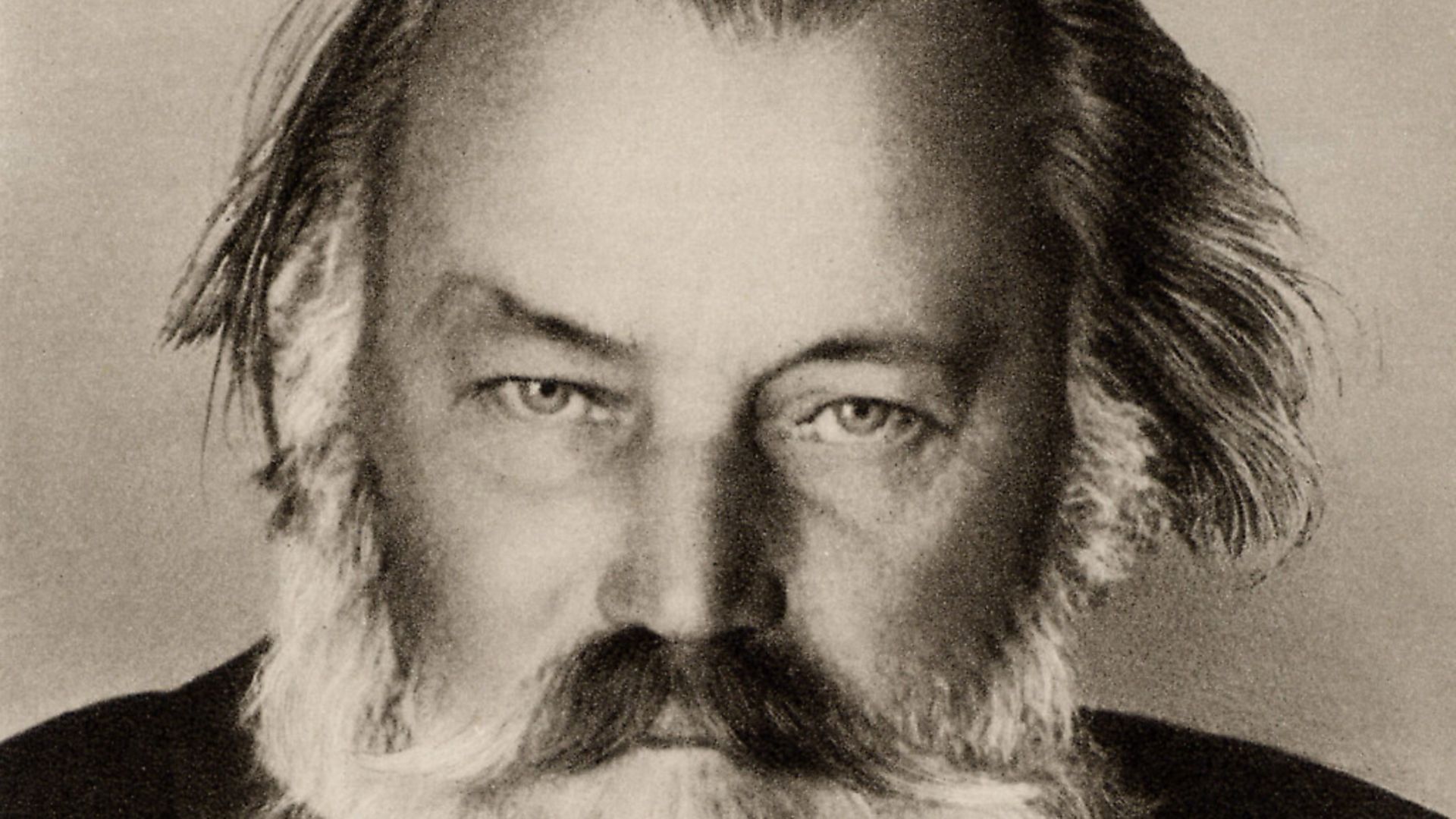

Johannes Brahms was a much more accomplished bilingual. We might suppose that, as a German, his native language was German. But he grew up in Hamburg speaking the local variant of the language known in German as Plattdeutsch or Niederdeutsch, and in English as Low German. Brahms came from a fairly well-to-do family and was also perfectly comfortable speaking German, which would have been the language he spoke in Vienna where he spent much of his life. But the depth of his feeling for the language of his native city can be gauged from a conversation he is reported to have had with the Low German poet Klaus Groth, who asked him why he did not set any verses in his native language to music, only poems in German. Brahms replied: ‘It doesn’t work. I just can’t. Low German is too close to me, it’s something more than just language to me. I have tried, but it doesn’t work.’ For Brahms, Plattdeutsch was ‘something that comes straight from the heart’.