What does it mean, ‘to be fair’? In this extract from his new book, BEN FENTON explains the concept of ‘fairness’ came to have such a central role in modern society, particularly in the English-speaking world.

In 1690, the English philosopher John Locke, a man whose work influenced Rousseau, Voltaire, Tom Paine and Kant, published Two Treatises on Government in which he wrote:

“The only way whereby anyone divests himself of his Natural Liberty, and puts on the bonds of Civil Society is by agreeing with other men to joyn and unite into a Community, for their comfortable, safe and peaceable living one amongst another.”

Locke was a 10-year-old child when the English Civil War broke out. His father, a lawyer and a Puritan, had served as a captain of cavalry on the Parliamentary side and was scarred by the experience. The young Locke was educated in the immediate aftermath of the most horrific collapse in the communitas regni – the “community of the realm” that England ever experienced and it shaped his view of how a social contract should be drawn up between governed and governors. He was drawn towards compromise rather than conflict. When William of Orange became King of England in 1689 in a bloodless coup and signed the Bill of Rights that shared power between Parliament and the Crown, Locke was the man to provide the philosophical bedrock on which the new polity would be built.

The process of coming together in a state of fairness in 1689 traded off absolute rights of monarchy against absolute liberties of subjects.

If you could put a date on the ‘birth’ of fairness, I think it would be this one. A people decided, for the first time, to negotiate a balance between cooperation – horizontally among each other – and competition – vertically between governed and government.

In reality, Locke’s Two Treatises and indeed the Bill of Rights merely set down guidelines for how a fair social consensus might arise, guidelines which subsequent generations refined, rejected and redrafted. But if you like the convenience of start points, this might work. Of course, setting a date for the birth of fairness is like setting a date for the beginning of logic or art.

The thought processes, the instinct, the visceral drive towards fairness were all there within us – it simply lacked a name. That post-Civil War period of history, certainly as far as the British were concerned, gave fairness breath and life.

Why is fairness important to us? It isn’t quite pain, but it’s more than emotion, isn’t it? The feeling that floods into your mind and body when you experience something that just isn’t fair.

You might be watching your child on a sports field and nobody will pass them the ball. You might be listening to a work colleague being heavily criticised for something that you know is not their fault. You might be queueing to leave the motorway and somebody drives right up to the front of the line of stationary cars and just muscles in.

If you are anything like me, any one of those experiences could make your blood boil. And when I say ‘anything like me’ what I mean is: if you are also a Homo sapiens.

Because the thing is this: all of those things I have just described excite a reaction in our brains. It is not a process we have learned, like changing gear, or frying an egg.

That feeling of unfairness is something else. It is innate and latent in all of us. Feeling that something is unfair requires that we have a well-developed concept of what is fair. (Whether fairness and unfairness are actually opposites is not a straightforward question, but for now, let’s just imagine that they are at the very least co-dependent.)

Both instincts are strong, irresistible in our minds because they are cogs in a machinery of thought and reaction which define our status, our personality, our safety, our place among our fellow human beings.

The most important thing we can know about ourselves is this: where do we stand in relation to other people? This is not a trivial question, particularly when applied to our positions in reference to people with whom we do not share a common bond of blood or love.

At the beginning of human time on Earth, that question – where do I stand in relation to others? – would define my chances of survival and of the survival of my genes. Nothing could be more important.

Could an individual live alone in a hostile environment? Possibly, but not for long and they would, of course, not be able to reproduce which, if anything, is a greater drive than survival.

The existence of a lone human would, both from their own point of view and an evolutionary one, be wasted. Could humans survive as a single-family unit? Yes, but the children’s opportunities for reproduction would be fatally limited. Could they survive as an extended family or small clan? Yes, more easily, but the limitations of interbreeding would put a cap on their chance of thriving as a group.

Wider interaction would be needed. Therefore, humans needed to have relationships outside their immediate family or clan groups to achieve more than basic survival and reproduction.

That meant cooperation and, in the case of the hunter-gatherers that we were until only 12,000 years ago, it meant cooperation with other groups of humans with whom we were otherwise in competition for food, water, firewood and shelter.

These two instincts – cooperation and competition – were the main drivers of our progress as a species.

To construct anything beyond basic societies, it follows, we needed to overcome natural instincts to compete with others in order to cooperate and, anthropologists believe, this is the reason Homo sapiens emerged triumphant over other species of homo: because of our ability to work together in larger groups, unlike other hominins.

By cooperating, we competed successfully against others with whom we could not cooperate.

Tens of thousands of years later, each of us still must evaluate constantly how we relate to others and make the same calculations of self-interest. Some of

us are preconditioned to be highly competitive and some to be highly cooperative; most of us are a bit of both.

Yet the evidence, in everything from parliament to a game of park football, suggests that we have developed a response to the complexities of contrasting interests that are pursued both by individuals and by small, related groups.

The response is such that we can successfully achieve a balance between competition and cooperation. In turn, that has allowed the construction of enormous structures of mutual benefit between strangers who will never meet or speak and who have wildly different desires and motivations.

Think of the NHS or the taxation system or elections; think of Manchester United or Black Lives Matter or the building society movement or Twitter; think of any corporation that shares its ownership with anyone who can afford to buy one unit of its equity. Think of the language of business: share; equity; credit; trust; bond.

Our understanding of trade in particular developed a language based on mutual relations and governed by a simple principle: fairness. Fair trade, fair exchange, fair prices: these are not modern concepts. They come from deep within us.

From the basic principles of trade, as prosperity born of commerce bought us the luxury of spare time, we developed more systems to enhance our enjoyment of life and leisure. Those systems were based on the same principle.

Think of an art gallery or museum or a public library, where collections of intellectual property are made available – in Britain, gloriously, for free apart from the payment of taxes – to people who could neither afford to buy them nor who would ever be guests of those who could.

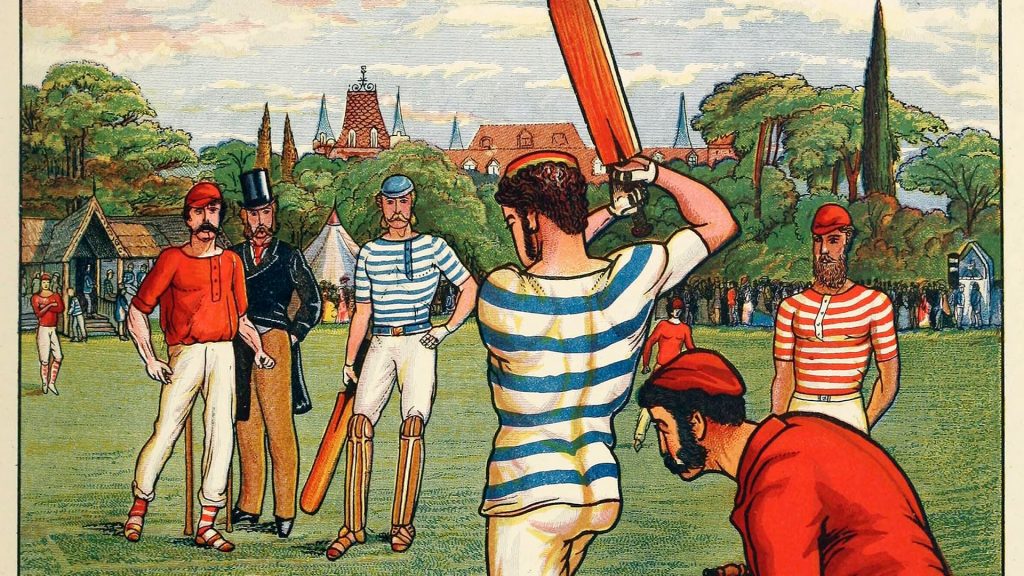

Think of a game of football or cricket in a park, where total strangers can join and participate because they know the rules and know what is and is not tolerated behaviour – beginning with the fundamental idea that the number of participants on each side must be balanced to make the competition mutually rewarding.

Think of government, where vast numbers of different opinions on a vast number of topics are resolved into a balance of views to produce laws which we are all (more or less) content to obey.

In every case, cooperation makes competition possible and competition makes cooperation necessary. What is the ingredient that allows this to happen? It is the common understanding of how we ‘play’ together.

In its basic state, playing together – one thinks of the enormous, unstructured games of ‘football’ in the Middle Ages where the entire male populations of rival villages

cooperated in order to compete – has a close approximation to war.

Yet we know that even under the application of chivalric rules – perhaps the first code of Fair Play – war leaves no winners. Thus, over time, we sought the thrill of

competition and the satisfaction of cooperation in a mutually ordered way. We introduced rules of how to play.

Our recent ancestors, the Victorians, applied the idea of fair regulation to play. Their own ancestors had used fairness to bring order (and therefore prosperity) to government after the horror of the English Civil War and then to bring order (and therefore prosperity) to business as the Industrial Revolution and international trade ignited commerce.

Applying regulation to play meant agreeing rules of conduct: one of the insuperable problems of playing football or cricket in the 18th and 19th centuries was that everyone followed different rules. So, the Georgians and Victorians did what they had been doing since the Enlightenment to everything that they considered inefficient: they regulated it from central principles.

They followed the same basic aims as in government and business: order from mutual agreement; trust between participants (enforced by the fear of anarchy or authority) and the sacrifice of any profound advantage that could mean that one side would never win (such as having many more participants or playing down a steep

slope while the other side always had to toil up it).

Then they wrote down the rules so that everyone knew how to construct that balance between cooperation and competition.

The underlying principle of all these things, the underlying principle of life in our society, is that we all conduct ourselves according to mutually agreed rules even if they don’t give us an advantage, because we know that others have to feel benefit if they are to participate.

If they won’t cooperate, we won’t have a game. That game could be football in the park; the game could also be called ‘Britain’, or ‘the USA’.

The diversity that most of us celebrate in the mix of minds and bodies that comprise our nations drives us to act and think in divergent ways. The mix has rapidly become more diverse since the end of the Second World War, more diverse at a pace that our processes of mutual agreement and consensus-creation have not been able to keep up with.

Directly as a result of this mismatch of change versus stability, the process of divergent thought and conduct, which deeply thrills many people just as profoundly discomfits others who have yet to be convinced that diversity is necessarily a good thing for them or for the world in which they live.

One thing I have learned from reading data about the way people trust each other in the spheres of politics, business and the media is that there is a simple way of expressing the contrast between those who welcome change without much thought for consequences and those who oppose change without much thought for potential.

It is this: do we want to be people who ask ‘can we?’; or people who ask ‘should we?’ Which is the dominant force in life?

By now you may be able to anticipate my own conclusion: we should be both, in balance. The function of fairness in a social contract is not just a top-to-bottom guarantee that the powerful will not exploit the powerless and the powerless will not seek to overthrow the powerful.

It is also a side-to-side agreement that we will take into account each other’s views and preferences, our various fears and desires, when setting our common course. (It is preferable to do this without a civil war.)

Fairness is a basis for consensus and it compels and permits us to cooperate and compete within the same set of agreed rules. Whether or not we have an interest in sport, the expression of fairness in the idea of Fair Play is something which we all have in common, regardless of culture, status, sex or age.

To Be Fair: The Ultimate Guide to Fairness in the 21st Century, by Ben Fenton, is published by Mensch and available through Bloomsbury Publishing

Ben Fenton was the chief media correspondent of the Financial Times and the senior reporter and Washington correspondent of The Daily Telegraph

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk