The grim politics of the Irish border are far from the bravado of Brexiteers says Stephen Travers, survivor of the Miami Showband massacre, one of the most notorious atrocities of the Troubles. Ahead of a new documentary on the subject, he spoke to TONY EVANS

Bombs, bullets and borders are never far from Stephen Travers’ mind. For the 68-year-old the word ‘backstop’ is not an arcane question to be debated or derided. The grim politics of the Irish border left Travers wounded and feigning death while his friends were murdered. The glib approach of some Westminster politicians to the impact of Brexit on Ireland and Northern Ireland appals him.

‘There’s so much bravado and gung-ho coming from Leavers,’ he said. ‘People like Jacob Rees-Mogg are saying there’s no problem with the border, let’s go back and monitor things as we did during the Troubles. They have not learnt the lessons of the past. They are playing fast and loose with people’s lives.’

Travers’ story, forgotten by so many, will be aired to a global audience on Netflix from March 22. ReMastered: The Miami Showband Massacre, details a dark episode in British and Irish history. It is given greater resonance by the political uncertainty generated by the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union.

‘Brexit is a disaster for Ireland,’ Travers said. ‘It’s a disaster for Britain. It’s exposed division. It’s an emotional movement rather than rational. Europe is a glue that brought us together in Ireland and gave us a common purpose. It’s dangerous to tear that apart.’

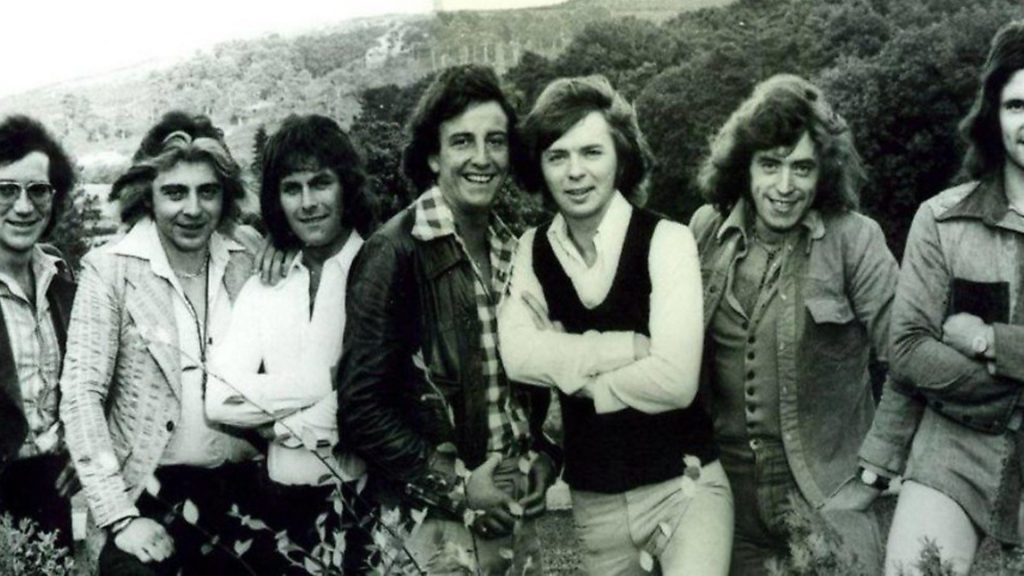

In 1975 Travers was the bassist in the Miami Showband, the most popular group in Ireland. They played six nights a week to crowds that could swell to 3,000. Performing a mixture of classic covers, hits of the day and original material, the Miami were regular commuters across the border, generally visiting Northern Ireland twice a week. In the early hours of July 31 the band were travelling south after a successful gig in Banbridge. Their Volkswagen minibus was stopped on a quiet country lane by what appeared to be an army checkpoint.

‘It wasn’t unusual,’ Travers said. ‘Most of the time the soldiers recognised the band and waved us on. This time they asked us to get out and line up facing away from the van. But we weren’t concerned.’

The patrol was comprised of soldiers from the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR), a locally recruited, largely part-time force that at one time was the biggest regiment in the British army. What the musicians did not know was they were also members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), one of the deadliest loyalist terror gangs.

Five members of the band shuffled into line beside the road: Travers; Fran O’Toole, the heart-throb singer; Tony Geraghty, a guitarist; Brian McCoy, a trumpeter; and Des McAlea, who played saxophone. Ray Millar, the drummer, was absent, having gone to visit his parents in Antrim. ‘We were a mixed lot,’ Travers said. ‘Catholic and Protestant, from north and south. We just wanted to play music.’

At first the interactions between the band and the troopers were jocular. ‘One said ‘I’d bet you’d rather be home in bed than standing on the road.’ Fran replied, ‘I’d bet you’d rather be in bed than crouching in a ditch.’ It was that kind of banter.’ The mood turned serious when another soldier arrived.

‘He was wearing a different type of uniform – it was lighter – and a fawn beret, light brown,’ Travers said. ‘He had a very professional demeanour and an English upper-class accent. He took charge immediately.’

The presence of the officer was reassuring. The UDR, which was disbanded in 1992, was an overwhelmingly Protestant force and had a reputation for handing out rough treatment to Catholics. As the soldiers searched the bus, Travers was concerned that they would damage his bass. When he heard the catch on a guitar case click, he moved to the back doors to try and ensure his instrument was not harmed. A soldier slapped the bassist’s outstretched hand with the barrel of a rifle and forced Travers back into line with a thump in the back with the butt of the weapon. ‘I wasn’t scared,’ Travers said. ‘I just thought he was a rough person.’

While the band reassured each other that things would be OK, two soldiers were planting a 10lb bomb under the driver’s seat. The device was poorly constructed. It exploded prematurely, blasting the two UVF men to smithereens.

The van disintegrated. ‘I tried to run but could not because I was blown into the air,’ Travers said. ‘The shooting started immediately. I don’t remember being shot but the bullet – what they call a dum-dum – entered my right hip, exploded in 16 pieces and continued into my left lung and left arm. They tell me I was shot while in the air but I don’t know. I began to fall down into the ditch, about a three-metre drop. It felt like it was in slow motion. Then I hit the ground really hard and two other people fell on top of me.’

The plan had been to plant the bomb in the van and allow its occupants to continue on their unsuspecting way. When the explosion occurred – the timer was set for 15 minutes later – it would appear that the Miami Showband were terrorists, transporting a bomb. The security forces in the north were frustrated that the border was so porous. The Irish government, it was felt, was not doing enough to stop Republican paramilitaries escaping south. If such well-known cross-border commuters as the band were engaged in terrorism, then Dublin would have to bow to pressure and increase checkpoints and patrols. In effect, it was a plot by terrorists to create a hard border.

‘It was a brilliant plan,’ Travers said. ‘If the IRA committed an atrocity, once they crossed the border they were safe. The British forces needed the Irish Government to have a much more stringent stop and search policy. Dublin was very reluctant to do this. There were people who criss-crossed the border two or three times a day, whether for cheaper groceries or cheaper petrol. They felt that if they disrupted this they wouldn’t get re-elected.

‘The British forces were using loyalist paramilitaries as proxy. They were controlling them.’

The conspiracy failed because it was badly executed. But beside the burning van, executions began.

McCoy tried to drag his injured bandmates to safety but the gunmen clambered down the three-metre drop in pursuit. The trumpeter was from a unionist background but that did not save him. ‘Brian was the son of a member of the Orange order, a Protestant lad trying to pull a Catholic from south Tipperary out of the way. He was murdered for his trouble. They shot him in the back of the head. He died beside me.’

O’Toole and Geraghty were next. ‘I can still hear the obscenities of the soldiers swearing and shouting and the cries of our lads asking not to be killed,’ Travers said. The lead singer was singled out for special treatment. ‘Fran was a good looking lad, a lovely fella. They shot him 20 times, seven bullets in the face. They did such a job that police didn’t know if he was a boy or a girl because he had long hair. Can you imagine the savagery?’

McAlea had been thrown into the ditch and lay unnoticed by the killers. Flames were sweeping down the hedges and the saxophone player thought he might burn to death. Meanwhile one of the soldiers stalked the field, kicking the bodies of the musicians and administering a coup de grace if there were any signs of life. Travers lay still, playing dead. Then the group of terrorists and their handler left. McAlea flagged down a car at the second attempt and was taken to the Royal Ulster Constabulary station in Newry to raise the alarm.

For many years Travers tried to put the incident from his mind. ‘I survived,’ he said. ‘The other lads died. I was OK.’ As part of the criminal injuries compensation process he was sent to be assessed by a psychiatrist. ‘I didn’t want to go. He would say ‘how are you?’ I’d say ‘I’m fine.’ He said: ‘You shouldn’t be.’ Eventually, he said ‘You might be the one in a million, the one in 10 million, who can handle something like this but I have to warn you that in six months, a year, five years, the wall might fall on you.’ That was the phrase he used.’

The bassist also shrugged off any thoughts of collusion between Crown forces and loyalist terror groups. ‘I thought the army and the police were good guys,’ he said. ‘I was brought up to respect law and order – I didn’t even question the fact that there was a British officer there and I brought it up to the lawyers when we had the preliminary trials. Will I tell them about this man with the English accent and the different uniform? And they said no, it didn’t matter. In hindsight, I should have done.’

Travers resumed his career as a musician and spent a number of years in London. He returned to Ireland in 1997 at a time when the mood was changing. Within a year the Good Friday Agreement brought peace to Northern Ireland. He began talking about his experiences and became increasingly vocal as an advocate for victims of terrorism. Speaking engagements took him across the world. One invitation from the Peace Centre in Warrington – a foundation set up in memory of Tim Parry and Johnathan Ball, the children killed in an IRA bombing in 1993 – had a huge effect on Travers.

‘This was not standing at a podium,’ he said. ‘You join a group and sit down and talk about your experiences.

‘They asked people to bring a memento of the incident that changed their life. I had a guitar string that Tony had left in my house a week before he was killed.

‘He changed a string, put the old one in the pouch and left it there. I kept it in the office all these years, just on the shelf. I took it to Warrington.

‘We were sitting around that evening, very relaxed. It was very casual. One man stood up and said he served in the British army in Aden and he talked about the terrible things he’d seen. He’d brought along a toy fire engine that a child would play with – he’d always wanted to be a fireman but he’d been abused as a child and got into alcohol and drugs as a survival mechanism and ended up in the army. He was so badly damaged. The more he spoke, the more I wanted to stand up and help him. I thought, ‘I want to say something really profound to help this man’.

‘It came to my turn. I stood up with confidence. I said ‘My name is Stephen Travers and I brought along this’. I put my hand in my pocket to take out the guitar string. Then the wall fell on me – instantly. It was one of the worst experiences of my life. No words would come. The tears were flowing. I couldn’t talk. And there’s this man I was pitying two minutes before, this poor soldier, and he’s got his arm around me.

‘People all around me were saying ‘This happens – don’t worry. It happens to everyone’ but I wasn’t in Warrington any more, I was in a burning field. The whole thing was happening again. I remembered so much more. It took me more than two years to get over that. I couldn’t do any of the things I’d become confident in doing.’ More than 35 years after the event, the trauma had caught up with him. But the trauma had not caught up with most of Northern Ireland.

Travers’ response was to set up the Truth and Reconciliation Platform (TaRP) in 2016. TaRP endeavours to address the legacy of the Troubles and promote healing within communities scarred by decades of violence.

‘Once you cross the border you feel the whole country is traumatised,’ he said. ‘We aim to show that no one has the monopoly on suffering. Legacy issues are not only about dealing with the past. It’s dealing with the future. Is this the kind of society we want to leave our children?’

The continued ignorance of British politicians astounds Travers. Karen Bradley’s insensitive performance in the Commons – where the secretary of state for Northern Ireland suggested deaths caused by security forces in the province were ‘not crimes’ – did not surprise him. ‘For decades, Northern Ireland was torn asunder by sectarianism, bigotry and violence,’ he said. ‘Today, its enduring and unrelenting misfortune is continued through the failure of British administrators to understand its people and their history.’ Brexit, sadly, proves that.

Tony Evans is a columnist for the Evening Standard and former football editor of the Times

ReMastered: The Miami Showband Massacre is released on Netflix on March 22