Manchester’s musical conveyer belt has been responsible for some outstanding acts over the years. SOPHIA DEBOICK tries to join the dots between them.

“My childhood is streets upon streets upon streets upon streets.” So Morrissey – once the master of ironic kitchen sink portraits of Mancunian life – opened his memoirs, evoking the endless terraces of 1960s Hulme, the heart of poverty-ridden post-industrial Manchester. A slow post-war decline was already being felt in that decade, but as the Beat Boom exploded, Britain’s second city was also fast becoming a musical powerhouse, exporting its sounds around the globe as it had once exported cotton.

In the 1960s Merseybeat was busy changing the world, but ‘Manchesterbeat’ aided and abetted the effort. A small local scene of coffee bars and nightclubs developed in the city centre, Top of the Pops was broadcast from studios in the Rusholme district for its first two years, and local bands started getting traction, even on the other side of the Atlantic. In the spring of 1965, a trio of Manchester bands topped the Billboard chart, sustaining the British Invasion and putting the city’s mark on pop history.

Freddie and the Dreamers, fronted by diminutive and hyperactive ex-milkman Freddie Garrity, were at No. 1 with their I’m Telling You Now in early April 1965, the bubblegum hit staying there for two weeks before they were knocked off by Wayne Fontana & the Mindbenders’ The Game of Love. That single was a far grittier affair, bearing the clear influence of the kind of American R&B and soul played at the Twisted Wheel club on Manchester’s Brazennose Street, and which was the cradle of Northern Soul.

Wayne Fontana was usurped from his place at the top of the US charts by Herman’s Hermits, who spent a fortnight at No.1 with the twee Mrs. Brown You’ve Got A Lovely Daughter (Peter Noone played up his Lancashire accent to its fullest effect on the record). The week of April 24, when the three bands occupied the top 3 positions on the Billboard Hot 100, was one of Manchester’s greatest ever musical moments.

The Hollies – formed from the nucleus of Graham Nash and Allan Clarke, who had met in Salford as schoolboys – never took the ultimate prize of US No 1 and arrived at the tail end of the British Invasion, but they had Top 10 hits in the US with He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother (1969), Long Cool Woman (In A Black Dress) (1972), and The Air That I Breathe (1974). But just two years after that last big hit, a new sound emerged which made it seem like something from the Stone Age.

The Sex Pistols’ June 4, 1976 gig at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, where a newly-electrified Bob Dylan had been denounced as “Judas” 10 years before, changed the path of Manchester’s – and by extension, Britain’s – music. Organised by Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks, who supported the Pistols when they returned to the venue six weeks later, the gig was attended by only about 40 people. But among them were the future luminaries of the Manchester music scene.

A 17-year-old Morrissey was there. Reviewing the gig for the NME, he denounced the Pistols’ “discordant music”, “barely audible audacious lyrics”, and clothes which “look as though they’ve been slept in”. Fledgling producer Martin Hannett and Peter Hook, a Salford Council clerk at the time, were also present. Hook went straight out the next day and bought a bass guitar at Mazel Radio on London Road, and soon formed Joy Division with Bernard Sumner and Ian Curtis, the latter a former employee of Rare Records on John Dalton Street turned job centre officer.

Curtis had attended the second Pistols Manchester gig, as did Mark E. Smith – who promptly formed The Fall – as well as Tony Wilson. Wilson was presenter of Granada Television’s music programme So It Goes, and he would invite the Pistols on to the show that August, giving them their first TV appearance.

When the Pistols returned to Manchester twice that December to play the newly opened Electric Circus in the run down Collyhurst area of the city, they cemented their energising effect on the Manchester scene. Records began pouring out of the city. In January 1977, Buzzcocks released their Martin Hannett-produced Spiral Scratch EP. Put out on their own label, it took punk’s DIY ethos to its logical conclusion. Hannett also produced Slaughter and the Dogs, punk poet John Cooper Clarke and Jilted John – whose eponymous single, with its mantra “Gordon is a moron”, was a No. 4 hit in September 1978 – for Rabid Records.

But when Howard Devoto released Shot By Both Sides with his new outfit, Magazine, in January 1978 it signalled the arrival of post-punk, and one label in particular would be vital to this new direction. Tony Wilson founded Factory Records in January 1979 and poached Hannett from Rabid. Informed by the ideas of the Situationists, Factory was artistically ambitious, and under its auspices the white heat of punk would be replaced by the icy alienation of post-punk.

Early Factory releases included the dreamy experimental works of The Durutti Column and the initially more aggressive sound of A Certain Ratio, but the first LP on the label would be Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, appearing in June 1979. Hannett’s sombre, effects-laden production and Ian Curtis’ monotone yet angst-ridden vocals seemed to portend of Manchester’s accelerated decline under Thatcher who had entered Downing Street just the month before the album’s release.

Curtis’ jagged on-stage performances – dancing awkwardly in a trance-like state – made him a unique presence on the live scene, and stark photography of the band by Anton Corbijn and local man Kevin Cummins, including famous images on Hulme’s Epping Walk Bridge and at T.J. Davidson’s Rehearsal Rooms on Little Peter Street, cemented their forbidding image. But Joy Division were a band whose longevity was in inverse proportion to their legacy, as Curtis’ suicide in May 1980 cut them short. Their single of the following month, Love Will Tear Us Apart, was propelled to No. 13.

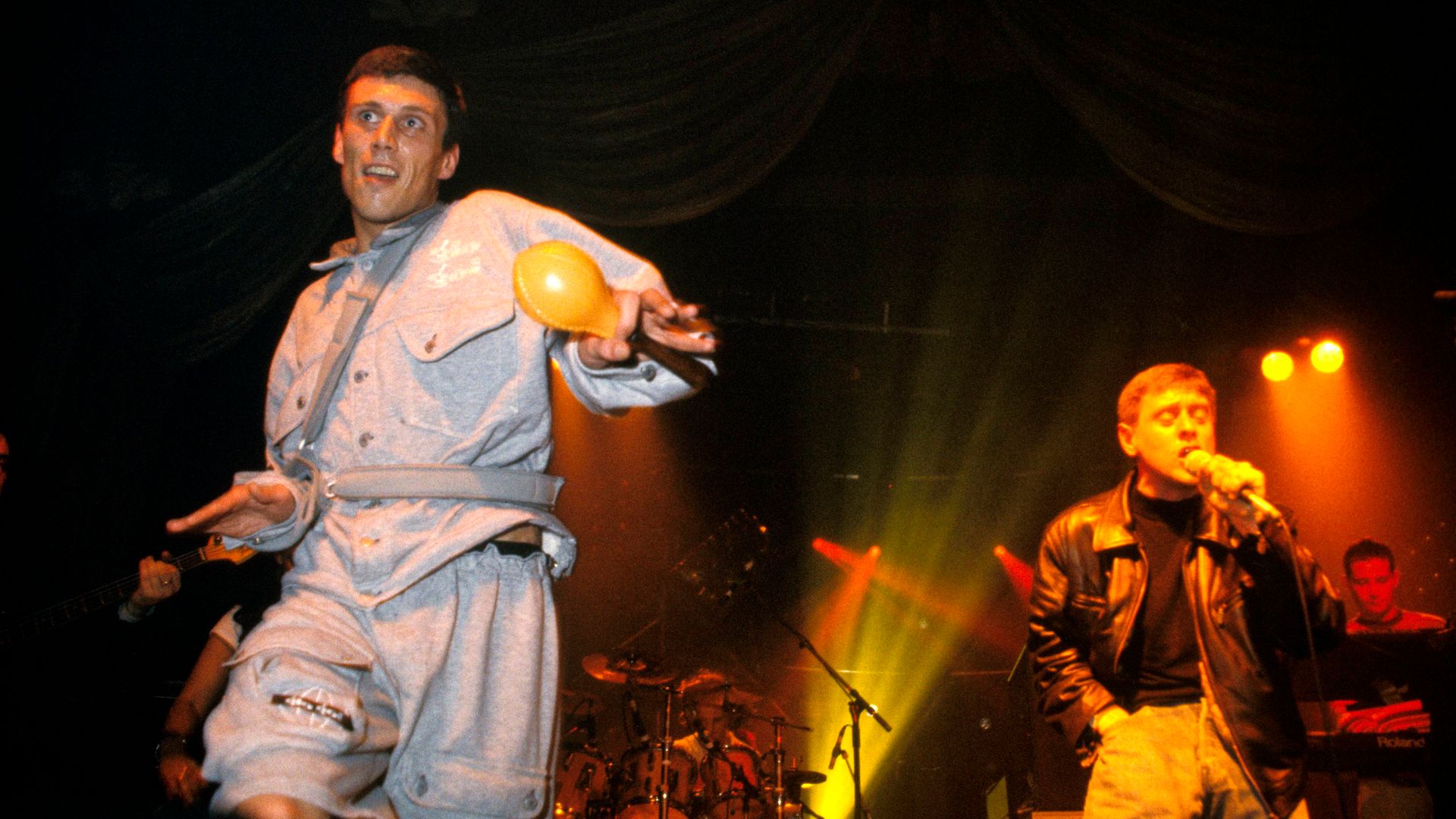

Joy Division had been all about desolation but as New Order the surviving members were central to a new, hedonistic era for Manchester around Factory Records’ Haçienda club, opened in a former warehouse by the Rochdale Canal in 1982. As dance music became the sound of the decade, New Order embraced it and their success – beginning in earnest with 1983’s genre-disrupting Blue Monday – largely bankrolled Factory’s operations. The Happy Mondays, signed by Factory in 1985, and even more representative of the Haçienda’s drug-fuelled hedonism and Manchester’s place in rave culture, added to the success.

While Mute’s Inspiral Carpets and Silvertone’s Stone Roses also contributed to bringing ‘baggy’ and the ‘Madchester’ scene to prominence with their Top 20 hits of 1990, it was Factory’s golden year. New Order had a No.1 single with Italia ’90 anthem World in Motion, and the Happy Mondays’ LP Pills ‘n’ Thrills and Bellyaches, and its singles Step On and Kinky Afro, all went Top 5. Factory moved out of the Didsbury flat it used as offices into expensively refitted headquarters on Princess Street. In a perhaps not unrelated event, the label went bankrupt two years later. But the breadth of Factory’s legacy – from Joy Division’s grave nihilism to the Happy Mondays’ hyperactive exuberance – lived on.

As the 1990s rolled on, Manchester music rarely displayed the kind of sheer fearlessness that Factory was home to. Oasis conquered the world but displayed an unreconstructed, more than faintly ridiculous masculinity, and their success was arguably a triumph of derivative mediocrity.

Latterly, Noel Gallagher’s self-exposure as an anti-masker, Ian Brown’s championing of a raft of conspiracy theories and Morrissey’s embrace of the far-right For Britain movement has damaged their stock as Mancunian heroes. But even when its creators reveal themselves to be mere fallible humans, the power of the music goes on.

MORRISSEY’S MANCHESTER MYTHOLOGY

Morrissey explicitly referenced his home city on The Smiths’ 1984 eponymous debut, with its chronicle of the Moors Murders, Suffer Little Children (“Oh Manchester, so much to answer for”), and Miserable Lie, referencing a southern suburb (“What do we get for our trouble and pain/ Just a rented room in Whalley Range?”). A fair at Rusholme’s Platt Fields Park was the setting for Rusholme Ruffians (1985), while The Queen is Dead (1986) included Cemetery Gates (1986), set in Chorlton’s Southern Cemetery, and Vicar in a Tutu, which namechecked the city’s Holy Name church.