RICHARD HOLLEDGE on a series of exhibitions spanning Normandy highlighting the considerable role the region played in the influence of impressionism.

Nymphéas avec rameaux de saule, 1916-1919

Huile sur toile, 160 x 180 cm

Paris, lycée Claude Monet – Credit: Archant

Television gardener Alan Titchmarsh was at the forefront of the campaign to open garden centres during the lockdown. He argued they needed protection from the financial stress they faced as the potatoes and peonies, chrysanthemums and cabbages wilted away unsold but more, that gardens were a ‘vital source of solace and nutrition’.

The artist Claude Monet would understand that cry – a cri de fleur perhaps. From 1883 until his death in 1926 he dedicated much of his time and most of his passion creating his garden at Giverny, on the banks of the River Seine in Normandy. He declared it ‘my most beautiful masterpiece’.

The garden reopened to the public with the easing of le confinement on June 8 as part of an ambitious series of exhibitions entitled Normandie Impressionniste.

They had been scheduled to launch in April but now will be shown in galleries across the region in a series of staggered openings which will include 20 exhibitions on the Impressionists, 30 contemporary art shows as well as dance, digital art and street art.

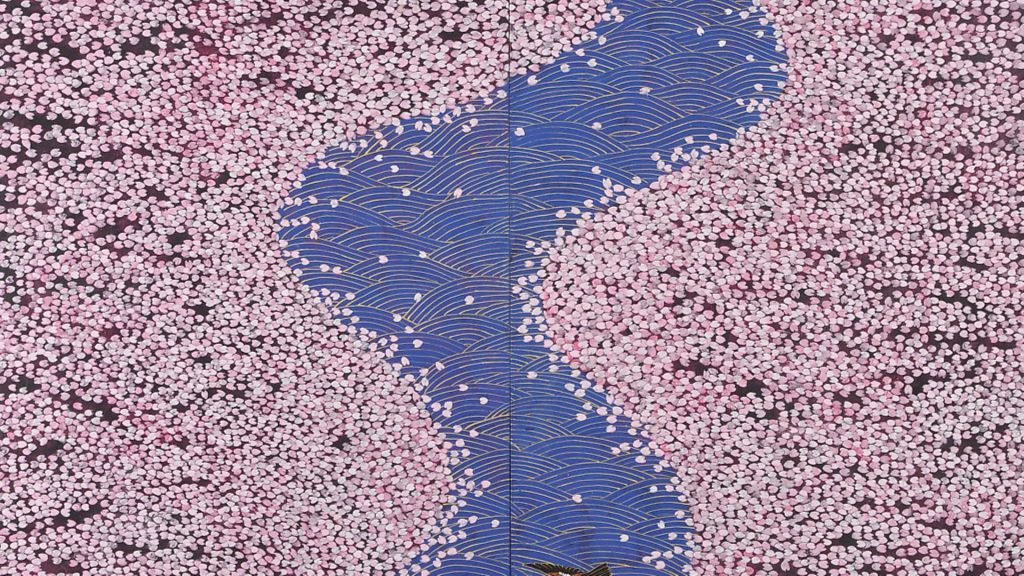

Giverny, l��tang de Monet, couleurs de printemps, 2015

Nihonga, 179,9 x 170 cm (diptyque)

Giverny, mus�e des impressionnismes, MDIG 2018.1.1

� Hiramatsu�Reiji

� Giverny, mus�e des impressionnismes – Credit: Archant

The enterprise is more timely than the organisers could have imagined when they were planning it pre-Covid.

Fundamental to the Impressionist movement was painting outdoors, en plain air. Sitting in front of an easel, come rain or shine, helped give their work a naturalism which in turn reflected a sense of freedom and well being.

One cannot push the parallel too closely with the darkness of our 21st century plague but the idea of breaking free from Paris with its endemic sickness, its grime and noise, in favour of a peaceful countryside or an invigorating sea shore is not that far from the eagerness of ardent sun seekers escaping the lockdown to travel from cities to the sybaritic joys of Southend beach or piling into urban parks for a breath of fresh air and sun on the face.

The Impressionists were drawn by the languorous landscapes along the banks of the Seine, the storm-tossed clouds over the Channel and turbulent seas crashing against the daunting cliffs of Étretat.

Les Promeneurs. �tude pour � Le D�jeuner sur lherbe �, 1865

Washington, National Gallery of Art, Ailsa

� Washington, National Gallery of Art – Credit: Archant

They delighted in observing the promenade of the fashionable along the soothing beaches of Trouville and were intrigued by the fishermen and their families who looked on with a mix of bemusement, envy and, perhaps contempt, at the ‘senseless luxury’, as one commentator put it, displayed by their visitors.

The appeal of resorts such as Trouville – unlike Southend – was summed up in a guide to France in 1856 which enthused that the town ‘offers that deep silence that encourages the spirit to contemplation, that sole peace that acts on the heart and brings serenity to the soul’. The guide also warns that the ‘fury of construction’ was a threat to that harmony. Again, without pushing the analogy too far, there have been many who in the past few months have much preferred a life without the bang and clatter of engineering works and building sites.

All this – the serenity and the senselessness – is set against the backdrop of clouds, billowing white or darkly storm-laden, the faint smudge of sun and always, the sea, lapping gently or charging wildly to the shore in a fury of foam.

Few caught the relentless power of the sea more eloquently than Gustave Courbet in his series, The Waves in which there are no humans or boats in the frame to get a sense of scale.

‘The sea! The sea! with its charms saddens me!’ wrote the artist, who worked so close to the shore that the waves crashed against his studio window. ‘She makes me in her joy, the effect of the laughing tiger; in her sadness, she reminds me of the crocodile’s tears, and in her fury, the caged monster who cannot swallow me.’

And the painter Paul Cézanne enthused, after seeing one of Courbet’s works for the first time: ‘It is like a blow to the chest, we step back, the whole room smells of sea spray.’

One might assume that the pretensions of class and society would be ignored in the face of something as potent as the roaring ocean and that the artists would be indifferent to the spectacle of Parisians on holiday but far from it.

Eugène Boudin won acclaim for a series on Trouville beach with its cavalcades of crinoline, umbrellas wielded against rain or sun, top hats, and daring types who ventured out of the bathing huts to dip a tentative toe in the foam.

In Lady in White on the Beach at Trouville, the lady in question is wearing a turned up skirt, revealing a red petticoat which allows more freedom of movement – the kind of liberation that would be frowned on in the formal strictures of Paris.

The hints and hopes of a flirtation are never far away. After all, Venus was born from the waves.

Claude Monet, hints at the ‘fury of construction’ by including the grand houses and hotels that were springing up along the coast in his beach scenes, though The Beach at Trouville, shows two women, the one on the left probably his wife Camille, and the other possibly the wife of Boudin in what is an intimate portrait of the simple pleasure of a day at the seaside.

As if to validate the spirit of plein air painting grains of sand are present in the paint at the bottom right, confirming that it must have been painted on the beach.

But it was by no means only the elegant crowd with their ‘absurdities and vices’, as an observer damned them, that the artists portrayed, but the people who actually lived and worked there.

Some of the artists considered them as a ‘race apart’ as the novelist Gustave Flaubert described them when he wrote: ‘Nothing could be more barbarous than the women who rolled up their sleeves and helped out with the harvesting mussels, shellfish, shrimps as well as doing the house work and tending flocks of sheep on the cliff tops.’

The sophisticated Parisians were puzzled that the homes of the locals faced inland and not out to the horizon, failing to understand that the sea was not only where they made their living but was also a place of danger.

Monet painted the fishing boats pulled up on the beach at Étretat, John Singer Sargent the oysters gatherers in Cancale and Boudin men working on the beach at Deauville with their horses and cart, tiny figures on an deserted landscape and under a vaulting cloudy sky. Édouard Manet’s marvellously evocative Claire de Lune captures the tension of the huddle of women as they wait for their men to return from their fishing expedition, the sepulchral darkness of the quayside lit only by the moon.

In an exhibition at the Fécamp Museum devoted mostly to the lesser known Eugène Lepoittevin, we see the sheer joie de vivre of ordinary families in Bathing at Étretat with its diving lads and girls floating in the sea in voluminous costumes while his Unloading the Fish at Étretat shows us a hard working family – that ‘race apart’ – doing what they have done for years until the holiday makers – and the artists – came on the scene.

There is none of this activity – whether by barbarous locals or soignée Parisiennes – in the calming enclave of Monet’s masterpiece, his garden.

Again, there is an aside to made about our current predicament – perhaps a more pertinent one than the great outdoors as a mere escape.

Alan Titchmarsh also quoted scientific papers claiming that gardens have a therapeutic effect and the case of the explorer, Robin Hanbury-Tenison is a good example.

The 84-year-old caught the virus on a ski trip just as the lockdown was being mooted and was on a ventilator for five weeks. A turning point for him came when he was wheeled out of the ward and into a ‘secret garden’ in the hospital. Not much of a garden, apparently, just a raised flower bed with some pots but this limited exposure to the natural environment helped his recovery.

One of the hospital nurses explained: ‘Intensive care is a very hard place to be. You don’t have much control, you’re in an unfamiliar environment and drugs can affect your level of consciousness. The garden is part of the humanisation process. We take patients outside, even if they are ventilated, so they can feel fresh air. There’s a power in the sunlight and fresh air and rain.’

Monet would no doubt understand that. ‘I am following Nature without being able to grasp her,’ he wrote. ‘I perhaps owe having become a painter to flowers.’

The garden is a diverting combination of iron arches on which climbing roses and wisteria flourish and alleys leading through flower beds in which poppies and daisies mingle with the rare varieties he spent much of his time seeking out.

Monet himself declared: ‘Colour is my daylong obsession, joy, and torment’ and he married flowers to each other according to their colours and left them to grow freely with the result that the first visitors to Giverny since the virus struck would have been greeted by an extravagance of irises, poppies, roses and hollyhocks.

And of course, the lily ponds. He had the first pond dug in 1893, much to the perturbation of his neighbours who feared his strange plants would poison the water and today it is a wonder of asymmetric corners and curves, influenced by the Japanese gardens that Monet knew from the prints he collected avidly.

He would get up early most mornings to catch the dawn light and every fleeting change in colour, shade and shape reflected in the lily ponds by the sky.

He said: ‘The richness I achieve comes from nature, the source of my inspiration.’

Normandie Impressioniste has been organised across many venues, including the Giverny Museum, the Caen Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum of Modern Art in Le Havre (MuMa), Cherbourg’s Thomas Henry Museum and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen. Opening dates vary. For more information, visit normandie-impressionniste.fr/