Thirty years after his death, a new biography of Steve Marriott, of the Small Faces, paints a bleak picture of rock excess.

The 30th anniversary of Steve Marriott’s death at the age of 44 – he died in a house fire on April 21 1991 caused by his falling asleep with a lit cigarette – finds the late rocker honoured far more widely than at the time of his passing.

Since his death, the likes of Paul Weller, Noel Gallagher, the Black Crowes, Ocean Colour Scene, Blur and others have all listed Marriott as a major influence. The jukebox musical All or Nothing (narrated by Marriott’s sodden ghost) has toured widely, tribute bands cover his songs, documentaries abound and, to vintage clothing aficionados, he’s the mod magus, one of British pop’s sharpest dressers. Joining this list is now All or Nothing: The Authorised Story of Steve Marriott by Simon Spence.

Spence’s effort is not the first biography of Marriott but will likely be seen as definitive: All or Nothing is an oral history employing interviews with family members, band mates, friends, managers, producers, record label executives and fellow musicians.

Marriott’s voice is there throughout, quotes from interviews he gave peppering the text. Spence’s authorial voice rarely intrudes, he only writes brief introductions (or outlines) so as to background time/place/individuals.

Beyond that its the voice of Marriott and those who knew and loved/loathed (sometimes both) him which detail his rise from Manor Park council estate to the most exciting voice in 1960s British rock (which is fascinating) and then the subsequent squandering of his sizeable talent and the long, slow, seedy decline (which is depressing).

By the time I reached the book’s finale at Marriott’s cottage in Arkesden, Essex, where the musician, comatose on valium, alcohol and cocaine (so unable to escape the flames), expires I also felt as if something in me had died: Marriott’s band the Small Faces were, arguably, the most exciting rock act of the mid-1960s, their music fizzing with a sense of wild, lucid possibilities – young London never before or after sounded quite so exalted – but I doubt I will now enjoy them quite as much as I previously did. For All or Nothing serves as a grim moratorium on British rock and toxic male behaviour.

Stephen Peter Marriott could well be described as an ‘urchin’ – a small boy and man (standing just over five foot) who grew up in a bombed out East End, his father playing piano in pubs and selling jellied eels: how much more Cockney could you get?

A hyperactive child, Marriott formed bands and won talent contests at a holiday camp in Clacton-on-Sea; his parents thus pushed him towards the stage: aged 13 (in 1960) he won an audition to be one of several Artful Dodgers in the West End production of Lionel Bart’s hugely successful musical, Oliver!.

Perhaps inevitably, Marriott developed his first addiction – to applause – here and for the rest of his life he would love striding the stage and working audiences. Enrolled at Italia Conti Academy – his fees deducted from the acting work the school found for him – Marriott looked to be shaping up as a young thespian but it was singing rather than acting that determined what he wanted to do and, in 1963, he released his first record. It flopped.

Unperturbed, Marriott formed The Moments and they began working London’s pub and club circuit. Tiny but possessing a powerhouse voice and great confidence, Marriott impressed many who heard him perform.

Encountering Ronnie Lane, another music obsessed teenager, in a Manor Park shop, propelled Marriott forward. As with Paul McCartney and John Lennon, Lane would play bass, co-write songs and act as a calm foil to the effervescent Marriott.

In 1965 the 17-year olds formed a band a female friend would christen the “Small Faces” –small, since none were over 5ft 6 tall, and faces in mod culture being an accolade bestowed upon respected mods.

Within a matter of weeks the Small Faces were making an impression on the circuit and would be signed to a management contract by Don Arden. The late Arden (born Harry Levy, 1926 – 2007) had started out working Manchester’s Yiddish circuit before taking on tour American rock’n’roll musicians.

Realising British beat bands were where the money was, Arden set up in London and became notorious for his strongarm tactics. Both ruthless and generous, he put the Small Faces on a weekly wage of £50, rented a West London house for them to live in and set up unlimited accounts for the band at Carnaby Street clothes shops.

The Cockney youths hungrily embraced the “good life”, oblivious to the fact that all their frantic spending would be charged against their earnings. Arden quickly ensured the band were earning – he negotiated a deal with Decca, spent thousands of pounds massaging their debut single Whatcha Gonna Do About It into the UK charts and, by 1966, had ensured they were one of the biggest bands in Britain.

It’s the period covering 1964 to 1966 that makes for the most engaging reading in Spence’s book. Here the London music scene is small, provincial even, with many now famous names bumping up against one another – Marriott and David Bowie had considered forming a duo called David & Goliath; Elkie Brooks directed Arden towards the band, impressed as she was by Marriott’s voice.

Spence has either interviewed – or made use of interviews – with all of the aforementioned, Arden’s brutal yet droll denunciations of his former charges lending the book a humour otherwise absent.

How four teenagers, all possessed of little more than rudimentary musical skills and without even a long gestation period of heavy gigging, came together to create such fresh, dynamic rock sound is never discussed here – this is a biography focusing on Marriott’s character rather than his artistry.

That the UK – whose best effort at rock in the 1950s was Cliff Richard’s Move It – had, by the mid-1960s, become an international powerhouse in popular music, remains pleasantly baffling. And Marriott might just have been the most engaging, inventive and exciting rock singer this ferment produced.

As well as a gifted songwriter: he and Lane wrote Tin Soldier, All or Nothing, Itchycoo Park, Lazy Sunday, Here Comes the Nice and a host of other standout songs. Yet it was all over by New Year’s Eve 1968 when Marriott stormed off stage at Alexandra Palace: the dynamic that fired up the Small Faces also splintered it.

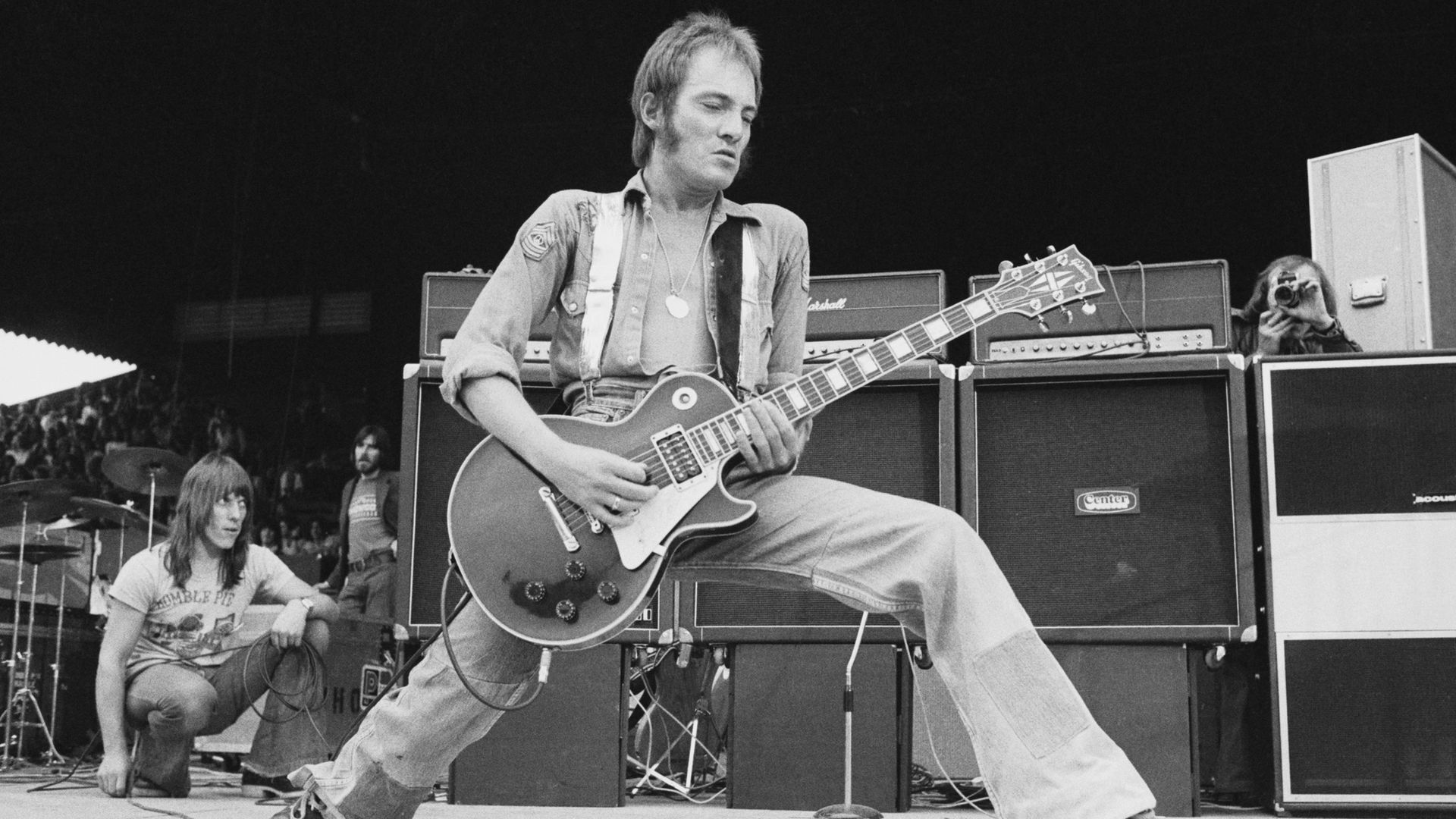

While the Small Faces had never experienced any lasting success in the USA, Marriott’s next band, Humble Pie would fill stadiums there across the first half of the 1970s, their music being no frills heavy rock.

Once more Marriott made and lost a fortune – this time his US management fleeced the band – and Spence’s detailing of the singer’s slide into cocaine psychosis and alcoholism is grim reading. Marriott appears to have been a supreme narcissist, incapable of comprehending why he alienated everyone he had any kind of relationship with (work or personal). “Talented as Steve was, he was just a bad guy,” says one interviewee. And that’s putting things politely.

The era of British rock bands dominating the charts is long gone. As is an unspoken code which allowed famous/wealthy people to behave extremely badly while rarely being reprimanded.

That Steve Marriott – who, from 1965 to 1968, embodied the excitement and possibilities inherent in British rock music – had, by the early-1970s, come to represent rock’s worst qualities, is worth pondering on.

From urchin to boor, artful dodger to asshole, Marriott’s decline across the 1970s/80s demonstrates how wit and talent can quickly shrivel, leaving a faded star with nothing to offer but a loud voice and ugly personality. All or Nothing serves both as a biography of a man and the spoilt British boomer generation who enjoyed plenty yet believed it was their right to squander far more.

All or Nothing: The Authorised Story of Steve Marriott, by Simon Spence, is published by Omnibus.