The Benin Bronzes have a special status in the debate over cultural artefacts taken during the colonial era. Author Barnaby Phillips explains why, and why the British Museum’s approach to the debate is unsustainable

At the end of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee summer, in September 1897, the British Museum hosted an unusual exhibition. It was something of a rushed affair, as the objects on display – hundreds of brass castings and sculptures – had only arrived in London a few months earlier.

Journalists did not know what to make of them. “Surprised”, “remarkable”, “baffled”; these words recur throughout their reviews. The objects came from the West African kingdom of Benin (located in modern day southern Nigeria, not the neighbouring country of Benin) which had been conquered by the British in February of that year.

Benin, according to British newspapers, was a place of barbarism, its streets littered with the victims of human sacrifice. And yet now, curators and art critics agreed, the finest of Benin’s sculptures were as sophisticated and beautiful as those from ancient Greece or Renaissance Italy.

There were further grounds for confusion. Africa, according to late Victorian consensus, was a place without history. And yet many of the castings from Benin, detailed depictions of Portuguese soldiers in armour from the 15th and 16th centuries, most likely dated from that time.

In fact, the Benin kingdom and its people – known as the Edo – had enjoyed a harmonious relationship with European traders and explorers for hundreds of years. The Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British had all been welcomed at the court of the king, the Oba, where they had traded guns, brass bracelets and cowrie shells for slaves, ivory and pepper.

Benin City was the capital of this kingdom, its streets and palaces compared favourably by European visitors to those of Lisbon and Amsterdam. By the 19th century Britain was the pre-eminent European power on the West African coast, and its relationship with Benin began to sour.

Glasgow and Liverpool traders were hungry for palm-oil and rubber, and the Oba was an obstacle to commerce. Some colonial officials argued for an invasion, and when, in January 1897, several British officials and traders were killed en route to Benin, the government in London agreed that the Oba should go.

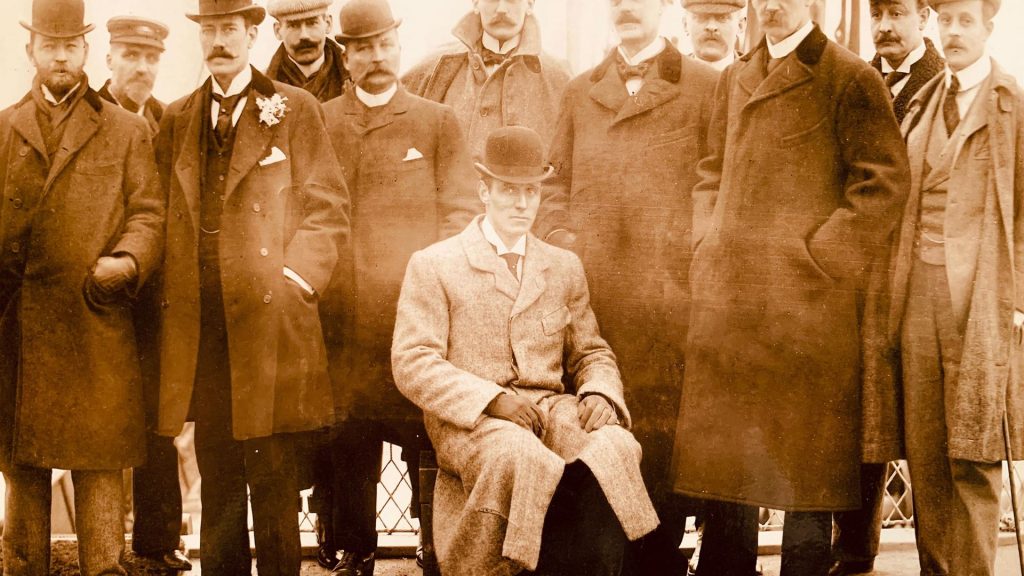

Admiral Harry Rawson’s ‘Punitive Expedition’, some 1,200 soldiers and sailors, despatched from Britain, Cape Town and Malta, with Maxim guns and rockets, mowed down the Oba’s soldiers armed with muskets and captured Benin City. The Oba was sent into exile, and never saw his kingdom again.

It was a classic small war of imperial conquest, one of Kipling’s “savage wars of peace”, but its distinctive significance to us today derives from what happened after the British had seized the Oba’s palace.

That was when Rawson’s men stumbled across the magnificent brass and bronze sculptures and castings, as well as ivory carvings which came to be known collectively as ‘the Benin Bronzes’. It was, said one officer, a ‘regular harvest of loot’, laid out in the courtyard for the British to take their pick, and carried back to the waiting ships by heavily-laden porters and donkeys.

Today, the Benin Bronzes are dispersed around the museums and private collections of Europe and the United States. That process of dispersal began almost immediately; the first auction took place in May 1897, when J. C Stevens’ auction house in Covent Garden advertised in the Times the sale of “Several Carved Tusks and other trophies from Benin city collected by naval officers in the recent expedition”.

There were many more auctions in subsequent years, as dealers, collectors and curators began to appreciate the significance of the Benin Bronzes, and officers saw the opportunity to cash in on their loot.

During this process their very meaning underwent a transformation. The Benin Bronzes had been made for religious and spiritual purposes, but also as mnemonic devices, recording the history and beliefs of the Edo people. But in Europe they were admired for their aesthetic qualities.

They had become pieces of art. German museums reacted with particular alacrity; the Berlin curator Felix von Luschan rushed to London in the summer of 1897 to make his first purchases.

Uniquely, Luschan recognised the Benin Bronzes not only as artistic masterpieces, but also as objects whose existence was a rebuke to the prevailing values of the time. The Bronzes, Luschan wrote, could help Europeans understand “that the culture of the so called ‘savages’ is not inferior to our own, only different”.

Some 120 years later, museums from Los Angeles to Leipzig are struggling to justify the morality of their collections of Benin Bronzes. In Europe the Black Lives Matter movement has accelerated an already critical interpretation of imperial history, and the Bronzes have become emblematic of the extremely charged debate around the future of colonial-looted art in western museums.

They’ve acquired a special status in this debate, for perhaps two reasons. The first is that they are magnificent, amongst Africa’s greatest treasures, and there are so many of them, (scholars still disagree on just how many thousands the British took in 1897). The second is the manner and timing of their theft.

The looting of Benin City was not a uniquely egregious act of cultural vandalism – from Maqdala to Mandalay, British 19th century military expeditions plundered treasures – but it happened towards the very end of the period of imperial expansion, and is extremely well documented in photographs, letters and journals.

Events are moving fast. In 2017 the French president Emmanuel Macron made an extraordinary speech on a visit to West Africa, saying that within five years, he wanted to see “conditions are met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa”.

The report he subsequently commissioned, which came out in 2018, was both a searing indictment of the history of Europe’s museums – “born from an era of violence” – and a radical blueprint for change. Several British museums now say they’re prepared to return their Bronzes.

These included the Horniman Museum in London, and the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, both of which have significant collections. The real bombshell came from Germany in April, with the collective decision by its government and museums to begin returning a “substantial” number of Benin Bronzes to Nigeria, starting in 2022. Germany’s culture minister, Monika Grütters, said “dealing with the Benin Bronzes is a touchstone”, of her country’s “moral responsibility”.

All of which raises the question, what about the British Museum, which hosted that first exhibition back in 1897? It has the largest collection of Benin Bronzes of any museum, almost 1,000, although it only displays some 100.

These include some of the most iconic pieces of all, including the Queen Idia ivory mask, believed to date from the 16th century, and to many Nigerians a symbol of both indigenous cultural achievement but also colonial oppression.

In truth, the British Museum is in an invidious position, prevented by law from permanently returning its Benin Bronzes, even if its trustees or director, Dr Hartwig Fischer, should want to do so.

Boris Johnson’s government has made its position clear; the culture secretary Oliver Dowden has written to national museums, telling them not to remove objects with “difficult and contentious” histories.

His letter came with a thinly veiled threat – that government funding could not be taken for granted – which carried significant weight in the midst of the pandemic when other revenue sources have collapsed. But there is also frustration within the British Museum; a feeling that its current leadership is not even trying to engage with the government on the future of the Benin Bronzes and other contested items, but would rather put out bland press statements and hope the problem simply went away.

Already, it is possible to see the outline of a looming PR disaster, whereby many leading European museums do return their Benin Bronzes, but the British Museum is only able to offer some on loan.

In Nigeria itself, there are three bodies with vested interests in the future of the Benin Bronzes: the federal government, the Oba’s palace (the dynasty was restored in 1914) and the Edo state government. Sadly, the discussion over to whom and how the Bronzes should be returned is already provoking rancour. “It’s about money and politics, not culture and heritage,” says one Western curator involved in the negotiations.

Awkwardly for the federal government, its underfunded museums already have a sizeable collection of Benin Bronzes – the colonial administration bought dozens of superb specimens in London auctions in the 1940s and 1950s – but have done a poor job at displaying them, and, in some notorious cases, failed to prevent their theft back to Europe and the United States. Meanwhile, there are simmering rivalries and jealousies between the Edo state governor, Godwin Obaseki and the current Oba, Ewuare II, who, as the great-great grandson of the Oba whose palace was ransacked in 1897, argues he is the ‘legitimate custodian’ of everything stolen that year.

In theory, the three Nigerian institutions are united in the idea of building a proposed new museum in Benin City. Governor Obaseki’s vision is ambitious; a world-class museum, designed by the celebrated architect Sir David Adjaye, at an estimated cost of $100-150 million. “We can make this win-win,” says governor Obaseki, pointing out that even if some Benin Bronzes remained in Europe and the United States, Benin’s new museum could still have a large collection. Nigeria’s recent history is full of squandered opportunities, and much could go wrong. But, for the first time since 1897, it is the Edo themselves who will play a crucial role in determining what happens next to the Benin Bronzes.

Barnaby Phillips is the author of Loot: Britain and the Benin Bronzes, published by Oneworld

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk