A new exhibition of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood serves as a useful opportunity to focus on its female associates, be they muses, mistresses or much more

When Stephanie Marrian became the first Page Three girl in the Sun newspaper in 1970 it is possible she was channelling the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Or maybe not. But she was undoubtedly, to use the journalistic parlance of the day, a ‘stunner’ a word which today has become so cheap and sexist that no man, let alone a tabloid journalist could possibly use. Not even with a neon arrow semaphoring ‘irony’.

But for the Pre-Raphaelites in the mid-19th century, a stunner was not merely an object of lust, though that played a considerable part, but a paragon of female beauty to be worshipped in drawings and paintings.

In the words of Georgiana Burne-Jones, artist, occasional stunner and wife of Pre-Raphaelite stalwart Edward, their work was “in a way sacred to them” and she recalled when she first met the group: “I felt in the presence of a new religion. Their love of beauty did not seem to me unbalanced, but as if it included the whole world.”

An exhibition at the Ashmolean, Oxford, Pre-Raphaelites: drawings and water colours (until June 20 ) illuminates their style and passion with works which are usually tucked away in a museum print room because they are too fragile to be left open to public gaze.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, or PRB, as they liked to call themselves, spurned the classical, often mannered, work of the artists who came after Raphael, the supreme High Renaissance painter, who died in 1520. They much preferred the rich colours and complex compositions, not to mention the moral purpose, of Italian Quattrocento masters such as Michelangelo, Botticelli, da Vinci et al.

The small group who got together in 1848 in London, and later Oxford, included John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Frederic Stephens and subsequently Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris.

They rebelled against what they considered to be the strait-laced teaching of the Royal Academy and were encouraged by John Ruskin, the arbiter of Victorian taste and culture, who advised them to “go to nature… rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing”.

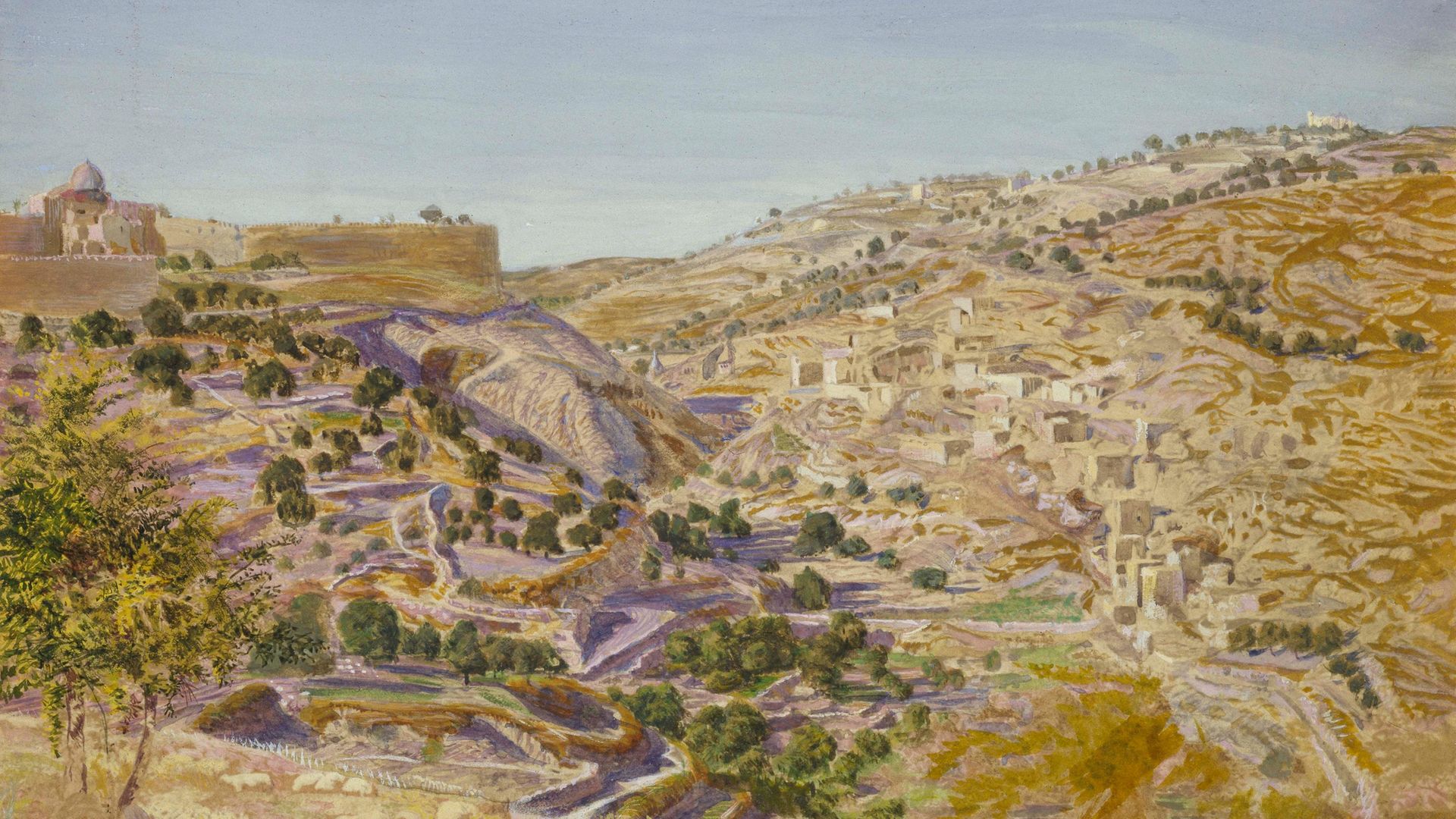

They painted idyllic landscapes in the hills and dales of the United Kingdom and ventured to foreign lands such as Jerusalem and Switzerland, but what attracted them most were literary themes and poetry, the mythical subjects taken from Arthurian legend, the Bible and literature.

Art, they argued, should be naturalistic and artists should study, not from antique models and casts but directly from nature and from the human figure.

One often gets a greater insight into this radical approach from the preliminary sketches than the burnished luxuriance of the finished article. The pen and sepia ink drawing The Apple Gatherers by Millais, with its group of girls relaxing in the countryside, has a natural charm of its own and illustrates the artist’s original thinking – his practise run, as it were – bursts into technicolour brilliance with Spring (Apple Blossoms), 1856-7.

There is a surprising power in the pen and ink illustrations Millais drew for an edition of Alfred Tennyson’s poetry, The Moxon Tennyson (1855-7), perhaps none more poignant than St Agnes Eve, which depicts the martyred St Agnes, patron saint of chastity, standing by an open window, a taper in her hand breathing into the cold night air. “My breath to heaven like vapour goes.”

Again, using only pen and brown ink Rossetti brings a terrible intensity to The Death of Lady Macbeth (c.1875-6) as she cries, “Out damn spot! Out I say…”

The creative process is exemplified in the figure of Christ sketched out on the back of an envelope in Studies for the Light of the World by William Holman Hunt (1851) when it is compared with the glowing passion of the finished oil which Ruskin declared to be “one of the very noblest works of sacred art this century or of any age”.

Proof of the whirling imagination of Holman-Hunt – and typical of the PRB’s quest for ideas – is a rough pencil drawing on the same envelope which appears upside down for an idea he had about the Wars of the Roses in which a Yorkist soldier tries to persuade a Lancastrian lady to run away with him.

Such tales of chivalry and courtly love delighted the PRB so it was only natural that in 1857 Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris decide to dramatise the legend of King Arthur, his knights and the mythical Holy Grail in a mural for the debating chamber at Exeter College, Oxford, where they were studying.

The murals have darkened over the years because the artists used distemper on brick which soon deteriorated, but some of the drawings survive with enough richness of colour to give an insight into the painters’ ambition as well as their eye for a beautiful model.

One of the earliest of their female coterie, Jane Burden, the 17-year-old daughter of an Oxford stableman, posed for Rossetti as Queen Guinevere and later married William Morris, the driving force of the arts and crafts movement in the mid-19th century.

As they worked, the quest for models intensified. Rossetti wrote to a friend: “I am in the stunning position this morning of expecting the actual visit at 1/2 past 11 of a model whom I have been longing to paint for years… Did you ever see her? Oh my eye! She has sat for me now and will sit to me for Mary Magdalene in the picture I am beginning. Such luck!”

So pleased was he with the densely composed pen and ink drawing, Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee (1858), and so delighted with his model, the actress Louisa Ruth Herbert, that he gallantly (crassly?) annotated the work: ‘Stunner No 1.’

She was the epitome of the Pre-Raphaelite beauties who were definitely of a type with their tumbling hair, full lips, long neck and demure downcast eyes. Invariably too, a sense of yearning. No wonder she and the other ‘stunners’ were the object of such admiration and hardly surprising that relationships between muse and artist were forged – and lost – with high octane passion.

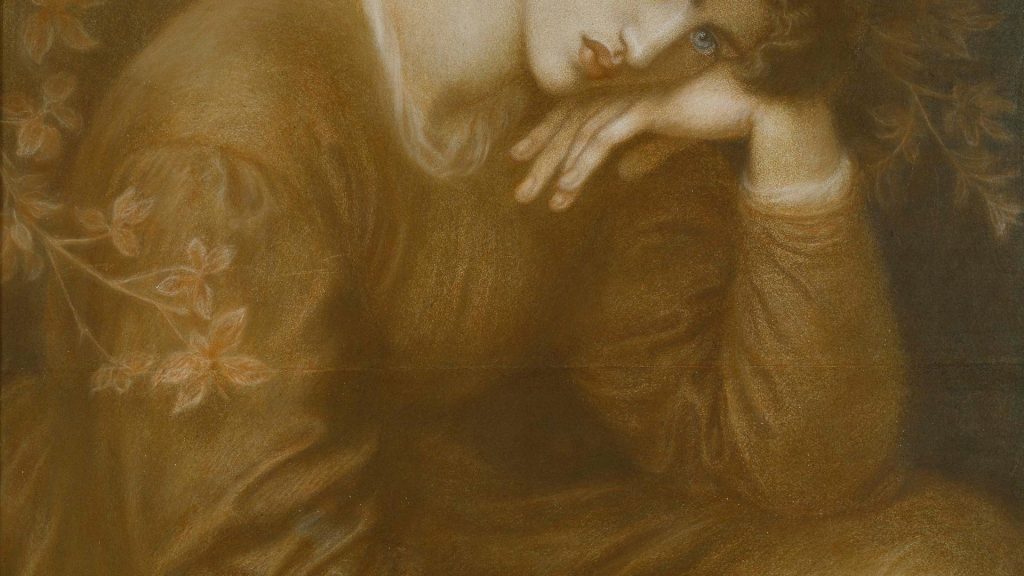

Rossetti, inevitably, romanced Jane Burden when she was married to Morris, and Rossetti movingly acknowledged their doomed affair in his sonnet the melancholy The Day Dream (1872-8) which echoes a painting of the same name in which a wistful Jane sits amidst willow trees, a traditional symbol of sorrow while holding a bind weed flower, a token of affection.

But for all the loves lost and found, painting, drawing and creating was always the PRB’s greatest passion. They were in a constant buzz of creativity, drawing each other, experimenting with different styles and sharing new techniques. Georgiana Burne-Jones wrote how husband Edward was always drawing: “He must have covered reams of paper with painting that came as easily as his breath…”

Rossetti brought the same intensity to his work with paintings which were something akin to worship. No wonder the sisterhood of muses and models were drawn to this most romantic of figures, who lived up to his namesake, the Italian poet Dante, by plunging into a very heaven and hell of romantic entanglements.

His best known muse was Lizzie Siddal who was discovered by artist Walter Deverell in 1849 when she was working in a milliner’s shop in London. He reckoned she was on the plain side, but Rossetti’s poet brother William enthused that she was “the most beautiful creature, her tall, finely formed, figure finished with a large, perfect eyelids, brilliant complexion and a lavish heavy wealth of coppery golden hair”.

Rossetti depicted her in hundreds of drawings and paintings though her most famous pose was perhaps Ophelia in 1852 for Millais. To fully dramatise her drowning in despair at Hamlet’s killing of her father Polonius, she insisted in lying in a bath and staying there even after the lights warming the water cut out. There is little doubt her hours in the freezing water contributed to the ill health which was to dog her for the rest of her life.

Her marriage to Rossetti was turbulent for, while he exalted her with his art, he was frequently unfaithful. Fanny Cornforth, for example, a blacksmith’s daughter modelled for him from 1856 and married the artist in 1862 two years after Lizzie had died suffering from depression and an addiction to laudanum.

In Rossetti’s The Portrait of Fanny Cornforth (c.1860) we see the same tumbling hair, full lips and soulful gaze that so attracted the PRB but there is something about the set of the chin, quietly assertive, which suggests that the muses and mistresses were determined to succeed in their own right.

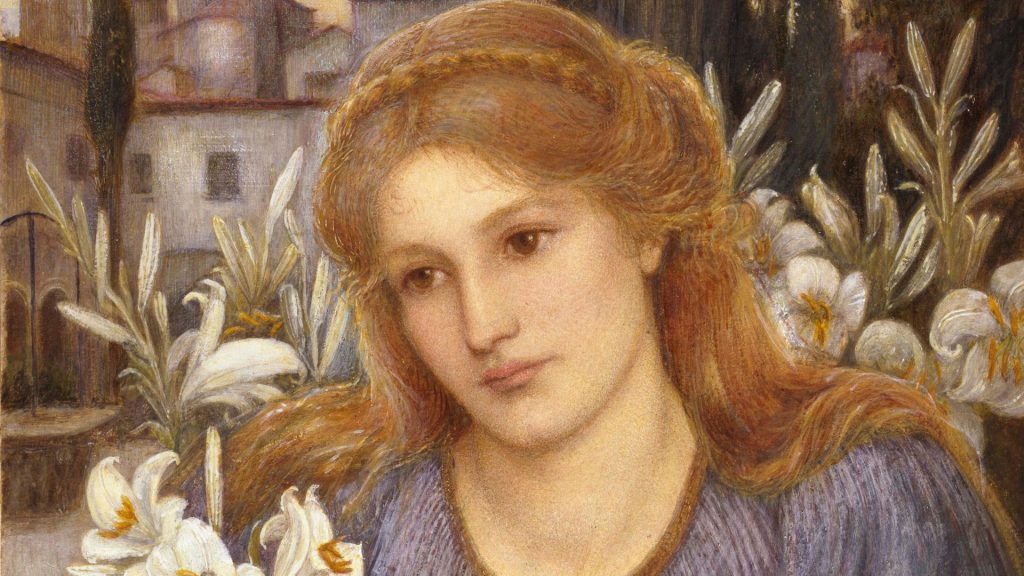

And they did just that. Ruth Herbert was already an actress of note before Rossetti dubbed her ‘Stunner No 1’ and became manager for St James’s Theatre in London. Marie Stillman modelled for Rossetti and Burne-Jones but was trained by Ford Madox Brown with such success that she created many evocative images including Cloister Lilies (1891) in which a beautiful young woman, not unlike herself, sits within the tranquil walls of a convent and contemplates becoming a nun.

Jane Morris (Burden) became a leading advocate for the revival of needlework skills which played an important part in her husband’s arts and crafts movement of the 1870s.

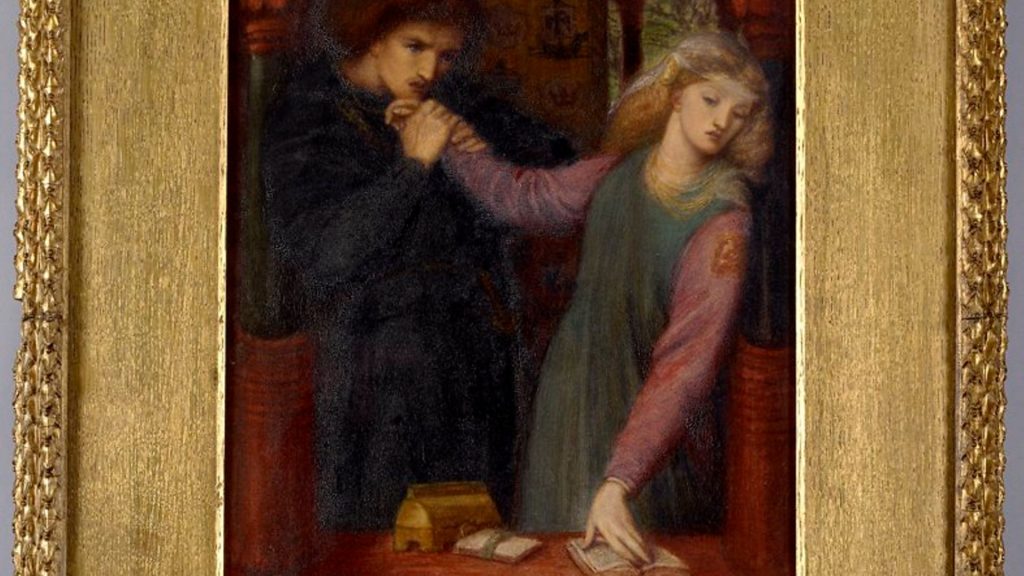

And while Siddal is known more as one of the movement’s most recognisable faces she refused to be defined by the male vision of her and was a talented poet and an artist with a simple, direct style. The Macbeths (c.1855) dramatically captures the moment Lady Macbeth takes the dagger from her husband’s shaking hands to return it to the murdered Duncan’s bedroom so the servants can be blamed for the deed.

Study for ‘Clerk Saunders’ (c.1857) was inspired by an old Scottish Ballard in which a young woman encounters the ghost of her murdered lover. It has all the drama of The Macbeths and Rossetti proudly wrote: “It is lovely… her powers of designing increases greatly and her fecundity of invention and facility are quite wonderful.”

He was even more enthusiastic about her elegant, stylised drawing Pippa Passes (1854) based on a verse drama by Robert Browning in which a young girl wanders in search of happy people but in this drawing comes across a group of prostitutes whose cynicism and mockery of the girl is in cruel contrast to her naivety.

Rossetti wrote to Browning: “I am very eager to show you this little design… in spite of immature execution I think you would agree that it is full of very high genius.”

Not bad for a ‘stunner’.

Pre-Raphaelites; drawings and water colours is at the Ashmolean, Oxford, until June 20