The architect of the Labour’s introduction of student fees says the money charged is now nothing more than vice-chancellors profiteering

By Andrew Adonis

Britain’s vice-chancellors are complaining loudly about Brexit. But the storm about to engulf them has nothing to do with Europe. It is entirely self-inflicted, the result of hubris and greed.

Tuition fees will not survive at anything like their current level. When they go, or are cut substantially from their current £9,250 level, with them go a substantial slice of the universities’ income.

The row about whether Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn did or didn’t promise to wipe out £100bn of student debt misses the point that the one thing he definitely did promise – and will again – is to abolish fees for students in future. And after his success in mobilising the youth vote last month, the Tories won’t go into the election committed to the existing penal regime of student fees and loans. The only question is whether they pledge to cut the fees or join Labour and abolish them outright. Either way, vice-chancellors need to start preparing for a big loss of income.

The root cause of the looming universities crisis is the Cameron/Clegg decision to treble tuition fees overnight in 2012. As the originator of the previous Blair government regime of fees set at £3,000 and repaid after graduation without any real rate of interest, I know how controversial it was at the outset. ‘On my tombstone will be engraved the words ‘tuition fees’,’ I told an election meeting in Nottingham in 2005. ‘Not soon enough,’ came the voice from the back of the hall.

However, the Blair reform of 2004 was a palpably fair system of co-payment, with the state continuing to make a substantial contribution to the cost of university tuition and tuition debts on graduation of £9,000 for a three-year course. It bedded down with little continuing controversy.

The overnight trebling of fees in 2010, and the decision this year to allow further increases to the fast rising rate of inflation, has now taken this figure to £27,975. In a double whammy, the interest rate on student loans was hiked to 6.1%, to help cover the escalating cost of bad debts. And this interest accumulates from the moment the student takes out the loan. So, including living costs loans, students are now graduating with debts of £60,000 and stand liable to repay up to £100,000 including interest. Oh, and the system of grants for poorer students, a key part of the 2004 system, has also been abolished. What started as a fair and modest system of graduate co-payment for the cost of higher education has become a Frankenstein’s monster of debt for the next generation.

The revolt against university fees is international. Tentative steps to introduce fees in continental Europe almost universally failed – notably in Germany, where many states introduced them at a low level only to abolish them when they became electorally contentious.

In the US, the land of mega fees, the rebellion is in full swing, started by Bernie Sanders and his pledge of ‘free tuition’. Fees suddenly became the albatross around the neck of any would-be Democrat candidate for state and national office.

Why did tuition fees get so out of hand? The trebling of the fees cap in 2010 was part of the Cameron coalition’s austerity binge in 2010, and followed sustained lobbying from the vice-chancellors that universities were still underfunded despite the 2004 reforms.

However, the bloated scale of today’s fees crisis is largely the fault of the vice-chancellors themselves, who made two crucial mistakes.

First, instead of fees varying by the cost and benefit of each course, as intended by David Willetts, the universities minister in 2010, the VCs created an effective cartel and charged the full £9,000 for virtually every course. Just in case student and parents suspected that there wasn’t really a cartel, they all increased their fees to £9,250 for virtually all courses when allowed to do so earlier this year.

So students pay as much for sociology and media studies at London Met as they do for medicine and physics at Cambridge. I doubt these London Met courses cost anything like £9,250 to lay on, so there appears to be straight profiteering.

I have referred the fees cartel to the Competition and Markets Authority and hope they break it up soon. Only the most high cost and high return courses should be charged at anything approaching the top rate.

However, as if the fees cartel were not enough, the vice-chancellors decided to go on a pay and perks bonanza with their newfound treasure, awarding themselves and fellow campus managers huge salary increases, through tame remuneration committees, despite the 1.1% pay cap for other university staff.

It’s often said top pay is only one brick in the wall and it does not make much difference to the whole edifice what people at the top are paid.

However, this is to miss the crucial point that top pay is just the apex of the pay structure, and it determines what happens across senior management within an organisation.

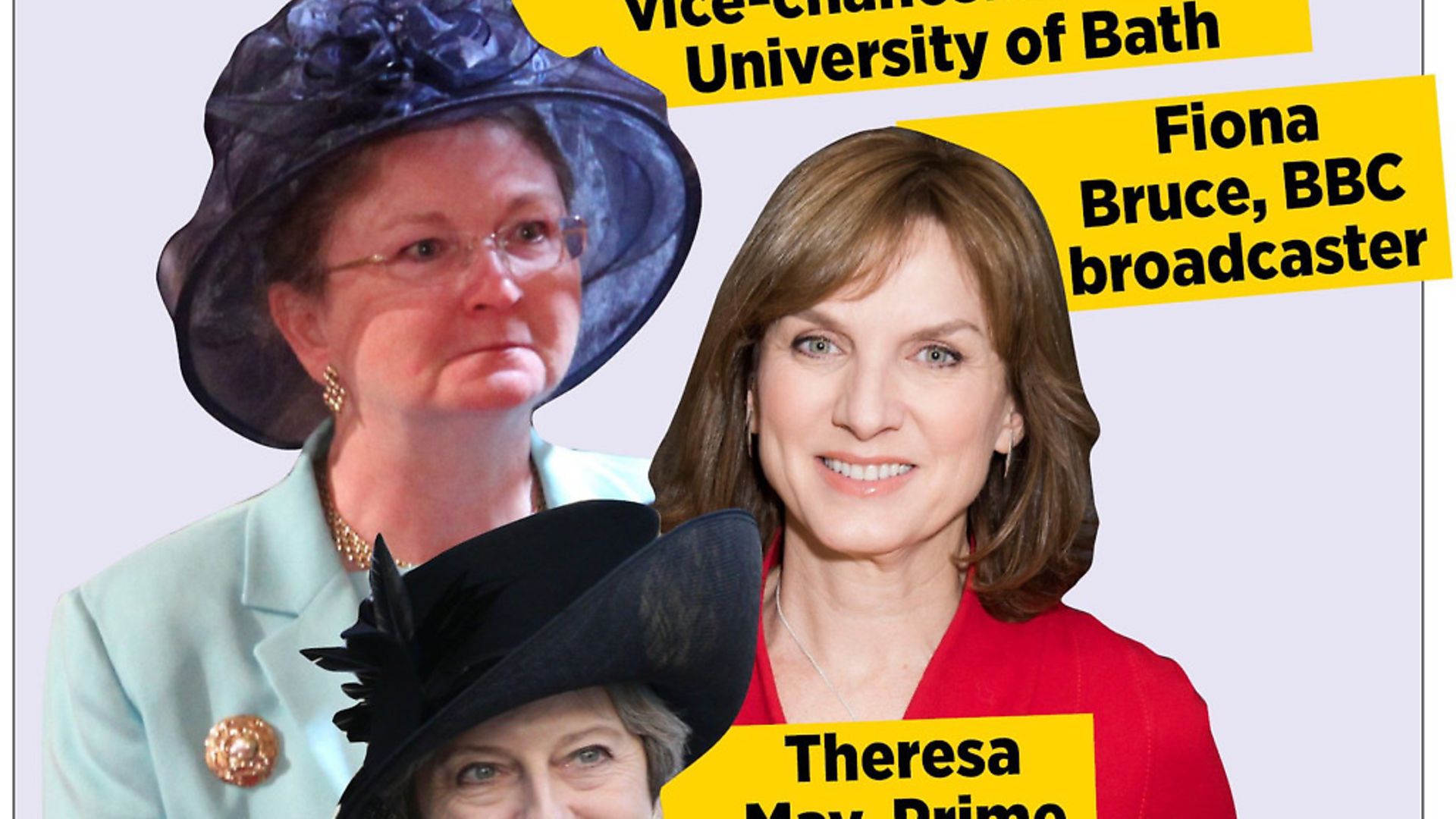

The fact the vice-chancellor of Bath university – mid-ranking among the UK’s 130 higher education institutions – is now paid a whopping £551,000, makes possible the pay of more than £100,000 for 66 other managers at Bath University.

Take those 67 salaries together, and the total is £8.7 million. That is £8.7 million out of the university’s budget of £283 million — a sizeable chunk. If that £8.7 million were halved, it would save £4.4 million — the budget of many secondary schools.

So there is a moral issue as well as a political campaign. The highly paid should set an example, particularly at a time of pay restraint and looming Brexit. The only example the vice-chancellors are setting is one of greed. That is not my idea of a university. I doubt it appeals to New Europeans either.

Andrew Adonis is a former Education Minister and the current chairman of the national Infrastructure Commission