DONALD MACINTYRE on the squealing and dealing from Boris Johnson’s government over Brexit.

We’ve been here before, of course. It was on March 13, 2003, that the cabinet were told “the message that must go out…[is] that we pin the blame on France for its isolated refusal to agree.” This was three days after Jacques Chirac had threatened to veto a UN resolution on Iraq. The exhortation was Gordon Brown’s, so the late Robin Cook says in his memoir. But Brown was certainly reflecting Tony Blair’s own view since that’s what happened: a ministerial chorus condemning France was deployed to explain why Britain was going to war without a UN resolution to underpin it.

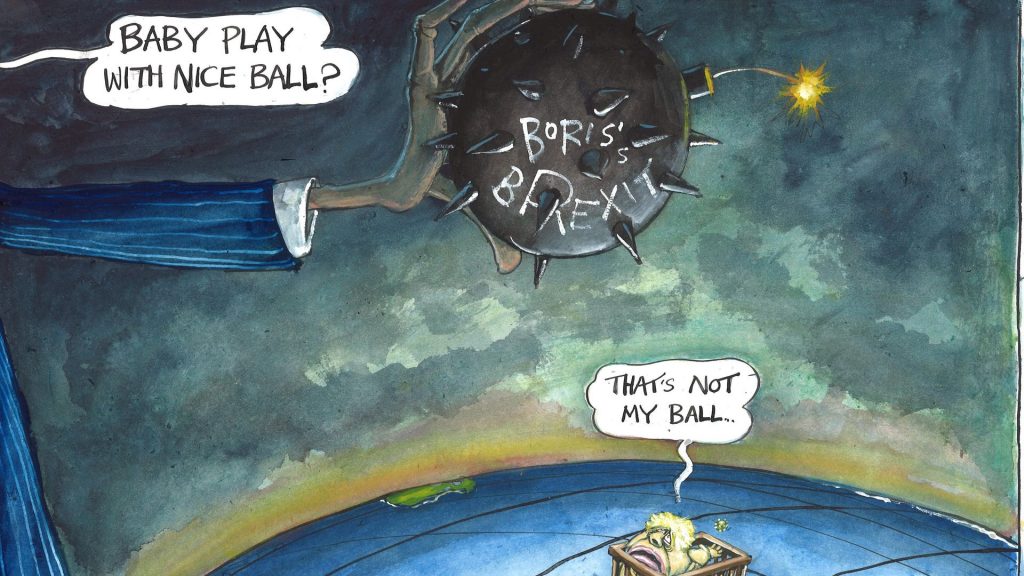

Similarly, “that sweet enemy France” (copyright the 16th century poet Sir Philip Sidney) was lined up a few days ago to take the blame in case EU-UK trade talks ended in no-deal. But this time there was an odd contradiction. Boris Johnson threatened to walk away unless he could recover the “sovereignty” stolen from its member states by the behemoth that is the EU, which, as he put it four years ago, was seeking to unify Europe under a single “authority” as Hitler did.

Yet if France did flex its muscles – even short of a veto – it would be an assertion of just that national sovereignty which Johnson implies no longer exists within the EU. President Macron was exercised over fishing – but at least as importantly over the requirement that Britain had to abide by EU ‘level playing field’ standards like those on the environment and labour, if it were to have a ‘no tariffs, no quotas’ deal. Nor was he necessarily isolated on this latter point. But the very fact that France could block an agreement, graphically demonstrates that it has – as we also had, pre-Brexit – much of the ‘control’ that we are leaving the EU to ‘take back’. You can’t reasonably argue that the power of individual member states has been eliminated by the EU and then say that just one of them has scuppered an EU trade deal.

But never mind logic. Someone would have to take the blame in the event of no-deal; France, the EU as a whole, anyone, in fact, other than the British prime minister. This was especially true given the frightening consequences of no-deal outlined in a government document leaked at the weekend to ITV News’ Robert Peston, which reads like the plotline of some dystopian sci-fi novel: 60-80% reduction in medicine imports over three months; rise in public disorder with protests and counter-protests; high seas clashes between EU and UK fishermen; reduced supply of fresh food; the poor especially hit by rises in food and fuel prices; reduced chemical supplies, disrupted energy and water; queues of up to 7,000 trucks in Kent; the loss of internal security co-operation resulting “in a mutual reduction in capability to tackle crime and terrorism”. And this is only some of it.

There was therefore something almost touching about weekend briefings that the cabinet to a man and woman were gallantly backing Johnson’s right to decide for no-deal. Those with long memories of the distant early 1970s might just recall the trade union leader Sid Greene, announcing on the eve of a long forgotten strike that “all decisions of the National Union of Railwaymen are unanimous and this one was unanimous by 13 votes to 11”. It’s a safe bet that cabinet enthusiasm for no-deal, at least in private, was equally flaky. By all accounts, departmental ministers with responsibilities for coping with the chaos resulting from no-deal, including chancellor Rishi Sunak, had become increasingly restive about the prospect. Unsurprisingly since they have had the document leaked at the weekend in their safes since September.

Nor could such an impact be buried in the admittedly dire economic results of Covid-19. In August the Sunday Times’ Tim Shipman reported on the sanguine attitude to no-deal in Downing Street that: “In the midst of the worst recession in living memory, the downsides of red tape and potential tariffs seem to many in Johnson’s team like a thimble of spit in a tsunami.”

That perception no longer seemed so sustainable after the governor of the Bank of England Andrew Bailey said last month that “the long-term effects [of no-deal] would be larger than the long-term effects of Covid”. And the November warning from the Office for Budget Responsibility that such an outcome would result in an almost immediate 2% (or £40 billion) fall in output and an additional 300,000 unemployed by the end of next year. Nevertheless, knowing to whom they owe their jobs, the cabinet members were not going to be deflected this week from pledges of fealty to Johnson by the mere prospect of a second “tsunami”.

By mid-week the hopes were that Johnson’s Wednesday evening’s dinner with Commission president Ursula von der Leyen would pave the way to some form of deal. But the febrile “will it, won’t it” speculation – and presumably, the orgy of congratulation that would engulf him if he did, have eclipsed the many adverse consequences of leaving the EU even with a deal. Not just the 4% long term loss of output predicted by the OBR even with a trade agreement. A deal would – for now – deflect the imposition of tariffs, but it would not of itself avoid the new red tape expected at borders – customs declarations, spot checks on rules of origin (whether components of goods or ingredients come from outside the EU or Britain), product safety and random food inspections – all issues for which a succession of reports, including from the National Audit Office and the Road Haulage Association, have suggested business and government are far from fully prepared. There is something in the SNP MP Pete Wishart’s gibe this week that “the oven-ready deal was in fact a barely defrosted turkey”.

On Monday the Commons restored the toxic — and in international law avowedly illegal – clauses (voted down by the Lords) of its Internal Markets Bill. The bill would have deleted the section of the withdrawal treaty which prescribes border checks between Great Britain and the island of Ireland to prevent them resuming – with potentially dire political and security consequences – on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Then on Tuesday the government, after talks between Michael Gove and the EU in Brussels, agreed to drop the clauses altogether – whether there was a deal or not. The move was bound to be seen as an olive branch, at least improving the atmosphere for Wednesday night’s dinner (while also being an imperative for the US trade deal Johnson is hoping for). But how robust would be the paper-thin EU trade deal Johnson had been seeking? Justifying his fight to escape the EU level playing field regulations, a “senior government source” explained to the Sunday Times that they would mean that “if the EU said 20 pigs could live in a sty and Britain wanted only six, Britain would have to change its rules or the EU could slap on unilateral ‘lightning tariffs’”.

On the one hand this is so much hooey; the EU prescribes minimum standards, not maximum ones. And affecting as it is to fantasise about Britain imposing tougher animal welfare rules than the Europeans, the pressure from the Europhobic MPs apparently driving Johnson seem hungry for less regulation, not more. But yes, the EU could change its minimum standards to suit itself and not a deregulatory UK government, and then insist Britain kept to them to go on trading without tariffs with the EU – its biggest market, taking 43% of its exports. Britain’s refusal to commit to future standards – rather than just present ones – went to the heart of the negotiation. But it also looked as if Britain would be paying price of being “rule takers and not rule makers” – forfeiting the leading role Britain has had for four decades in making the rules.

Meanwhile the EU have long conceded that disputes about levels of Britain’s state aid to business would no longer have to be referred to the European Court of Justice. The likeliest UK candidate to take on the job of deciding whether Britain is keeping to internationally competitive limits of state aid was the Competition and Markets Authority (though there have been doubts within the CMA about whether it is ideally suited for the role). But what happens if the CMA – or any other London body –decides that a Scottish government handout to industry is unjustified? It will be yet another grievance to boost the mounting clamour for independence in Scotland, which voted to remain in the EU.

Which brings us back to Brexit’s political risks. If the Anglo-Scottish union breaks up as a direct result of Brexit, David Cameron, who called the 2016 referendum, and Johnson, who campaigned so successfully for an ‘out’ vote, will be competing for the title of the prime minister who ‘lost Scotland’ just as their 18th century predecessor Lord North is remembered as the one who ‘lost America’. (All three went to Eton, as it happens.)

That’s apart from the drainage of British international influence. After the Russian state poisoning of Sergei Skripal in Salisbury back in 2018. Theresa May secured from the EU effective sanctions directed at Moscow. Will this go down in history as the last time Britain was able effectively to galvanise its erstwhile European partners into concerted action in its own interests?

This all finally comes down to one man. One of the most striking sentences in Dominic Cummings’ rambling 20,000-word blog for the Spectator in January 2017 on how the 2016 referendum was won for Leave was the remark that: “If Boris, Gove and Gisela [Stuart, Vote Leave’s chair] had not supported us and picked up the baseball bat marked ‘Turkey/NHS/£350m’ with five weeks to go, then 650,000 votes might have been lost.”

Cummings, was of course right to put ‘Boris’ first in what amounts to a candid admission that the campaign was won largely on its dodgiest – not to say most mendacious – claims: that Turkey would join the EU and flood Britain with immigrants and that Brexit would release £350m a week to the NHS.

But the fact that Johnson, having consistently proclaimed his belief in the European single market, dithered till finally deciding at the last minute that joining the Leave campaign would best advance his own path to power, is no longer the point.

Back in May’s time however we still talked of a ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ Brexit, reflecting that the British public had never been asked to choose between the two.

Johnson could have had the courage to face down his most extreme backbenchers and opt for a much wider and deeper deal, in the national interest, with our biggest trading and political partner. A hard Brexit was the best Johnson could hope for in Brussels.

This incidentally strengthened the case for Labour’s abstaining on any deal which was brought to the Commons. It was unlikely that a Tory rebellion against a deal would be big enough to leave the opposition with the power to decide whether it goes ahead. By abstaining it would show both that it recognises that Brexit must happen – and indeed that any deal is far better than no-deal – but that it would have negotiated – and may yet negotiate if it gets to govern – a far more comprehensive one.

But it also meant that whether Johnson failed to secure a deal and found someone else to blame, or basks in at least short term plaudits for securing one, however thin, he and he alone will finally – like Blair in 2003, perhaps rather more so – be accountable for the consequences. Whatever the final outcome of the Brussels summit and whatever the noises off, it was Johnson’s choice to bring his country to this place.

Have your say on this story and the big news stories of the week by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk. You can also continue the debate on our Facebook group.