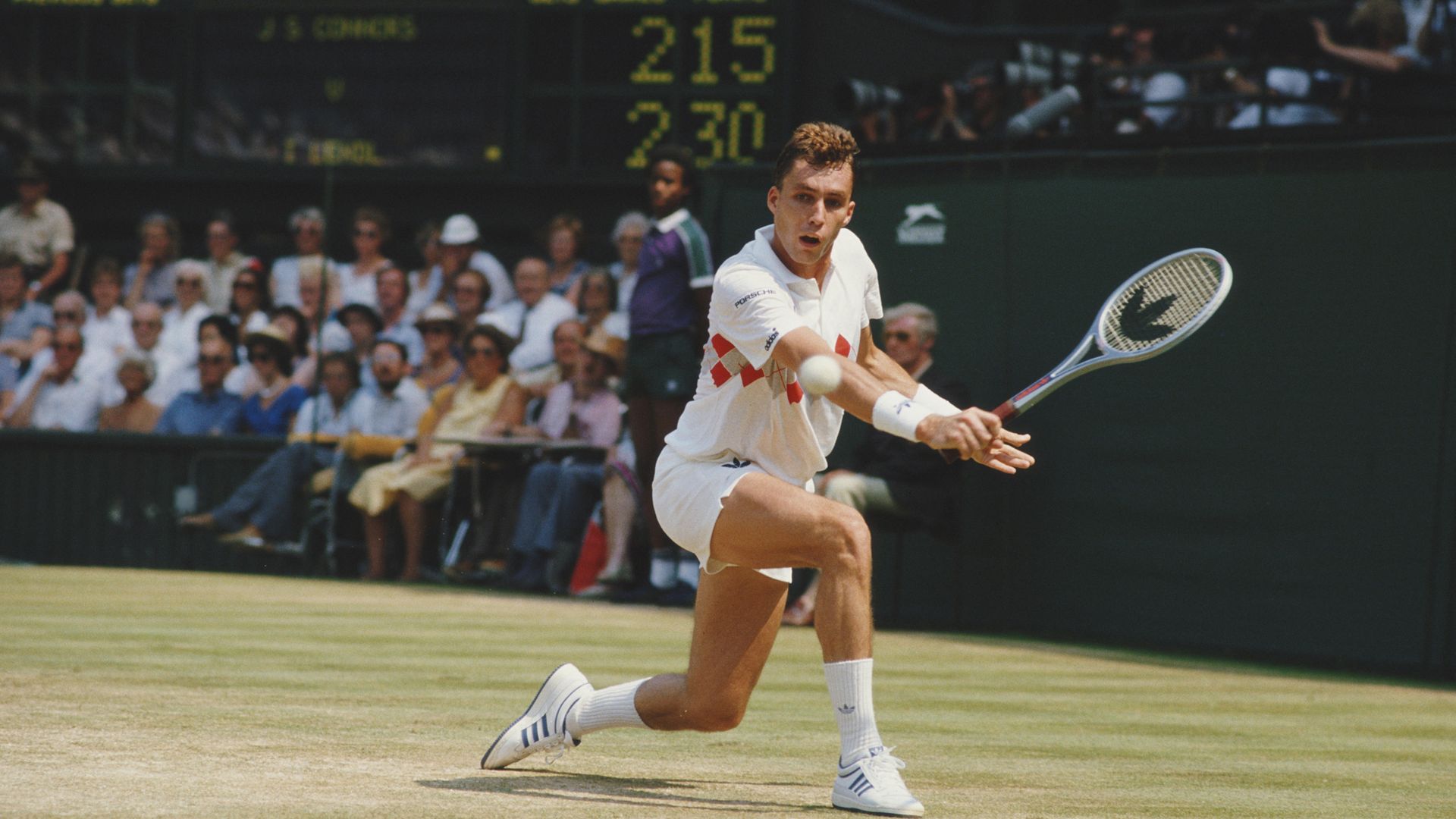

WILL SELF on discovering his DNA background and finding out he is not as closely related to Ivan Lendl as he had always assumed.

One sunny afternoon in the late 1980s I was idling my way down Sloane Street from Knightsbridge towards Chelsea when a plumber’s van screeched to a halt on the far side of the road. The passenger leant out of his window and shouted over to me: “You are Ivan Lendl, aren’t you?” I thought for a moment how best to affect a Czech accent and then called back: “Yeah, I am!” Whereupon the plumber’s mate turned to the plumber and said: “That’s ten quid you owe me.”

My resemblance to the championship tennis player used to bother me not one jot – I assumed for years that we must be distant cousins from some ur-mother or father. Lendl, like Freud, was born in Moravia – a region with a fairly large population of Ashkenazi Jews, and good son that I am, I always followed my own mother on matters of heredity. Her source for the intermarriage of Jews and Gentiles in the Pale of Settlement were the novels of Isaac Bashevis Singer – and she simply mapped this assumed miscegenation on to the rest of Eastern Europe; because she wasn’t altogether certain where our ancestors had been living before my maternal; great-grandfather pitched up at Ellis Island. For Mum, who’d seen the Nazis racialise Jewish identity as a prelude to extermination, Jewish identity was never a matter of genes: “What do Jews look like in China!” She’d expostulate: “The Chinese, that’s who!”

It remained an article of faith for her that whatever essence there was of Jewishness, it had long since been diluted by exogenous mating of one kind or another. But then Mum died before the Human Genome Project really got going, and it became possible to sequence individuals’ DNA from a saliva swab. I often wonder what she would’ve made of my own test results – obtained a couple of years ago from a company called My Heritage DNA. My Valkyrie-like daughter (six foot, white-blonde, ice-blue eyes) put me up to it, and she sent off a swab as well.

Around the time we were expecting the results back I took an Uber across town and fell into conversation with the driver. First we agreed about the pernicious nature of the gig economy – then we moved on to the appalling mismanagement of London traffic. From there – by now in deep accord – we proceeded to set the world to rights so effectively that when we reached my destination I was surprised when he didn’t get out of the car, too, and join me for dinner. I thought about this strange comity when I saw that a whopping 24.7% of my DNA was labelled – somewhat vaguely – ‘Balkan’, for the Uber driver had been Montenegrin.

Was this the brother from a different mother I’d assumed Ivan Lendl to’ve been? More perplexingly: how on earth had I acquired this exotic component to my genetic make-up? I’d been expecting Eastern European DNA – but I had none, while my daughter had 8%. She also had 19% Ashkenazi Jewish DNA – to be expected, given that I had 43.5%. But in common with me, she was not who she appeared to be: according to My Heritage 19% of her DNA was… wait for it… Iberian. Well, knowing her mother’s family as I do this was a surprise – but not that great a one. It was only too easy to imagine one of her posh foremothers, bored one day at her needlepoint, catching the eye of some swarthy Spanish gardener. But my quarter-Balkan status I found more confusing: had my Jewish ancestors stopped off there for a little rest and recreation en route to eastern Europe – and if so, for how long?

The rest of the analysis was less surprising: 19.8% Scandinavian; 6.8% Irish, Scottish and Welsh; and 5.2% English. This is pretty much what I’d expected on the basis of more visible evidence: Self is a relatively common name in north Norfolk, and its etymology is said to be a contraction of ‘sea wolf’ – the name given to the feared Norse invaders. But what about my Balkan heritage – how, in the faux-emotional discourse that typifies our era did this make me… feel?

Well, I may have known I was fooling the plumbers all those years ago, but boy did it come naturally. Was this because while I knew I wasn’t, in fact, Ivan Lendl, I did intuit that I was 68.2% ‘foreign’? (And if you include the Scandinavian component 88%.) Or was it because like a lot of people with mixed heritage I’ve always been used to ‘passing’ as a member of the majority community? Who knows, but one thing’s for sure: when we all sit down at the computer to fill out our census forms on March 21, such nuanced matters will not be captured by the fine reticulation of its tick-boxes.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk