Don’t expect to discover great depths in the paintings of Winston Churchill, but you will find the qualities that helped make him excel in other areas. Benjamin Ivry reports.

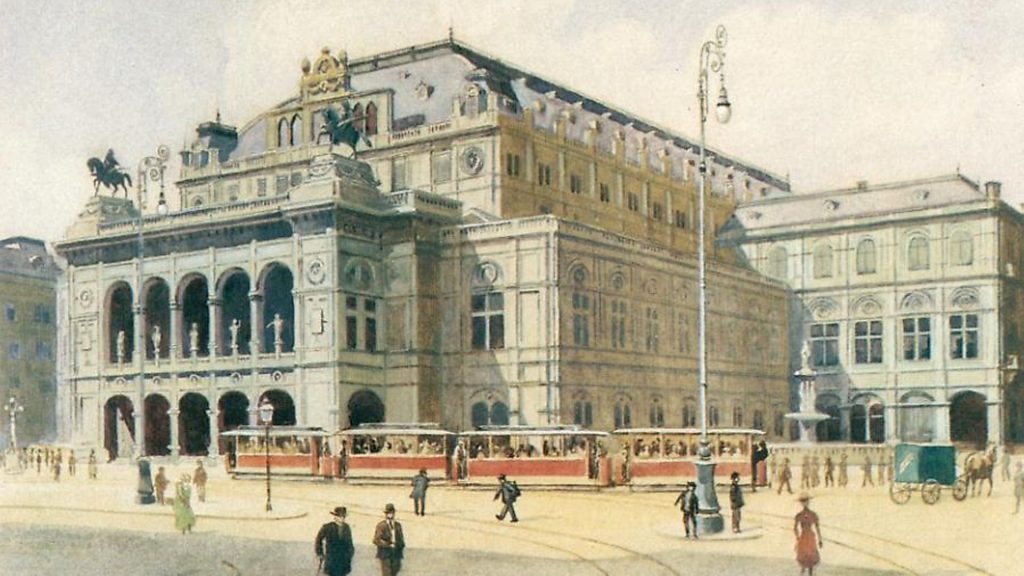

Winston Churchill has been unavoidably compared to Adolf Hitler, insofar as both were drawn to painting. Churchill’s passion for art retained an amateur status, whereas Hitler tried, and failed, to earn a living as a painter of cityscapes in Vienna. Mel Brooks’ comedy film The Producers (1968) features an addled Nazi, Franz Liebekind, who praises Hitler the painter while slating Churchill’s ‘rotten painting, rotten!’

Materially at least, Churchill’s art outvalues Hitler’s today. In 2017, Churchill’s Goldfish Pool at Chartwell (1962), described as his last oil painting, sold for £357,000 at Sotheby’s in London, over an estimate of £50,000-80,000. In 2007, Churchill’s Chartwell: Landscape with Sheep, a view of his estate near Westerham in Kent, fetched £1 million at the same sales venue.

By contrast, in 2015, a group of 14 paintings, watercolours, and drawings by Hitler fetched just over £300,000 at Weidler auction house in Nuremberg, Germany. The highest price for an individual artwork by Hitler, just over £89,000, was paid for a painting of King Ludwig II’s Neuschwanstein Castle, by a collector from China.

The question of comparative artistic value arises as well. In response, Churchill: The Statesman as Artist, a new book, has been published by Bloomsbury Continuum. Edited and introduced by David Cannadine, general editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and president of the British Academy, it contains perceptive writings about art by Sir Winston, as well as essays by art world notables who knew him personally.

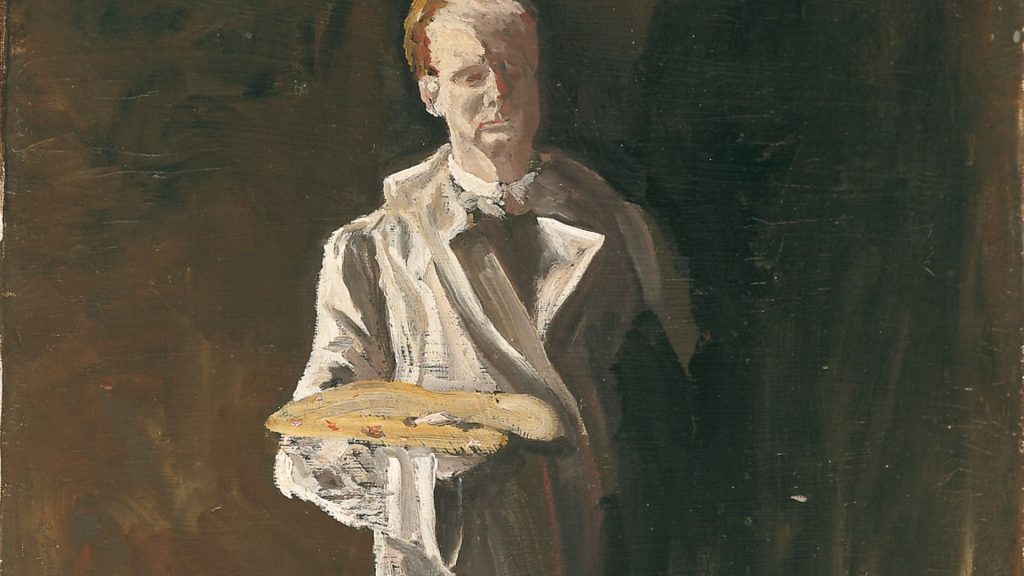

Cannadine notes that Churchill adopted painting as an intensive hobby at the age of 40. In 1915, during the Great War, after ordering what would prove to be a disastrous attack upon Gallipoli, Turkey, Churchill was removed from his post as First Lord of the Admiralty. With free time to occupy, Churchill found that painting fully occupied his mind, distracting him from recurring dark moods and anxiety that he termed black dog. His essays, especially Painting as a Pastime (1948), show that Churchill was acutely aware of how painters use vision and memory to create canvases.

The concentrated activity of painting was so joyful and essential for him that he once claimed, ‘Without painting, I could not live… I couldn’t bear the strain of things.’ Cannadine adds: ‘[Churchill] may not have been a great artist but, without painting, he might never have been the great man he eventually became.’

Until he was enfeebled by old age, Churchill was a diligent painter, leaving more than 500 canvases. This is an impressive number, considering the books he found time to write, apart from his political and government activities. He would claim that a half-hour spent standing to salute soldiers on parade or to worship in church were fatiguing, whereas no one could be tired by standing for three hours to work on a canvas.

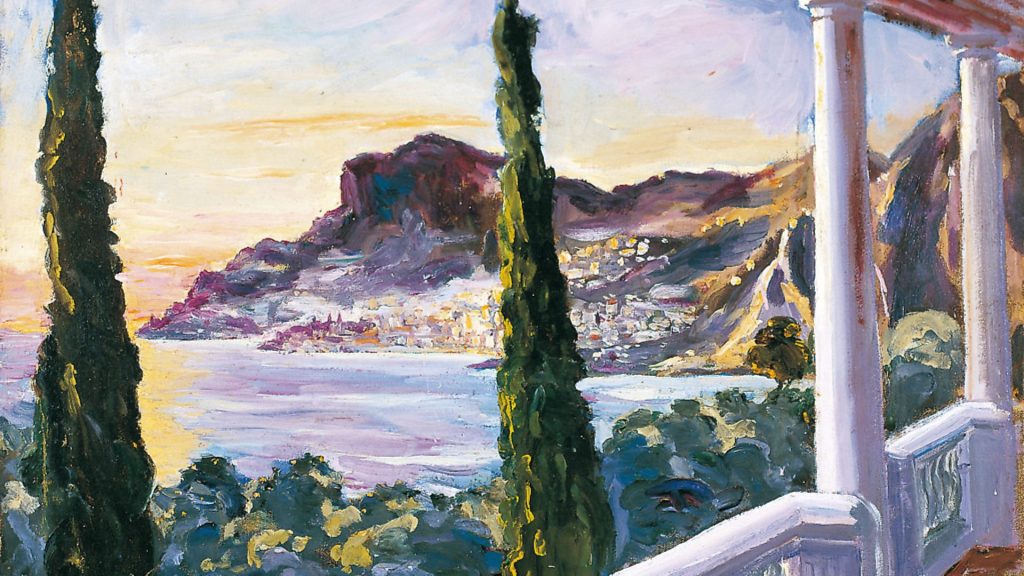

And the quality of his works? Churchill was an amateur painter, much influenced by the Impressionists. He was moved by sun and light, following in the footsteps of such French predecessors as Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Churchill’s own near-contemporary, Henri Matisse.

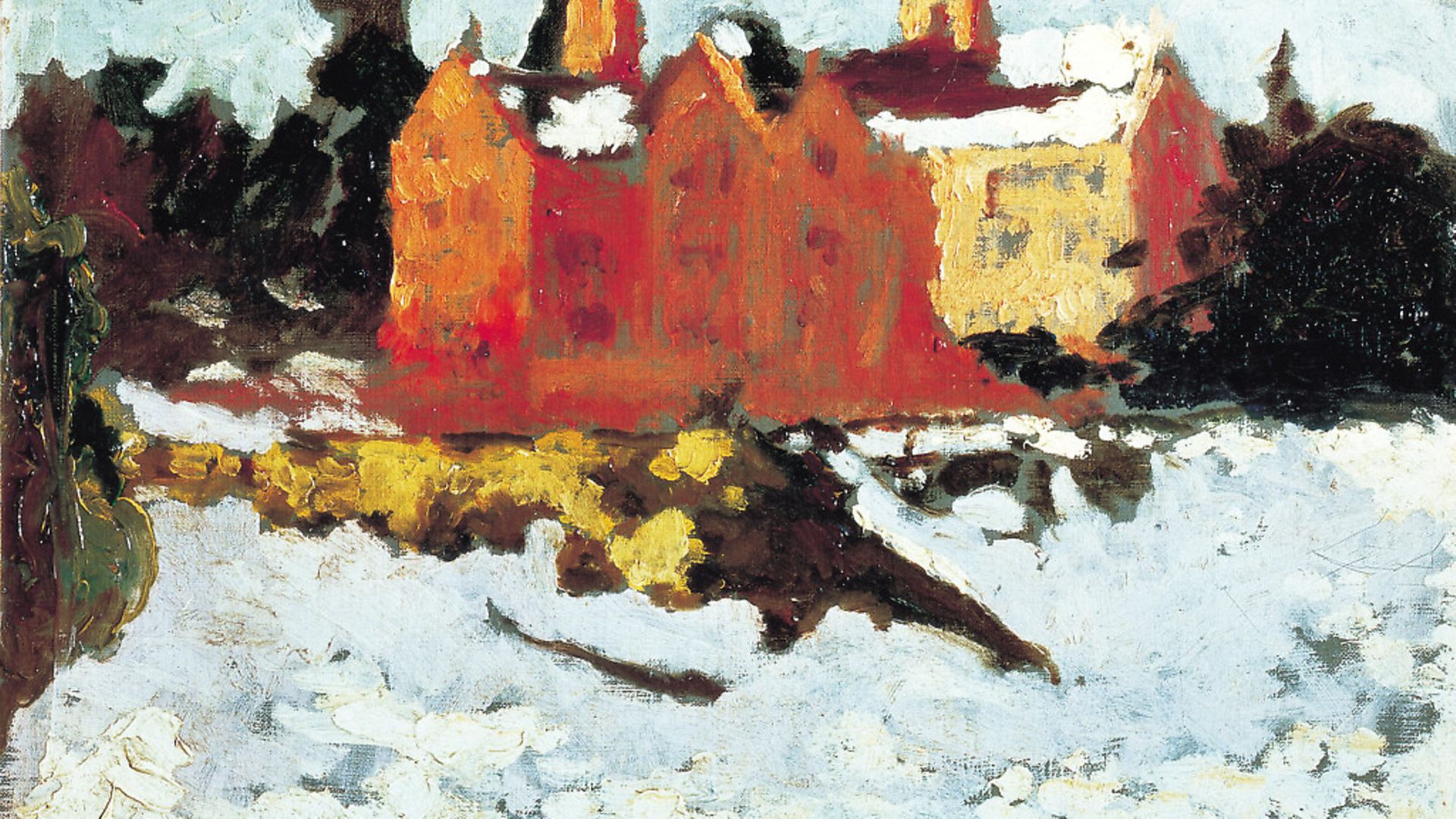

In such typical Churchill landscapes as Harbour, Cannes (1933) and Château St-Georges-Motel (c.1935), the water is rendered far more vividly, and indeed impressionistically, than any buildings.

By contrast, Churchill’s attempts to reproduce architecture often resulted in lumpy edifices, awkwardly asymmetrical. But water, light, and air were his ideal domains, and these he celebrated ardently. In Painting as a Pastime, he observed that to reproduce nature as a ‘mass of shimmering light’, it was necessary to use ‘innumerable small separate lozenge-shaped points and patches of colour – often pure colour – so that it looked more like a tessellated pavement that a marine picture’.

Cannadine, although no art critic, asserts convincingly: ‘Churchill was not a great artist, but he was a very accomplished painter, whereas Hitler had no talent whatsoever.’ The Nazi dictator’s finicky, rigid, oddly powerless daubs might appeal to Chinese collectors, but otherwise find no serious admirers among art connoisseurs.

Another fascist dictator, Spain’s Francisco Franco, while less prolific than either Churchill or Hitler, created realistic genre scenes of hunting and the like, expressing dark sadism, as in one canvas of a bear being attacked by a pack of hounds, ripping one apart.

Paintings were also created by American President Dwight D. Eisenhower, reportedly in emulation of Churchill. Eisenhower’s simplistic efforts are primitive or naïve art in the worst sense of those terms, possibly even worse in quality than Hitler’s. Then there are the more recently publicised paintings by American President George W. Bush. The 43rd president of the United States created portraits of world rulers that were displayed in a 2014 exhibit, The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy, at Bush’s Presidential Library in Texas. Bush’s paintings were closely based on photos of all the subjects, found on Google and Wikipedia.

Bush’s artworks have some of the cartoonish superficiality found in works by Andy Warhol or the young David Hockney, influenced by pop art. Inexplicably, in 2014 the director of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston likened Bush’s paintings to those of the Russian-French painter Chaim Soutine.

To put it mildly, Soutine was a major contributor to Expressionism, whereas George W. Bush was emphatically not. Yet for a Texas art world professional, dismissing artworks by a former president might be as uncomfortable as it would have been for any of Churchill’s admiring contemporaries to scorn his painting hobby.

Fortunately, he did rise above the morass of delinquent and risible pseudo-art by other leaders. No other ruler-painter of the past investigated the art of his day, consulting with major authorities in order to weigh their advice, as Churchill did. His inquisitive, questing approach resembled his fact-finding missions about public matters involving life and death.

To better understand the challenges of making art, he studied the Victorian art criticism of John Ruskin and other writers. Yet no matter how seriously Churchill took painting, even during his lifetime, there was disagreement from experts about how to cope with the resulting artworks.

In 1958, a touring exhibit of 35 canvases by Churchill was shown at Kansas City’s Nelson Gallery of Art, later travelling to Washington DC’s Smithsonian Institution and New York’s Metropolitan Museum. But distinguished museums in Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Cincinnati, refused to display the exhibit.

Cannadine recounts, possibly with tacit outrage, that the museums demurred ‘on the grounds that Churchill’s works were of insufficient merit or originality’. Just two decades ago, when a group of more than 100 works by Churchill were assembled for an exhibit at Sotheby’s in London, the art critic Brian Sewell declared that the selection was a ‘load of bloody rubbish’.

Perhaps taken in bulk and assessed without biographical or historical context, Churchill’s canvases will always disappoint a section of the professional art world. Yet some of the most percipient art historians have been beguiled by his creativity. A case in point, omitted from the Bloomsbury Continuum volume, is Winston Churchill as Painter and Critic by Sir Ernst Gombrich, originally published in The Atlantic in March 1965.

A dazzlingly insightful art historian, E. H. Gombrich monitored German radio broadcasts during the Second World War for the BBC World Service. In 1945, when a Nazi broadcast was prefaced by Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7, written to commemorate the death of Richard Wagner, Gombrich deduced that Hitler had died and broke the news to Churchill.

Sympathetic but never in thrall, unlike other former Churchill associates, Gombrich identifies the great man as an amateur or dilettante from a generation of realistic painters. They all expressed the ‘joy of painting boldly in strong colours… What mattered increasingly was spontaneity, boldness and a certain freshness of vision that was summed up in the catchword of the innocent eye.’

Boldness Churchill certainly had, making up for a lack of expertise that might be expected from a full-time professional artist. As he put it, for those who ‘go on a joyride in a paintbox… audacity is the only ticket’. And for this genre of art, this attribute went a long way, making his canvases more palatable than they otherwise might have been.

Gombrich further admires Churchill’s mental preparation and self-analysis as an artist. The psychological challenges of perception and reproduction of nature in art were bravely embraced by Churchill. As he was to some extent self-medicating with the hobby of painting, part of his therapy was understanding the effects of the leisure-time activity upon his body and mind. To this end, Churchill described his start in painting as a scene of violation committed upon an ‘absolutely cowering canvas. Any one could see that it could not hit back… The sickly inhibitions rolled away. I seized the largest brush and fell upon my victim with Berserk fury’.

Gombrich cautioned anyone who sought to read too deeply into Churchill’s art for evidence of his inner feelings: ‘It may be argued that these correspondences between a personality and its expression are both trivial and deceptive. Hitler, the screaming demagogue, painted tame water-colours. No doubt these too reflected one side of his character. He would not have painted them otherwise. But nobody could learn much worth knowing about either of the protagonists of World War II from a contemplation of their works.’

Even if Churchill’s paintings themselves are not a direct expression of himself to the extent that a professional artist’s necessarily would be, he went about creating them in a quintessentially Churchillian way.

Gombrich adds: ‘He took up the new hobby with that zest that was all his own and grasped the whole situation with a clarity and an insight that mark the great statesman and historian.’ For this reason, art looks likely to continue as an indispensable part of his legend, with the brandy, cigars, soul-inspiring speeches, oratorical skills, and the rest.

Even Mel Brooks might concede that Churchill’s paintings were part of what made him such a storied leader at a time of historical crisis for Britain and the rest of the civilised world.

Churchill’s Contemporary Artists

Hitler produced hundreds of paintings when trying to earn a living as an artist in Vienna, in the years leading up to the First World War. He sought admission from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in the 1900s but rejected twice.

Franco’s painting pastime is less known. This secret hobby came to light in 2011, with the publication of a book by his grandson, who described how Caudillo had been encouraged to paint by his personal physician, as a way to relax from the stresses of governing.

In the book, 15 artworks were reproduced, including a self-portrait of the late Spanish dictator wearing military uniform and holding binoculars, and scenes depicting hunting and sailing, two of his favourite pursuits. The final canvas attributed to Franco is of a sailing boat sinking in stormy waters.

Dwight Eisenhower took up painting in earnest in 1948. He is said to have been encouraged to take his hobby more seriously by Churchill – although – like Franco, he may have been following doctor’s orders in using the activity as a means of stress relief.

Eisenhower, who became US president in 1953, claimed he had the most opportunity to paint when he was in the White House, because his time was so well managed. he would sometimes present ‘paint by number’ kits to visitors to the Oval Office.

At his Gettysburg home, the porch became the painting studio. ‘Ike’ produced 260 paintings during the last 20 years of his life.