From 18th century to Russell Brand and Owen Jones, Sarah Ditum explores the history of ‘brocialism’.

Half a century before The New European became The New Feminist (for this week, at least), there was the Rat.

Part of New York’s radical press, the Rat combined left-wing politics with nudie covers and pornographic cartoons – directed, of course, by a male staff. In January 1970, a group of feminists ousted the editorial team and turned the paper over to their own concerns. This was where Robin Morgan first published her essay Goodbye to All That, a ferocious blast against the sexism of the left: ‘Goodbye to the male-dominated peace movement… Goodbye to the illusion of strength when you run hand in hand with your oppressors… Goodbye to Hip culture and the so-called Sexual Revolution.’

Morgan didn’t imagine that the men considered the Rat takeover significant. (‘What the hell, let the chicks do an issue; maybe it’ll satisfy ’em for a while, it’s a good controversy, and it’ll maybe sell papers’ runs an unoverheard conversation that I’m sure took place at some point last week,’ she wrote.) But to the feminists, it mattered because Rat represented the ‘good guys who think they know what Women’s Lib, as they so chummily call it, is all about – who then proceed to degrade and destroy women by almost everything they say and do.’ Rat stood for the political world where Stokely Carmichael could joke that ‘the only position for women’ in activism ‘is prone’, and where Eldridge Cleaver could write about raping women as an ‘insurrectionary act’ against the ‘white man’s law’. What Morgan took aim at in Goodbye to All That is what today I’d call ‘brocialism’ – a dismissive portmanteau of ‘bro’ and ‘socialism’ which describes the meeting place between left-wing ideology and virulent machismo.

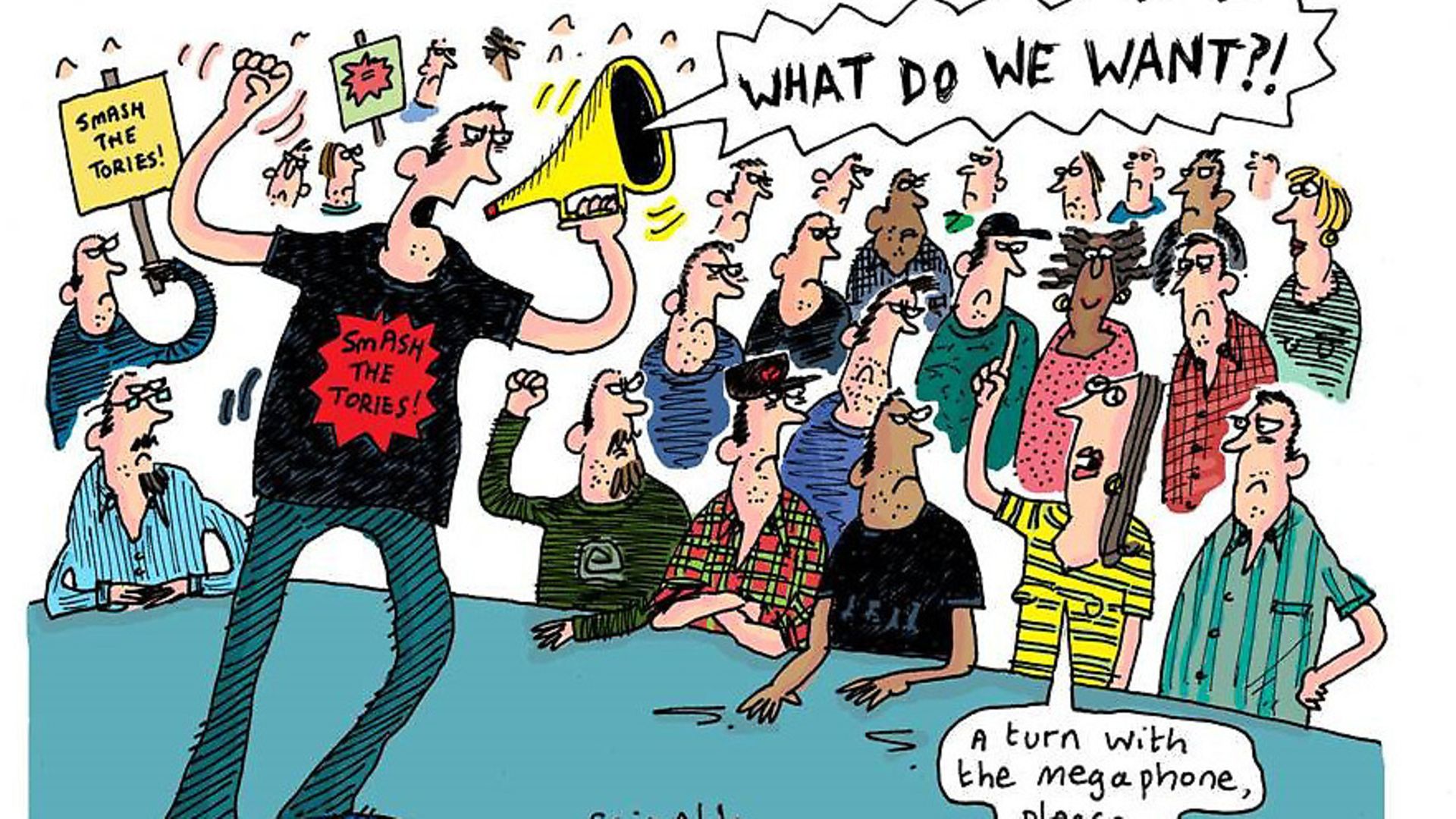

Brocialism is the politics of the left that puts women last. Brocialism is when it just so happens, coincidentally, that the politicians who attract the most hatred for being ‘right-wing’ are also the female ones. Brocialism is saying we’ll get around to sex equality, but the revolution comes first.

Brocialism is sneering at middle-class women for hiring cleaners, but not at middle-class men who expect their wives to pick up their dirty boxers for free. Brocialism is the men who call themselves feminists, but seem to be more interested in telling women what they’re doing wrong than in giving up any of their own power. Brocialism is blaming the EU for depressing men’s wages – but not acknowledging that the EU has driven workers’ rights for women.

Brocialism is Owen Jones telling women who disagree with them that they’re on the ‘wrong side of history’. It’s Russell Brand offering a revolution in which women figure firstly as ‘your bird’. It’s the American Democrats who were so wedded to Sanders over Clinton that they ultimately helped to ensure that Trump won. It’s the men who sexually assaulted women in the Occupy camps, and the kangaroo rape trials of the Socialist Workers Party. It’s the abuse and death threats thrown by Corbyn supporters at female MPs deemed insufficiently loyal to the cause, such as Luciana Berger or Thangam Debbonaire. It’s Jeremy Corbyn wanting to overthrow capitalism, until it comes to women being prostituted, when he says that the only ‘civilised’ option is a free market.

It’s also a tediously old phenomenon. When Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Men in 1790, it was because she was wholly committed to revolution. She followed it with A Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1792 because she’d realised that revolution was a male-only affair. ‘Consider,’ she pleaded, ‘whether, when men contend for their freedom, and to be allowed to judge for themselves, respecting their own happiness, it be not inconsistent and unjust to subjugate women.’ It was not considered. As historian Rachel Hewitt explains, the woman question in the 18th century was fought mainly between the reactionary position that ‘a woman was the property of one man’ and the radical belief that ‘she was the property of many’.

The same false choice persists. From the right, low-income women are coerced to remain chastely within the family (Iain Duncan Smith designed Universal Credit so that it would be paid to a single recipient in each household in order to ‘prevent family breakdown’, or, rather, stop women from leaving). From the left, the men at the top of the Labour Party propose full decriminalisation of prostitution – that is, not only ending the unjust criminalisation of women in prostitution, but also lifting all sanctions on the pimps and punters who exploit and endanger those women. For women, this means either having one master, or having several. There is no alternative here to subjugation.

Yet left-wing politics is supposed to offer alternatives. As the Scottish socialist Alasdair Gray wrote, it’s animated by a belief in possibility: ‘Our nations are not built instinctively by our bodies, like beehives; they are works of art, like ships, carpets and gardens. The possible shapes of them are endless.’ Feminism shares that belief, which is why the movement’s key thinkers and activists have often (though not always) come from a radical or socialist background: because feminism is, ultimately, a radical project and a redistributive one. It is about claiming rights and recognition for labour: the unpaid domestic labour that’s worth 56% of GDP and of which women do 60% more than men; the labour of bearing and caring for children, without which there would be no people and no economy at all.

It is about taking away from men the unjust power they assert over women, and giving women authority over themselves. It is difficult to articulate just how transformative that would be. The sex-class system is so entrenched that people still clutch at the belief – despite all evidence – that something in our essential nature makes women domesticated and decorative, and men bold and competitive.

In The Dialectic of Sex, Shulamith Firestone described how ‘so profound a change cannot be easily fit into traditional categories of thought… not because these categories do not apply but because they are not big enough: radical feminism bursts though them. If there were another word more all-embracing than revolution we would use it.’

And this is why the left has ultimately so often failed to give feminism a home: because, whatever their position on the left-right spectrum, too many men have been and still are unwilling to surrender the dominance they have over women. Feminism has always stood against right-wing chauvinism, but frustration with the macho left has helped to form much of the women’s movement’s most important theory and activism.

Realising the limitations of men’s politics shaped the proto-feminism of Wollstonecraft. Morgan and Firestone and their peers found the fervour of the second wave when they despaired of their male comrades. In the 19th century, women workers unionised not only to contend with their bosses, but also so they could resist male trade unionists who complained of ‘unfair female competition’. Feminist separatism has been out of favour for some time.

Labour’s all-women shortlists transformed the demographics of the UK parliament, and put women’s issues on the mainstream agenda. It even looked, briefly, as though the Democratic Party would bring forward the first female US president. But before Hillary Clinton could win the presidency, she had to win the candidacy, and to do that she had to defeat Bernie Sanders. And many people on the left – specifically, many men on the left – did not want her to do that. Her experience was cast, not as proof of her abilities, but as discrediting insiderism.

At Rolling Stone, influential left-wing journalist Matt Taibbi called her part of an ‘inexorable pattern of corruption’, and credulously repeated the same insinuations about her emails that Trump would go on to use against her. Well, perhaps Taibbi was simply prescient about her weaknesses as a candidate. But later on, as #MeToo gained force in 2017, stories about Taibbi’s past conduct emerged. In the 1990s, as co-editor of Moscow-based English-language paper the eXile, Taibbi had attacked and objectified women and girls, celebrating a cowboy capitalism world where women were for sale, gleefully attempting to trash his female colleagues’ careers.

Women should not wear trousers and flats, he wrote: they should be like Russian women, with ‘tight skirts, blowjob-ready lips, and swinging, meaty chests’.

It’s not a surprise that a man who wrote like that about women should be so keen to find fault with Clinton’s candidacy. What is shocking is that, with this evident and explicit misogyny, Taibbi was not only indulged by the left but elevated to a position where he could sway Clinton’s presidential prospects. And then, to compound the insult, left-wing men (including Bernie Sanders) decreed that Clinton had lost to Trump not because of sexism, but because of her focus on ‘identity politics’. Men had made her sex the issue, and then they blamed her for the focus on her gender.

We’ve seen this before. In 1984, Geraldine Ferraro had broken her own glass ceiling by becoming the first Democratic candidate for vice-president. Like Clinton, she was attacked in grossly personal terms and with spurious scandals. Like Clinton, her gender was decreed the ultimate cause of the Democrats’ loss: ‘Democratic party leaders charged that women were responsible for the party’s poor showing and that women had had too much influence in the campaign and were driving away white men,’ reported Susan Faludi in her 1991 book Backlash.

The Ferraro effect set back women on the left for decades. In 2018, women cannot afford to be cut out of politics. The shape of the UK after Brexit is being driven by men, and on the left, that means a pursuit of ‘Lexit’ which gives no thought to how women will be affected. It’s time for a takeover.

Women should look at what the brocialist left is offering – the sexist abuse, the devaluing of women’s work, the absence of any alternative to a male-dominated society – and say, like Morgan, goodbye to all that.

Sarah Ditum is a critic and journalist who writes for the Guardian, New Statesman, Spectator, Lancet and others