Since Brexit, the British government has given the impression that the country’s manufacturing future depends on a brave new leap forward into green technology, which it would support with huge grants, political commitment and a serious industrial policy. That new policy would inevitably involve being open to other markets and the global economy.

Big technological shifts tend not to happen in one country alone. To move ahead into the green, lithium ion battery-powered future means being economically open and welcoming. But increasingly, it seems, Britain is not open for business. Quite the opposite. In the face of persistent failures, the government is reduced to raising its hands and saying: “Nothing to do with me, mate.”

Even after 13 years of total incompetence, the Britishvolt debacle stands out. The collapse of the battery manufacturer falls so far below the standard of even this government that it is difficult to grasp the scale of the failure. It also shows the immense damage that can be caused when a country like Britain cuts itself off from its neighbours, in the delusional hope of going it alone. Now, unless Britain can build several massive new battery factories, the British car industry is finished. The collapse of Britishvolt means the date of the industry’s execution has most probably been brought forward. It turns out that slamming the door on your closest economic partners has consequences. Who would have thought it?

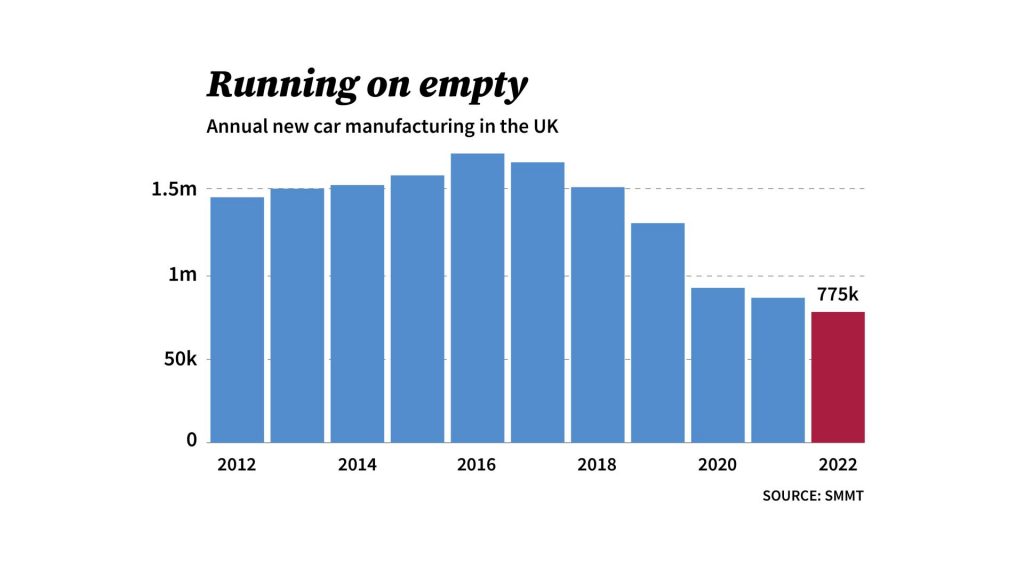

Production of new diesel and petrol engine cars will become illegal in the UK by 2030, as part of the government’s commitment to fighting climate change. Over the next seven, short years, the whole car industry will have to invest billions in new technology, new designs, new facilities, new production lines and new suppliers. If it does not do this, production in the UK will cease. British car production is already at its lowest level since 1956, in part because of a shortage of microchips, but also because several car plants have closed and new investment is not coming into the UK. The impending battle between the EU and the US over subsidiefmans for green industries will leave the UK out in the cold, with an automotive sector withering on the vine.

Britishvolt is the perfect example of the madness of “Global Britain”. The UK has been left isolated and alone on the edge of a continent. Its only chance of making something of the mess was to develop a radical, huge and well-funded economic and industrial policy, to attract firms despite Brexit, to nurture the industries of the future, to soften the blows of Brexit, or at a bare minimum to just have a plan. It did none of these things, and Britishvolt is the result.

It was one of those very British, go-it-alone, overly optimistic to the point of delusion, underfunded, naive ideas. Britishvolt was designing its own batteries from scratch, yet it did not have any previous experience of making batteries. Neither did it have any customers.

You might think that the bare minimum requirement to make a success of such a venture was to have a cast-iron deal, an approved design, agreed funding and a ready buyer – and you would be right.

The scheme was also fantastically underfunded. The UK government had committed to a mere £100m of support, to be released if and when Britishvolt actually met certain bare minimum requirements, such as starting to build a factory and attracting private finance. But even last year it was clear the company was running out of money and the government never contributed a penny. The ambition to turn a start-up into a multibillion-pound manufacturing giant that could compete with huge multinationals fell at the first hurdle. Britishvolt went belly-up without even making a single battery. That is pretty pathetic for a company that claimed it would build a £3.8bn factory, employ 3,000 workers and supply 25% of all the batteries needed by the British car industry.

None of these obvious flaws stopped the then PM, one Boris Johnson, from claiming Britishvolt was “fantastic news” and – you’ll like this one – that it assured “the UK’s place at the helm of the global green industrial revolution”.

All of it was just a shameless attempt by the blustering buffoon to get on the battery-powered bandwagon. All of it was complete bullshit.

Brexit made the future of the British car industry insecure even for conventionally fuelled vehicles. The supply chains are huge and crisscross Europe, often many times. A major component can travel into and out of numerous countries and factories before it is installed on the final production line, and it is all done just in time. There is no spare capacity, no spare parts are stored on site and there is no room for delays. That means that Brexit red tape, costs and checks at the border all make UK plants less attractive.

Now, on top of that Brexit has placed another giant millstone around the industry’s neck. Rules-of-origin regulations mean that because the car battery is such a huge percentage of the cost of an electric car, only electric cars made with European or UK batteries will escape tariffs on their import into the EU. For the UK car industry this is a disaster – batteries imported from Asia or America and put into cars in the UK will face import duties, making them completely uncompetitive.

Carmakers must either have a UK-made battery or import one from the continent. But the cost of importing batteries is very high. The simple reason why the EU and its member states are building huge battery capacity is that they want and need it to be where the car factories are. The Faraday Institution calculates that there will be demand for seven UK-based gigafactories by 2040, each producing 20GWh per year of batteries. With little sign of that happening, it looks as if we will either have to import batteries, or else the industries that need them will die – or simply move to the EU.

The UK had already fallen far, far behind its competitors in battery technology and capacity. Elon Musk is building his European gigafactory not in the UK, but in Berlin. Why? Because, as he told the world, Brexit made the UK “too risky”.

China, America and the EU have invested billions in developing and attracting battery production. In comparison, the UK has done and got virtually nothing. Only Nissan has attracted a Chinese company to build its batteries near its Sunderland plant, while on the continent the car industry is building new battery capacity in a strategically targeted attempt by the EU to take on the world.

To put it more bluntly: Brexit means that unless the UK government can wish up several gigafactories the same size or even bigger than the collapsed Britishvolt, the UK’s car industry is probably doomed. If the UK government was serious about saving it, then it would have to do what the EU is doing and spend billions on a strategy. Instead it promised £100m, which it never paid, to a start-up that went bust.

At the same time that ministers were boasting that Britishvolt was a sure sign that Global Britain was attracting the brightest and best to its shores, the rest of the world was looking at the country and making a hard-headed decision. It decided to invest almost anywhere but the UK.

The UK’s current plans mean it will have just 26.9 GWh of capacity by 2031. Even with Britishvolt, the UK would have been only the eighth largest battery maker in Europe behind Spain, Poland, Norway, France, Sweden, Hungary, and Germany. Now Britishvolt has gone, the UK slips to 10th place behind even Italy and Portugal. Germany alone plans to have 378 GWh of capacity by 2030 – 14 times the UK’s.

Car manufacturing is important to the British economy. In 2021, 800,000 cars and 1.6m engines were made in the UK, of which 80% were exported. The industry accounts for 10% of all UK exports and employs hundreds of thousands of people directly and indirectly. All of that is at risk.

Electric vehicle car manufacturing is just one sector of the British economy that Brexit is making far worse. But it is a huge one, and it sets a frightening precedent.

Britishvolt is not just a failure in its own right, it is a harbinger of what is to come. The companies and the countries that can master green technology will own the future; ending reliance on fossil fuels, the ability to create, distribute, store and use green electricity is the new industrial revolution.

A real government with real policies would be working night and day to fund research, attract companies, grow new industries, build infrastructure, cooperate with industry, give seed capital to start-ups, subsidise new skills and technology, build national champions, coordinate investment, create strategic partnerships, and provide finance. Certainly, that is what China, the EU and the US are doing.

The failure of Brexit makes such policies more important, not less. But tragically Brexit was promoted by economically illiterate, ultra-freemarket, small-state, know-nothings. So the UK gets the worst of both worlds. It is not part of the EU plan to build the world-beating industries of the future, and it has no industrial policy of its own.

Battery-powered vehicles are the future of the car industry, but many more things are going to be battery powered, green and high tech very soon. Green technology is the future for the world’s manufacturers. Being at the forefront of this change is not just about guaranteeing you have a car industry in seven years’ time, it is about ensuring you have any industry.