“Strain every nerve, parents of Britain, to send your son to this educational establishment… Exercise your freedom of choice because in this way you will imbue your son with the most important thing, a sense of his own importance.”

Boris Johnson, writing for The Chronicle, Eton’s student magazine, aged 16.

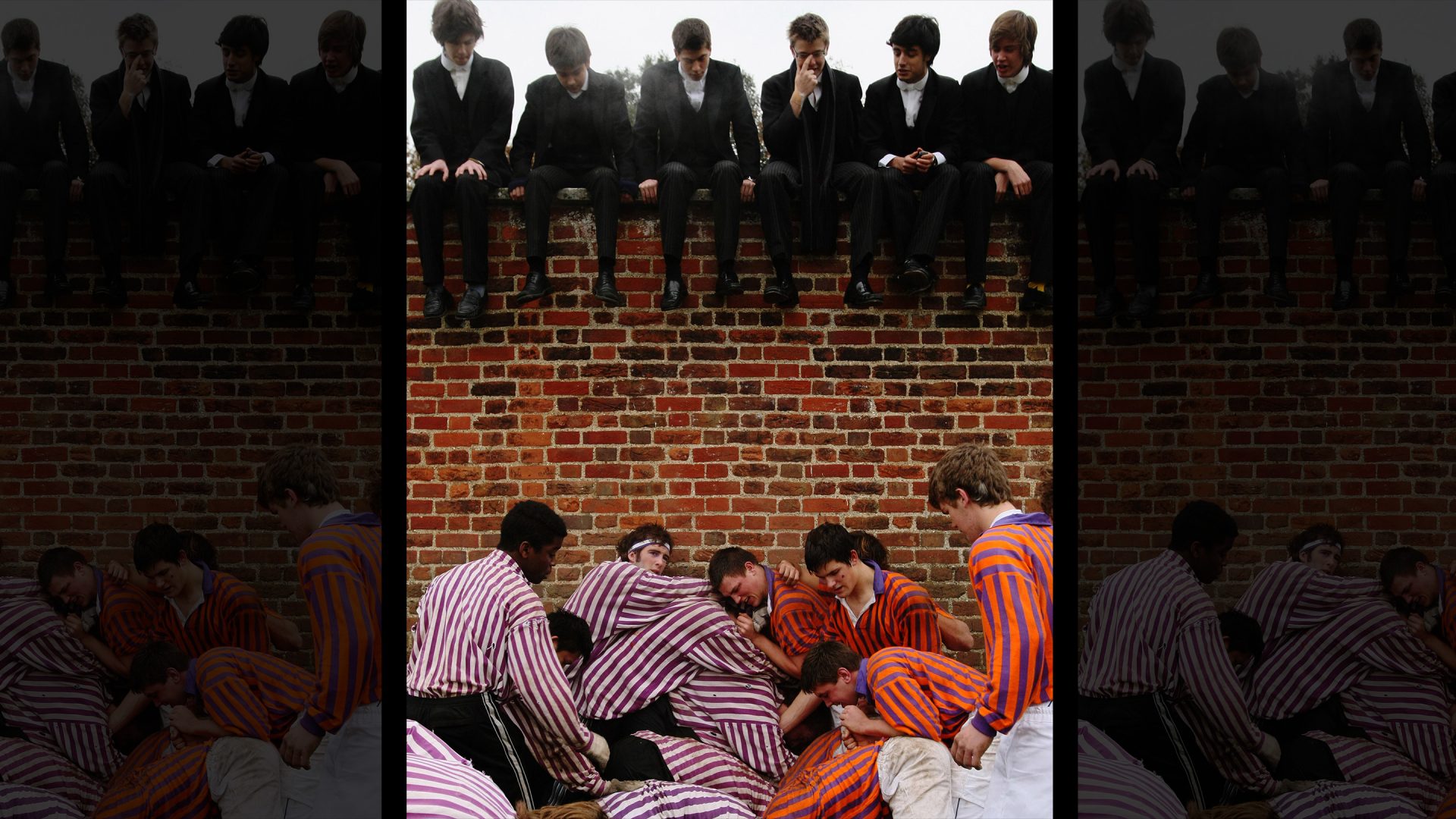

Eton College in Windsor tries its best to avoid public controversy. Though barely a day goes by without its alumni in the news, the college itself makes few public pronouncements and remains coy with curious reporters.

So, it must have been deeply discomforting when, in September 2019, Eton hit the headlines.

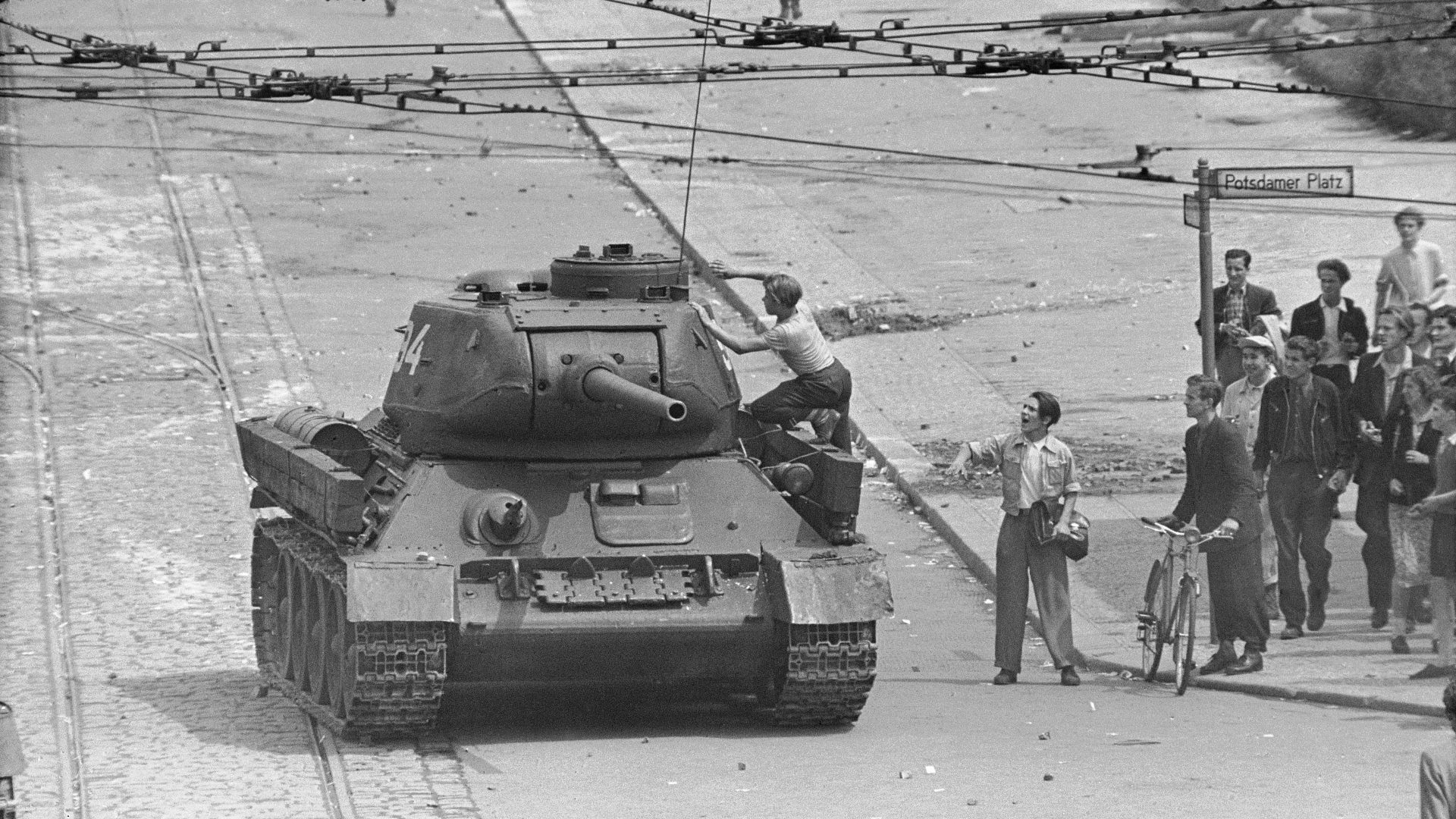

With Boris Johnson recently having been installed in 10 Downing Street, various commentators found an Eton entrance exam paper from 2011, in which prospective students were asked to draft a speech from a theoretical prime minister, justifying the killing of protesters. It’s worth recounting the exam question in full, to give you a sense of what exactly the college was asking of 12 to 13-year-old boys:

“The year is 2040. There have been riots in the streets of London after Britain has run out of petrol because of an oil crisis in the Middle East. Protesters have attacked public buildings. Several policemen have died. Consequently, the government has deployed the army to curb the protests. After two days the protests have been stopped but 25 protesters have been killed by the army. You are the prime minister. Write the script for a speech to be broadcast to the nation in which you explain why employing the army against violent protesters was the only option available to you and one which was both necessary and moral.”

This is a pretty ghastly task to give to any child, but it is made even more disturbing by the fact that 20 of the UK’s 57 prime ministers to date (more than one in three) have been educated at the boarding school. This includes two of our last five leaders, governing for nine of the past 13 years.

If these are the ideals being instilled in Old Etonians during their formative years – that they should expect to reach high office and be ready to commit and justify atrocities against their own citizens – should we be shocked by Johnson’s blasé response to mass Covid-19 fatalities, or David Cameron’s willingness to push people into food banks through his austerity agenda?

Cameron and Johnson were not one-offs, however, but rather signify a renaissance of the British aristocracy in politics and business. The meritocratic ideals seemingly embodied by former prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and John Major – the former the daughter of a grocery shop owner; the latter having left school at 16 with three O-levels (ie GCSEs) – have been wiped from the latest breed of Conservative leaders.

The march of the meritocracy has been halted, and in some respects has even been sent catapulting into reverse, with the Conservative Party once again in the thrall of a rejuvenated aristocracy.

While Thatcher, Major and Tony Blair tried to squeeze out this old money elite, it has morphed and returned in a new guise. As Iain Overton wrote for Byline Times in August 2021: “Eton College appears to have become almost pestilent in British public life. Today, almost every single pillar of British society boasts, at its head, an old Etonian… “These include the [now former] Leader of the House of Commons and Lord President of the Council, Jacob Rees-Mogg; the [former] Chief of the General Staff, General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith; the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby; the [former] editor of Britain’s most influential paper – the Daily Mail, Geordie Greig; and a Justice of the Supreme Court, Lord Leggatt – while in 2020 another old Etonian Justice, Lord Robert Carnwath, retired… not to mention our king-in-waiting, Prince William and his brother, Prince Harry, who both attended the school.”

As Mark Carnegie, the Australian scion and Johnson’s main opponent for his second run at the Oxford Union presidency, remarked to Sonia Purnell for her book Just Boris: “It became clear to me how powerful Eton is as a manufacturer of cultural capital. It’s disproportionately powerful, devastatingly so.”

The cultural power of Old Etonians can be traced in no small part to our innate national deference towards our alleged social superiors. Britain still fawns over monarchy, the aristocracy, and the trappings of privilege. We take a weekend stroll around their properties and watch TV dramas about their gilded lives.

Despite the language of “meritocracy” that has pervaded modern politics, there has been the enduring sycophancy towards the likes of Johnson and his brand of idle genius. A working-class politician, for example, would not get away with the tangled hair, baggy suit and slurred speech that has come to form Johnson’s wildly successful political brand. It could even be argued that a sense of entitled self-assurance is essential to the modern politician.

Aside from delivering good grades, private schools are valuable because they educate students about systems – the ways to navigate the modern world to enhance your power and wealth. Graduates are also endowed with the social manners of the elite – allowing them to assimilate easily into high society (if they were not otherwise born into it). British institutions of this nature are different to many of those in the rest of their world because of their histories; their sense of superiority spans back generations, with that weight of history loaded on to the egos of the most self-regarding students. Nick Clegg, Nigel Farage, Blair, Cameron and Johnson were all privately educated, all (aside from Farage) attended Oxbridge, and all were (and still are) absolutely certain of their own convictions.

Former prime minister Theresa May was also privately schooled, but she corresponds more with former prime minister Gordon Brown and Labour leader Keir Starmer – all of whom are politicians less comfortable in the limelight. There’s an awkwardness to them, an uncertainty – if only in public – created by the absence of pestilent privilege.

Johnson shares an alma mater with former prime minister Harold Macmillan, the Old Etonian who served as prime minister from 1957 to 1963, but there is a key difference between the pair. Macmillan fought in the first world war and was badly injured as an infantry officer, something that you can’t imagine of Johnson, who combines the blithe incompetence of Blackadder’s Melchett with the vanity of Lord Flashheart.

Part of the reason that Johnson was able to persuasively express his “make Britain great again” philosophy was because he embodied the past: he was and still is the Bertie Wooster of Westminster – Bertie being the affable English gentleman created by early 20th-century author PG Wodehouse – merely stripped of Bertie’s bashful naivety. Johnson and his political acolytes embody old aristocratic privilege, yet alongside an abandonment of old aristocratic ideals of public service. Infamously, however, even aristocrats of Macmillan’s era didn’t always enact the most publicly spirited policies, despite their public services virtues – a contradiction that can be traced back to the private-school system. The oldest and most socially exclusive private schools in particular bred individuals for imperial management – a form of national service that involved the exploitation of vast numbers of people.

The nature of British capitalism, and the private school system, was historically designed to “extract wealth from the countries within the British Empire, which has now been enshrined in corporate law and how the neo-liberal economic system functions,” Labour MP Clive Lewis has suggested. However, now that Britain has lost its empire, “these same laws and principles have been used to extract wealth domestically”.

This imperial mindset is sustained at the University of Oxford, writes Simon Kuper in his book Chums, which says that the history and architecture of the university produces an obsession with the past, and a misplaced assumption that the British state (and state of mind) is more powerful than it actually is.

This is why the likes of Johnson were obsessed with entering high politics; they wanted to reinvigorate the age of empire, with them ruling the world. This is epitomised by Britannia Unchained – the libertarian manifesto for Britain, authored in 2012 by Liz Truss, Kwasi Kwarteng, former home secretary Priti Patel, ex-foreign secretary Dominic Raab, and the Conservative MP Chris Skidmore.

It states that: “Britain has lost confidence in itself, and what it stands for. Britain once ruled the Empire on which the sun never set. Now it can barely keep England and Scotland together… To avoid decline, Britain needs to look out to [sic] rest of the world and learn once again what it seems to have forgotten.”

The industrial-imperial era was the nation’s high point, this reading of history contends, when Britain led the international rat race. However, in modern Britain, hard work and innovation are being stifled by the warm embrace of the welfare state and regulation, the authors suggest. As the book’s most infamous quote states: “Once they enter the workplace, the British are among the worst idlers in the world. We work among the lowest hours, we retire early and our productivity is poor.”

They consequently suggest that insecurity is a necessary bedfellow of economic dynamism. At one juncture – pushing this ethos to its most extreme – Britannia Unchained suggests that Brazil’s favelas are an example of an environment in which entrepreneurship can thrive. “As a sheer experiment in what the poorest entrepreneur can achieve, when nearly all society’s strictures are relaxed, the informal economy is pretty hard to beat,” it says. In this perverse cosmology, our “beating” of other countries in the era of empire is more important than the material gains experienced by the majority of people during the post-imperial evolution of the welfare state and the institution of workers’ rights. Or, to put it another way, things were better in Britain before the creation of the modern welfare state. Britannia Unchained is therefore a reflection of the country that its authors would like to govern – a neo-imperial power.

Yet, the challenge for the aristocracy – in an open, supposedly meritocratic Britain – has been in persuading the public that it deserves to rule a neo-imperial power. In his 2012 Conservative Party conference speech, Britain’s Eton- and Oxford-educated former prime minister Cameron remarked: “It’s not where you’ve come from that counts, it’s where you’re going.” This notion of meritocracy hasn’t really changed since 1958, when it was first theorised by political scientist Michael Young (the lefty father of Toby) in his seminal dystopian text, The Rise of Meritocracy. Young suggested that meritocracy is based on a simple algorithm: IQ + effort = merit.

In other words: to achieve what you want to in life, all you need is hard work and talent. As the authors of Britannia Unchained suggest, the only thing holding back the working class is a lack of graft. Those at the top of the pile are simply superior and are thus deserving of their power and riches.

There is, however, plenty of evidence that educational performance relies heavily on social background. The 2018 Access to Advantage report conducted by the education charity the Sutton Trust, which examines social mobility in Britain, noted that, over a three-year period, eight of the UK’s top schools received as many Oxbridge acceptances as 2,894 schools and colleges combined, three-quarters of the total number of applicable institutions.

The Sutton Trust also highlighted how independent school students are seven times more likely to get places at Oxbridge than students from non-selective state schools, and more than twice as likely to go to a Russell Group university. Likewise, you are approximately half as likely to go to Oxbridge if you’re an applicant from the north or the Midlands, compared to if you’re an applicant from the south.

There has been a social algorithm that has sorted children for centuries – it just wasn’t created by a computer. And so, for all the rhetoric of social progress that has emanated from the Conservative Party, the idea of meritocracy has counterintuitively sustained the quiet and continued preservation of a hereditary elite in business and in politics. Indeed, some 70% of Liz Truss’s first (brief) cabinet was educated at fee-paying schools. This included the chancellor, foreign secretary, home secretary, deputy prime minister (who also served as health secretary), defence secretary, justice secretary, business secretary, education secretary, levelling up secretary, and transport secretary.

Each holder of a great office of state (aside from Truss herself), was privately educated. This compares to just 7% of the population overall who are educated privately and 29% of MPs elected in 2019. In fact, ever since the Conservatives gained a clear House of Commons majority in 2015, the holders of high office have been drawn from increasingly elite school backgrounds. Around 50% of Cameron’s 2015 cabinet were privately educated, falling to 30% among May’s 2016 cabinet, before soaring to 64% under Johnson in 2019 to 2020 and then 70% under Liz Truss. It stands at 61% among prime minister Rishi Sunak’s first administration.

This has wider significance, beyond the hypocrisy of the meritocracy and the inability of working-class people to reach the highest political offices. Namely: a politician’s background informs their view of society and economics, and therefore their decisions. The disproportionate clustering of the privileged in positions of power typically creates a disconnect, some would say a disregard, for the circumstances of the poorest – who are dismissed as feckless and anti-aspirational.

This has been the rhythm of the Conservative Party’s rhetoric throughout its recent history. “To look at everything through the lens of redistribution, I believe, is wrong,” Truss has said. “Because what I’m about is growing the economy. And growing the economy benefits everybody.” Truss has similarly claimed that lower economic output outside London is “partly a mindset or attitude thing” – a libertarian conviction widely used to justify restricting state support for the poorest people.

This mindset, which pervades our collective understanding of “meritocracy”, has justified successive governments pilfering the lunch money of the poorest and giving it to the rich. Indeed, the very private schools that have educated generations of Conservative cabinet ministers – including those currently governing the country – benefit from tax exemptions to the tune of £3bn every year, according to academic estimates.

Ergo, the UK’s 1,300 private schools gain tax advantages equating to more than 6% of England’s total state school budget. Moreover, the profits and capital gains (profits on the sales of investments including shares, land and facilities) of private schools are exempt from income tax, capital gains tax and corporation tax. Meanwhile, in England and Wales, private schools receive an 80% discount on business rates and can claim an extra 25% from the government on all donations received. These tax exemptions were created in the early 20th century and have not been amended since. In return, private schools must fulfil a charitable purpose, providing a public benefit with their resources – mainly in the form of fee remissions to relatively poorer students.

However, the rules applied to these remissions are vague. A court case in 2011 set the basis for the charitable support required by independent schools – stating that they must provide remissions to those of “modest means” – defined as those who could not afford the school’s full fees. Given the drastic inflation in private schools’ fees in recent decades – more than doubling in the last 25 years – these institutions are now able to deliver on their charitable requirements by offering financial assistance to relatively well-off pupils.

In the 2018-2019 academic year, UK private schools awarded fee remissions totalling more than £1bn to 176,234 out of their 537,315 students. Of this £1bn, some £440m was means tested. The means-tested £440m was shared between 44,395 students – an average of around £1,000 per head. Just 6,118 – 1.1% of all private school students – received a full scholarship, and a further 2.1% received fee remissions in excess of 75% of fees.

It costs £43,335 a year to attend Winchester, a boarding school that before September 2022 only accepted boys. Meanwhile, Eton charges £44,000 a year for attendance – comfortably more than the average full-time salary in the UK, which stood at £38,000 in 2021. The published financial accounts of Eton and Winchester College show that they possess total reserves of £323,000 and £526,000 per pupil respectively.

Private schools are “subject to little or no accountability with regards to the effectiveness or equity with which they use this cash,” according to the academic research mentioned earlier. Indeed, many of these institutions invest in new luxury facilities, which further inflate school fees. Eton’s science department, for example, was given a £20m makeover in 2019, while the construction of an aquatics centre – boasting a 25-metre pool with a movable floor – has recently been completed. St Paul’s all-boys school, with annual fees at £40,000, likewise recently polished off a 10-year building project, costing £114m.

This all signals a wider trend: “elite” institutions, with few formal regulations governing their conduct, serve an increasingly narrow, international upper class that has seen its wealth and influence swell in recent years. Meanwhile, persistent economic and political crises are suffered by the rest of the population. As the institutions of democracy, academic learning and wealth creation are increasingly captured by this elite, the country appears to be betraying its commitment – however distant – to meritocracy. Instead, it appears that we are moving closer to plutocracy – a ruling class whose power is derived from its wealth.

At Eton in the 1990s, as one of its only black pupils, Musa Okwonga, writes in his Eton memoir, One of Them, “I look at the school’s motto, ‘May Eton Flourish’ [Floreat Etona], and I think, it is not right that you flourish, and will continue to flourish, at the expense of so many others.”

Bullingdon Club Britain by Sam Bright is published by Byline Books.