One of the myriad ways I paid for my university education back in the 1970s was by working late nights at a blues club in Chicago called Wise Fools. Every major rock and blues musician, when in the city, stopped by to play after hours, so you never knew who would be there at the bar ordering a drink.

I kept my head down, being an African American girl, because back in those days you were fair game in a place like Wise Fools. And the Chicago Police Department’s motto, “We Serve And Protect”, did not extend to you.

I was chased all over the place by various drunken types as I tried to balance a tray of drinks, plus collect money and hopefully tips. Because if a customer got away without paying, the server had to pay and that was certainly not the point of being there, as colourful as it all was.

One evening, a tall African American woman ambled in, carrying a guitar and dressed in overalls and a shirt. On her feet were big, workmen’s shoes.

My parents, both descended from not-well-off people and born in the south, worked hard to give us as genteel an existence as they could. So I knew nothing about the garb that this formidable woman was wearing, not first-hand at any rate.

But I did know. Because this was the tail-end of the civil rights movement and this woman was of that movement. Of its history and of its place. She had been born in 1926, the year before my mother’s birth, and they were both named Willie Mae, which must have been a big name in the south then and meant something. But my diminutive mom was not nicknamed Big Mama. My mother was also not the first to sing a song that Elvis Presley later made a hit.

But Big Mama Thornton had.

Everyone in the club that night had come to see this legend, but I, ensconced in a world between Marvin Gaye and Led Zeppelin, John Coltrane and Miles Davis, had simply never heard of her.

She climbed onstage, and the room went silent as she tuned up her guitar and drawled into the mic: “Ah was the first person to record Hound Dog. This is what it’s supposed to sound like.”

And where Elvis’s immortal rendition was the equivalent of a musical version of St Vitus Dance, Big Mama’s was the exact opposite: slow, deliberate; lethal. You just knew that whoever those words were directed at could be dead at the end of the song. Dispatched by a full barrel in the face.

To be called a Hound Dog implied being a guy who was just a dog, and this was, in Big Mama’s world: simply not acceptable. Her story rather sealed my suspicions of Elvis Presley, suspicions I had had ever since I saw him on TV as a kid and wondered exactly who and what he was.

My dad, born in Mississippi like Elvis had been; and my mom, raised in Tennessee like Elvis had been, would just look at each other when he was on with that look of: “Check this mess”.

Wikipedia defines Elvis as a “singularly potent mix of influences across colour lines during a transformative era in race relations”. When I read that, I remembered a TV programme from long ago, with Little Richard at his piano and Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley leaning over it. These three greats were talking among themselves about how their riffs and lyrics had been used by other people – white people – who then Made The Money. They were laughing about it in a sarcastic way and I guess that they had to laugh. To keep from doing anything else.

There’s a Hollywood movie about Elvis in cinemas right now. We’re still waiting for one about Big Mama Thornton.

But Elvis did try to be with the times, tried to address all of us in the streets during the height of the civil rights era, which became Black Power; us with our afros and our attitudes. Yes, Elvis did try to connect.

He recorded In The Ghetto:

“As the snow flies

On a cold and grey

Chicago mornin’

A poor little baby child is born

In the ghetto (In the ghetto)

And his mama cries

’Cause if there’s one thing that she don’t need

It’s another hungry mouth to feed

In the ghetto

(In the ghetto)”

What my generation really did not need was that song, and also the fact that Elvis was for Nixon.

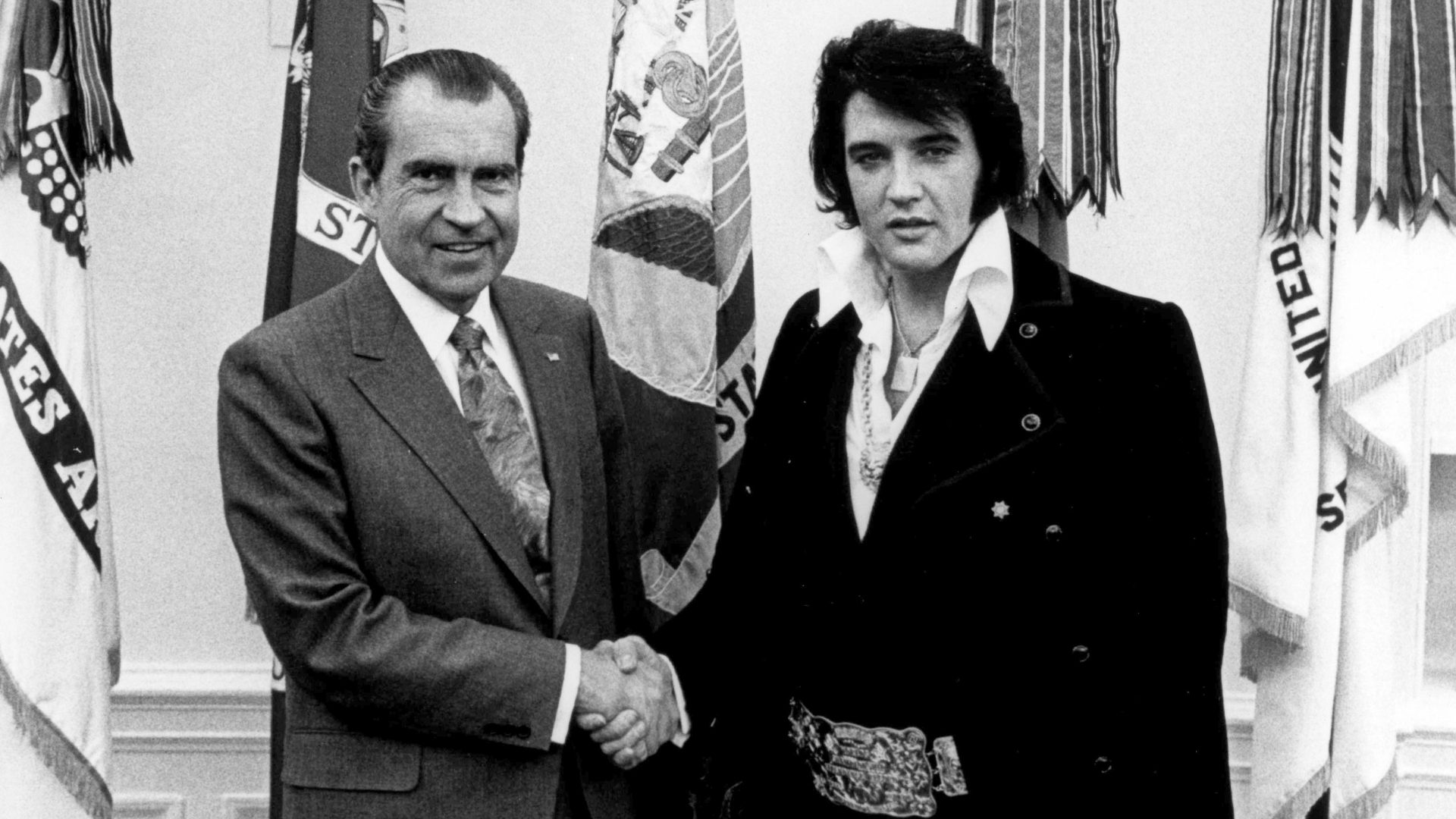

A few days before Christmas 1970, Elvis met the lying, cheating 37th POTUS, and expressed his patriotism. Elvis said that he wanted to reach out to hippies in order to fight the drug culture, maybe even inform on them. Tricky Dick was freaked out.

Elvis then asked for a Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs badge to seal the deal. He called the Beatles “anti-American”, even though he performed their songs and had hung out with them a few years before. Told about this years later, Paul McCartney would marvel at the rather ironic fate of the man with the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs badge.

So In The Ghetto was a bust for us, and Elvis with Nixon was even worse. But an odd thing happened to my largely black anti-Elvis brigade.

The thing that happened was his song Burning Love. Its passion and drive worked for us when it was released in 1972.

Here was Elvis, suddenly as exciting as he must have sounded in 1956, dressed in spangles and glitter, with a stellar backing band and a superb all-black girl quarter of backing singers.

“You light my morning sky

With burning love

With burning love

Ah, ah, burning love

I’m just a hunk, a hunk of burning love”

For that brief time, in that song and in the way he did it and the realness of it, I and my friends understood what he was doing, understood maybe why he was great, too.

There was something trying to get out of Elvis, something trying to get free. That lyric and the way he sang it made us, not his biggest fans, finally get him and the point of him.

When they found him dead five years later, on August 16, 1977, I had to stop a minute. The world had changed and even I had to admit it. Star Wars had premiered a few months earlier and a lot of people were still full of that. But Elvis was gone.

So was he The King? Not to me. But he was The King to millions and that has to be respected.

They gave him “burning love”. He gave it back, and I’m very glad that I had grown up enough to see that.