“All those prawn cocktails for nothing,” Michael Heseltine once taunted Labour leader John Smith in the Commons. That was in 1994, when Labour was on its long march through the City of London, trying to persuade business leaders it could be trusted with government after 15 years in the wilderness.

“Never have so many crustaceans died in vain,” Heseltine quipped. But by 1997 the Tories were not laughing. Under Smith’s successors, Blair and Brown, Labour’s “prawn cocktail offensive” had made the business case for a social-democratic government – and its reward was a landslide.

Today Keir Starmer is reported to be engaged in the same travails – lunching and dining with big consultancies, banks and tech monopolies. But it’s a totally different world.

The prawn cocktails are replaced with microscopic Asian canapés served on slates. The executives on the other side of the table are drawn from a global talent pool. And the roll-call of companies ejected from the FTSE since the days of Heseltine reads like a casualty list for British capitalism.

Today’s FTSE 100 is heavy with global mining companies, oil and gas majors and international banks: it barely correlates with the operational reality of domestic capital at all. And as the fiasco we have just lived through shows, the only businessman that really matters is Mr Bond Market, who does not attend receptions and has no business card.

So what should Labour’s offer to business be? Even under Jeremy Corbyn there was an understanding that it had to have one.

In 2017, together with shadow chancellor John McDonnell, I dined with City fund managers eager to have their say about his tax and spend programme. “Borrow as much as you want,” was the consensus, “but just don’t tax the wealth of any blue-blooded Tory hedge funders or they will bring you down”.

Today, I suspect, with inflation eroding the value of Britain’s debt, gilt yields above 4% and the fundamentals of the economy much weaker, the same people might be less generous on the borrowing side, and equally sanguine on the bringing down.

What global corporations want, when making big investment decisions, is a clear long-term growth model, giving certainty about the kind of regulations they can expect – and the instinctive reaction of government to surprises – over a period of 20 years.

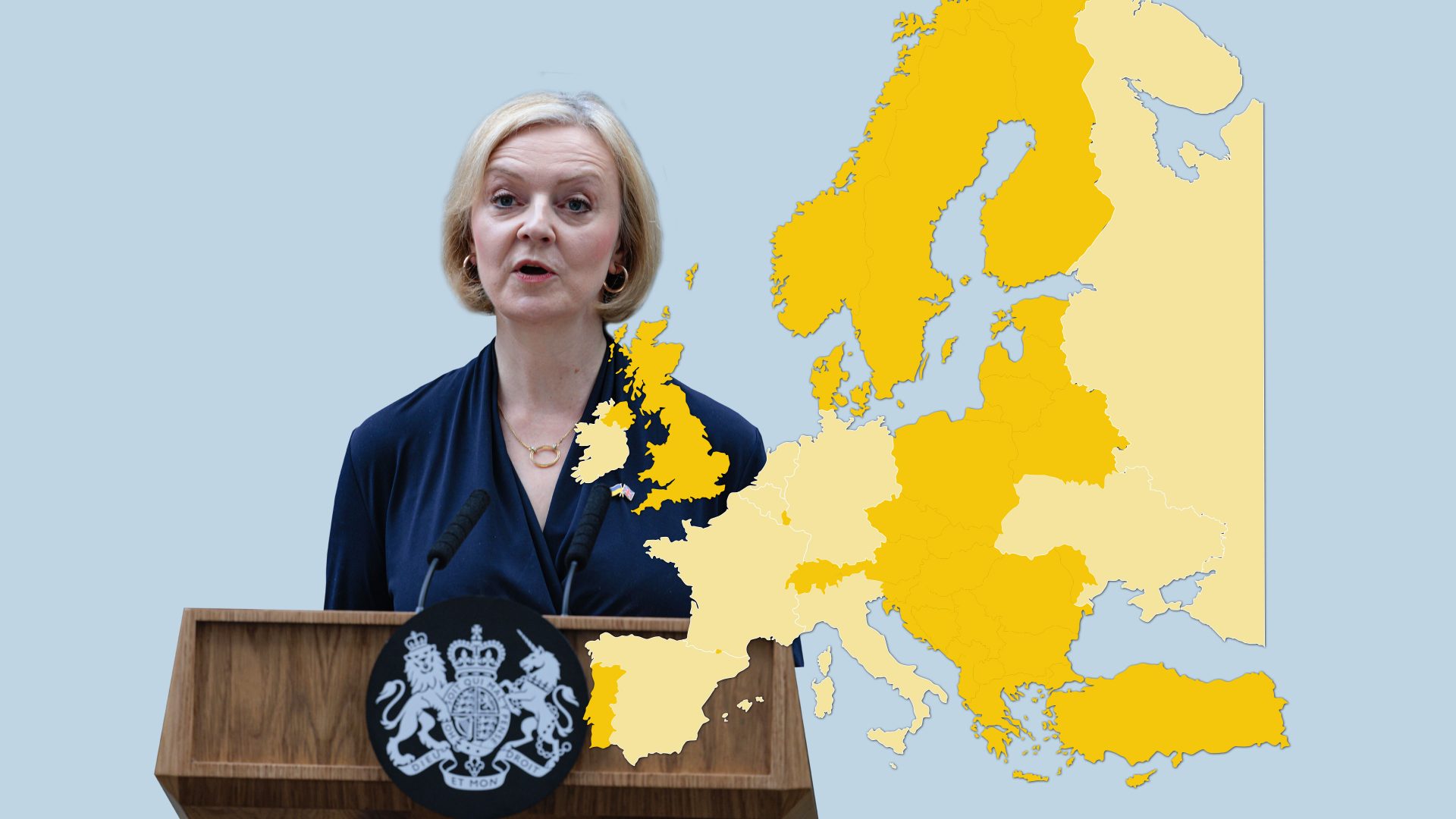

The bond markets imploded on the Tories because, since duping the country into hard Brexit, they haven’t provided one. Investment has flatlined since 2016. The trade density of the economy has fallen. And sterling had lost nearly a third of its value against the dollar even before the turbulence unleashed on September 23.

Labour, by contrast, has a clear intent. Rachel Reeves’ central proposal is a £28bn a year investment programme in green energy, transport, smart manufacturing and skills. Shadow business secretary Jonathan Reynolds has purloined the methodology of Mariana Mazzucato’s research unit at UCL to build the outlines of a “mission oriented” industrial strategy. Transport chief Lou Haigh’s announcement that Labour will take the railways back into public ownership signals a pragmatic direction of travel.

It’s possible to see in the mind’s eye what would happen if things went right under Labour.

It would first calm the markets by issuing clear fiscal rules and demonstrating competence. Its principles are: borrow only to invest and raise money for extra public spending through the tax system. Rachel Reeves would have to demonstrate what Kwarteng could not with his tax cuts: that a mixture of borrowing, tax rises, investment and public spending could produce a multiplier effect on growth.

And that’s where Labour’s conversations with business leaders matter. Because once there’s regulatory certainty there also has to be detail.

Right now, Munich-based automaker BMW is said to be mulling the relocation of production of its electric Minis from Oxford to China. The firm has remained uncommunicative as to the reasons, and can hopefully be dissuaded. But the glacial pace of roll-out of the EV infrastructure in the UK – high-speed charging points on roads and homes – plus the slow build-up of battery gigafactories has to be an influence.

Convincing BMW to keep EV production in Oxford, convincing battery makers like the Taiwanese group ProLogium to build their European gigafactory in the UK – not France, Germany, Poland or the Netherlands – will require, according to one industry briefing: “a pool of skilled labour, an existing supply chain, energy security and government incentives”.

So, telling a coherent story only gets you into the conversation. Clinching the deal requires a “build it and they will come” mentality that we have not seen in Britain outside the finance and speculative construction sectors. Which means a state-directed industrial strategy and the institutions that can deliver it.

The Johnson government abolished its own Industrial Strategy Council. It was deemed pointless amid the Cummings-driven fantasy that Britain could become a global “science superpower” through willpower and crankery. Labour’s replacement body will have a statutory footing – but what it delivers will be dependent on the kind of micro-structures it can create at the grassroots.

Creating a “pool of skilled labour” means setting up technical colleges, training teachers to provide subjects like further maths (or importing them if you can’t), imposing training levies on reluctant sectors – and then persuading young professionals to choose careers in small, inland British cities as opposed to big, coastal ones in the USA, Canada or Australia.

To make this work we’re going to need a vast cultural change – of the kind that only happens in synchrony when led from below. And with 400,000 members, and millions in its affiliated unions, maybe that’s Labour’s strongest card.