When Auguste Rodin died in 1918, Guillame Apollinaire, French writer and chronicler of the artistic avant-garde wrote: “Medardo Rosso is now without a doubt the greatest living sculptor”. Hailed as the “founder of impressionist sculpture” and feted by later generations of sculptors including Henry Moore, Rosso remains the greatest European sculptor of the modern age that no one has ever heard of.

In a bid to correct this historical amnesia, a new show has opened at the Kunstmuseum Basel. It brings together 50 of the artist’s sculptures, with 250 of his photographs and drawings, and places them in dialogue with another 60 sculptors from the 20th and 21st centuries.

Born on a train in Turin in 1858, Rosso went to art school in Milan where he railed against the hoary traditions of academic art and was expelled for punching a fellow student. In 1889 he relocated to Paris where he became acutely attuned to the rush of modernity, and the new age of mechanical reproduction, one in which photographs, moving images, and objects mass-produced in the factory became ubiquitous.

Like the circle of Impressionist painters who were his direct peers, Rosso became interested in attempts to capture the transient flow of life, and the fleeting nature of perception. This was a radical goal for sculpture, an art form defined by stillness and claims to permanence.

Long considered turgid and old-fashioned, French writer Charles Baudelaire deemed sculpture to be “boring” in 1846. Rosso went further and rejected it as a category altogether, claiming: “There is no painting, there is no sculpture, there is only a thing that is alive.”

The exhibition is unapologetically intelligent (this is a good thing), and meanders thoughtfully across the spaces of the vast Kunstmuseum, beginning already in the museum’s imposing courtyard, where Rodin’s pathos- laden sculpture The Burghers of Calais sits next to a stone fountain bubbling with a pink pool of viscous liquid by Basel-based artist Pamela Rosenkrantz. Side by side, the two works represent the polarised extremes of what sculpture can be.

On the one hand, Rodin’s work, cast in bronze immortalises a heroic event from medieval history. On the other, Rosenkrantz’s bubbling Skin Pool lacks any narrative and is permanently in flux, couched instead in conceptual ideas about materials, and their ability to dissolve and transform. The allusion here is to the traditional world of 19th-century sculpture that Medardo Rosso emerged from, and the impact his revisions of the medium had on future generations of sculptors who embraced liquidity and movement.

The opening room sets the tone with an array of Rosso’s sculptures set on their original plinths or in small vitrines or gabbie (Italian for ‘cages’). Among them is Uomo chi legge (The reading man), cast in wax, one of the artist’s signature materials, appreciated for its malleability and suppleness.

What first appears to be a glossy piece of paleolithic bone slowly reveals the subtle delineation of a standing figure reading an open newspaper, a quotidian figure to be found in the boulevards and cafes of the Parisian metropolis, and not the idealised heroic figure that sculpture historically had depicted.

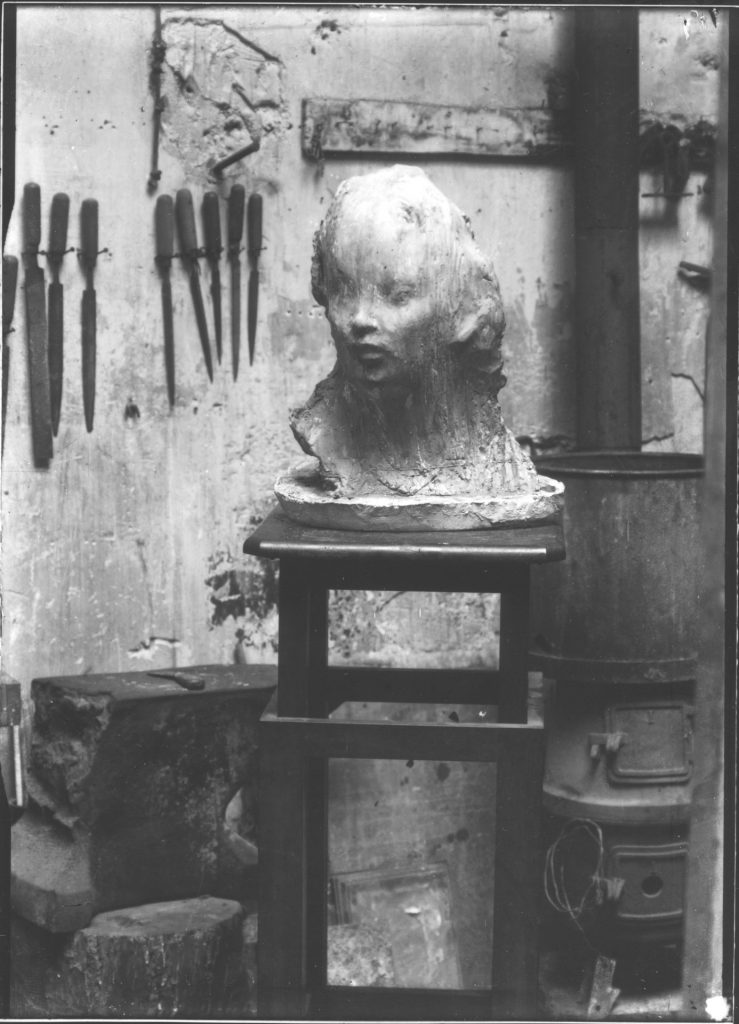

Rosso’s subject matter was found in the everyday: mothers and children, the sick, the drunk, the desperate. Recurring motifs include the forlorn Jewish boy, Sick child and the anonymous building concierge. There are examples of his experiments with the portrait bust, a form weighted with lofty traditions of grandeur.

In Rosso’s hands, Henri Rouart – a French painter, engineer and prolific art collector – appears with furrowed brow and artist’s cocked beret, a tiny head poking through a roughly formed hunk of plaster like a seedling through a clump of soil. It has, like all of Rosso’s sculptures, a feeling of the unfinished and imperfect, full of gashes, bubbles, holes from the casting process, and places in which the material has escaped the mould to create unpredictable effects. A contemporary critic even described Rosso’s works as “gaseous”, as if they were made up of unanchored particles that cohere and disperse. In another portrait of Madame Noblet, a barely perceptible face is consumed by a mass of stone, and slips in and out of recognition depending on where the light falls.

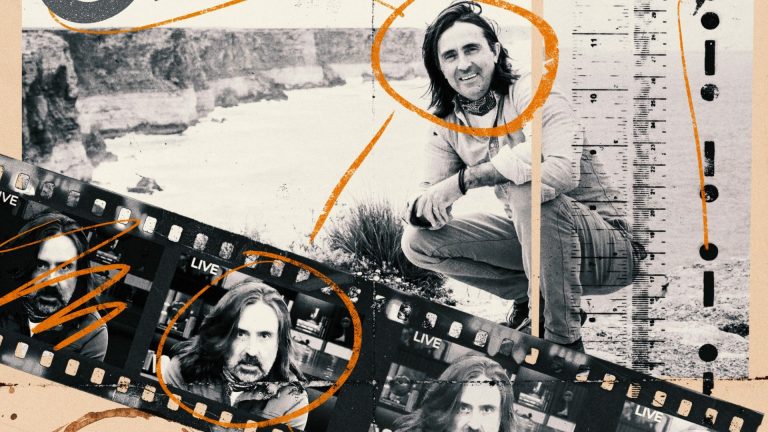

Around the edges of the room are Rosso’s experiments in photography, which made up an integral part of his artistic process. Sculptures were staged in varying settings and light conditions, then cropped and collaged together with drawings and even photographs of drawings to make new montages which would influence further adaptations to the sculpted works. As co-curator Elena Filipovic suggests, “the photograph is a tool for him in the process of making – while some artists use a chisel, Rosso uses a camera.”

Working at a time in which photography itself was still an emergent experimental medium, Rosso’s sculptures were described in 1905 by critic Ludwig Hevesi as a type of “photo-sculpture”, drawing similarities between the blurred, indistinct edges of the artist’s three dimensional sculptures and the halo effect of light on photographic paper.

The exhibition continues upstairs where Rosso’s broader legacy is considered in a sequence of rooms drawing parallels between his practice and a host of 60 other artists, a mode of display that Rosso himself cultivated in his own time, staging his work alongside peers such as Rodin and Cezanne.

Here, echoes are sought out in works as diverse as Louise Bourgeois’s stuffed and sewn soft sculptures to a gleaming bronze head by Constantin Brancusi and a Francis Bacon painting. Connections are largely forged through meditations on material and process, for example, the ‘Repetition and Variation’ theme takes Rosso’s compulsive reworking of his core motifs as a starting point to think about serial production in a new cultural climate informed by factory lines and the mechanical reproduction of objects and images.

Here, Andy Warhol’s repetitive screen print Optical Car Crash (1962) sits next to Richard Serra’s Candle Piece (1968) of identical mass -produced candles all burning with different flames and configurations of dripping wax.

The ‘Anti Monument’ room brings together works that are deliberately off-kilter, an approach Rosso himself took as a way of undermining the traditional idea of what ‘sculpture’ should be. It includes Degas’s peculiarly awkward Fallen Jockey, a painting that comments on the end of the traditional equestrian statue and portrait, one that defined a certain type of authority and status. Elsewhere, a room on the ubiquitous mother and child motif explores Freudian themes around parental touch as something that consumes as well as generates. Rosso’s sculpted study of his wife embracing their child depicts a dyad hidden in what looks like volcanic rock, and reminds me of whimsically searching for faces in clouds.

The approach is largely successful although occasionally risks overstretching the analogies, and at times verges away from engaging with the elusive Rosso, who remains a sculptor who is hard to grasp. I found myself distracted by a wonderfully creepy Eva Hesse sculpture, or documentary photographs of Alina Szapocnikow making a plaster cast of her nude, adult son, or ruminating on one of Felix Gonzalez-Torres ‘candy works’ of glistening, wrapped sweets stacked in a pile for visitors to consume and take away (a comment on the dispersal of the HIV virus that consumed Gonzalez-Torres and his partner).

Rather than focussing on Rosso’s biography, or the artistic milieu of early 20th century Paris, the curation favours a constellation of connections relating Rosso to developments in modern sculpture from his time to today. Among these threads are how sculpture has subverted convention and how it has approached the cultural themes of its time. It’s an approach that rewards a thoughtful audience with suitably heavyweight ruminations on 20th century sculpture (reflected in the hefty exhibition catalogue, which weighs in at a whopping two kilos and includes an essay by erudite French philosopher Georges Didi Huberman.)

The show marks the debut for curator and newly appointed Kunstmusuem director Elena Filipovic who co-curated the project with Heike Eipeldauer from mumok museum in Vienna, where the exhibition initially went on display. I ask Filipovic why despite the eulogies from his peers in his own time, Rosso was left behind by art history.

Her answer is Rodin. “[He] took up all the space, he understood the importance of how to make things big,” Filipovic says. Moreover, Rodin also knew how to lean into his network, calling on the professional photographer Edward Steichen to take glossy commercial photos of his work. (While Rodin was initially effusive with his admiration for Rosso, the relationship soured when Rosso accused him of pilfering his ideas.)

Filipovic is keen to emphasise Rosso’s potential to inflect meaning on the here and now. “I think we are living in an Instagram-promoted moment of product production and selfie production. You take a picture of any Rosso and it doesn’t read well in photos. It wasn’t made to be easily consumable… it’s about close looking, it doesn’t sit still and doesn’t look cosmetically beautiful, and in this moment we need the artists who stand for that to be given their place,” she says.

Despite the curator’s judgement, there are undeniable moments of searing beauty – the veiled face of child peeking through a curtain and cast in wax, bronze and plaster is a poetically delicate and tender meditation on vulnerability, reminiscent of religious sculpture.

There are also other aspects that offer pause for thought. Between 1906 and his death in 1928, Rosso stopped making new work, instead committing himself to undoing and remaking his suite of favourite motifs, rethinking and recasting them over and over, subtly adjusting and restaging them, breaking them apart to remake them.

There is something in this that kindles thoughts of sustainability in our hyper consumer-capitalist age, of satisfaction with what we have acquired and allowing things to fall apart and be remade; an argument for maintaining curiosity with what we have before us and of jumping off the endless carousel of longing for what is new.

Medardo Rosso: Inventing Modern Sculpture is at Kunstmuseum Basel until August 10