Imagine meeting yourself. Imagine what it would be like to walk into a room to find… you standing there. Not a lookalike, not some kind of hologram, the actual you, in duplicate, looking back at you, sharing all your memories, personal quirks, insecurities, lived experience, hopes, doubts, secrets and dreams.

Once the surprise had worn off a little, first impressions might be fairly superficial. Yes, your voice really is higher-pitched than it sounds in your head, you do scratch the back of your head when you’re nervous and, as you suspected, that hairstyle really doesn’t suit you.

But what about after that? How would the meeting go, especially when they think you’re the “other” one as much as you believe they are? What would you talk about?

How would your life be affected by the knowledge that there is another you out there in the world telling your best anecdotes and ringing your mum on her birthday?

That’s the issue tackled by The Anomaly, the 2020 Prix Goncourt-winning novel by Hervé le Tellier that, unusually for a work awarded its nation’s most intellectual literary prize, has sold well over a million copies in France since its publication barely 18 months ago. No Prix Goncourt winner has shifted in such numbers since L’Amant by Marguerite Duras, and that was nearly 40 years ago.

It’s easy to see why The Anomaly is so popular. The book ranges across questions of science, religion and philosophy with the page-turning pace of a thriller, all of it revolving around a captivating premise. A work high-falutin’ enough to feature in publisher Gallimard’s famously highbrow Collection Blanche, the book’s popular appeal has made it a lockdown hit in France and the subject of no fewer than 40 foreign translations and counting.

Screen adaptation can’t be far behind for that rare thing: a novel hailed by literary academics and Goodreads reviewers alike.

It’s timely, too. Written by the current president of Oulipo, the French organisation dedicated to pushing the boundaries of experimental literature, The Anomaly debates the nature of life, existence and what the point of it all might be, just when the pandemic was prompting similar questions in all of us.

The premise is an ingenious one. On March 10, 2021, Air France flight 006 from Paris emerges battered and traumatised from a violent storm over the north Atlantic and prepares to land at New York’s John F. Kennedy airport.

The pilot, David Markle, a few days from retirement, is baffled to find his standard requests for bearing and altitude guidance met first with uncertainty by air traffic controllers and then by searching questions from a procession of increasingly senior American officials who finally instruct him to land not at JFK as originally scheduled, but at a US military base in New Jersey.

Markle doesn’t know it, but AF006, the same Boeing 787 with the same pilots, cabin crew and passengers, has already battled through the same storm and landed safely at JFK. To make things even more complicated, it is not March 10 as Markle and everyone on board believes, but June 21: an identical aircraft with identical people on board has appeared in the sky out of nowhere, 106 days later.

It’s a fabulous set-up, one with ramifications for the individuals on board (both sets), as well as politicians across the globe, every religion in the world, scientists in all fields and philosophers from academic to barstool.

The flight is only described about a third of the way through the book. Before that we meet a selection of what turn out to be the passengers and crew, beginning with the terrifying Blake, a ruthlessly successful freelance international hitman who already has a second life, one in which he is also a family man running a chain of vegan restaurants.

There’s Victor, a lonely literary translator and highbrow novelist whose books don’t sell until, in an agreeable nod to self-awareness on the part of le Tellier, he writes a book called The Anomaly after the first flight.

Lucie is a successful film editor who, when she boards the flight, is going cool on a relationship with the much older, and more ardent, architect André, while Sophie is a young girl, the daughter of a soldier, who takes the flight with her mother and brother while her PTSD-suffering veteran father remains in France.

Joanna is a newly pregnant, black corporate lawyer, fighting America’s gender and racial discrimination, and Slimboy is a Nigerian rap and R’n’B artist hiding his homosexuality out of genuine fear for his life in his homeland.

It often surprises me there aren’t more novels set on passenger aircraft, as they can be microcosms of the world, a range of people brought together for a few hours in a giant tin can in the sky, the various threads of their lives combining for the duration of the flight before spreading out again into endless narrative possibilities.

Le Tellier has cast his net wide here, albeit restricted to the kind of people with the means to fly from Paris to New York, but still manages to create believable, nuanced characters despite the extensive cast list.

It is when he introduces Adrian, a professor of probability who wears a T-shirt bearing the legend “I love zero, one and Fibonacci” and his colleague Meredith, that the philosophical questions begin to arise.

The second plane and its passengers are squirrelled away in New Jersey where Adrian’s post-9/11 chickens come home to roost. Having provided some probability assistance to the US government in the wake of the 2001 attacks, he has managed to procure a healthy monthly stipend in return for

being permanently on call for an event of remarkable improbability.

With a nod to Douglas Adams’ answer to life, the universe and everything, he has even called the invocation of his services Protocol 42. He never expects to get the call. Then it comes.

Once a global Zoom with leaders of the major world religions has produced a surprising consensus that the duplicate aircraft is not something to be condemned on religious or ethical grounds – which doesn’t stop crackpot American Christians hyperventilating and lunging for the gun cabinet – Adrian and Meredith assemble some of the world’s finest minds in an attempt to explain what’s going on.

As Meredith says, the toss of a coin has three possible outcomes, heads, tails and landing on its side. Here they’re dealing with the equivalent of the coin staying in the air and the group has to entertain the possibility that the world and everyone on it is part of a huge computer program and the second plane is some kind of glitch, or maybe a deliberate ploy by the programmers.

“Is the fact that I don’t even like coffee written into my program?” asks Meredith. “Am I programmed to be angry when I realise I’m a program?”

The final section of the novel brings some of the characters together with their doppelgängers. The conditions are heavily supervised with psychologists present, and rigorous preparations have been made, but some meetings go better than others.

Some characters’ lives have changed profoundly in the intervening 106 days, there is serious illness, relationship changes, and it is clear le Tellier is enjoying exploring the different directions lives can take in a relatively short time.

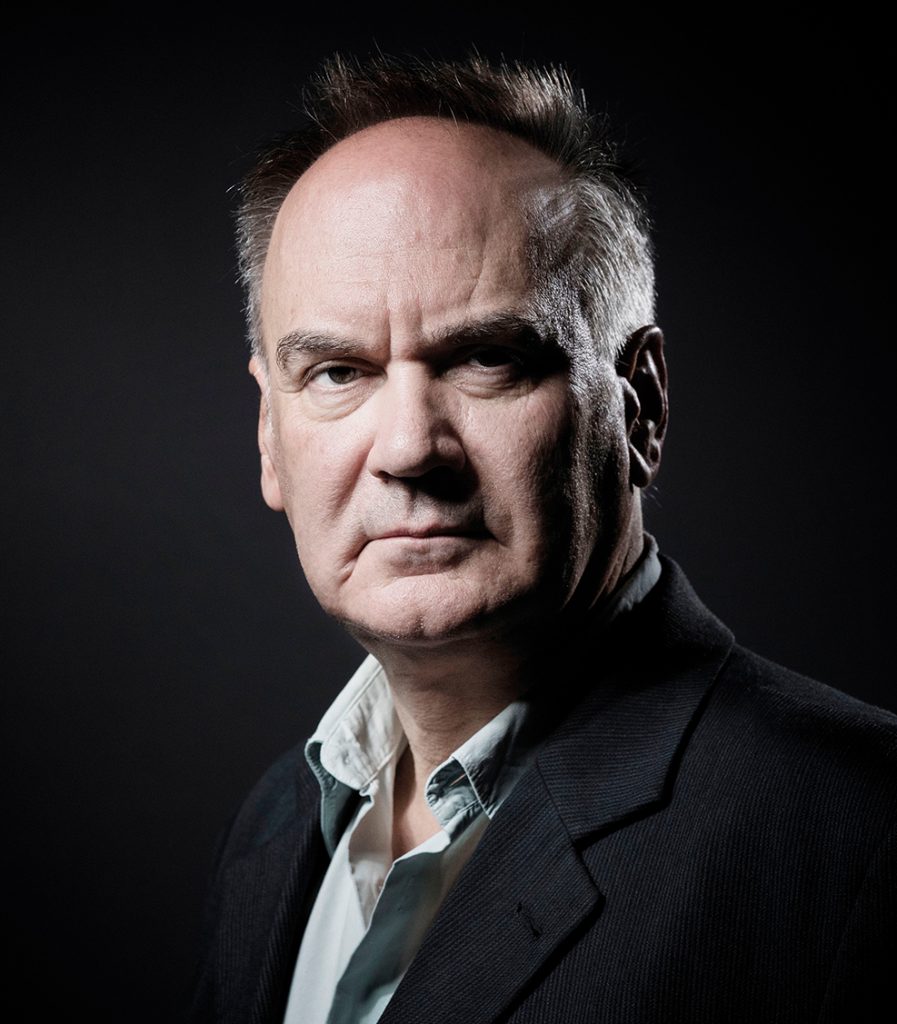

Like Oscar Wilde and Fyodor Dostoevsky before him, le Tellier is fascinated by the literary possibilities presented by a double, and has been ever since a man once stopped him in the street and said, “We know each other. I know you because I saw you in the mirror 20 years ago”. As a science writer and former mathematics teacher, he is well-equipped to tackle the subject matter with all its potential consequences on both micro and macro levels.

Misfires are rare, despite the vast roster of characters and their extraordinary situations.

A scene in which a pair of the same person appear on Stephen Colbert’s US TV show falls a little flat because what would have been quips scripted meticulously by a room full of writers have instead been created and written in French and translated into English.

This is no fault of the translator, Adriana Hunter, who has produced a brilliantly pacy and dynamic book, but le Tellier might have been better served going with a fictional host here.

But that’s a minor quibble in a book that hits its mark just about everywhere else.

The Anomaly is smart, funny, heartbreaking and occasionally wincingly on the nose with its satire.

When an Instagram influencer addresses the issue and goes viral, le Tellier writes, “Their message is obscure but freedom of thought on the internet is all the more complete now that people have stopped thinking”.

Most of all, The Anomaly is an effective and brilliant way of making us think about the very nature of existence and our place in the world.

“When seven billion human beings find out that they may not really exist,” he writes, “it’s not easy to comprehend.” I’ll be sure to remind myself of that next time I bump into myself.

The Anomaly by Hervé le Tellier, translated by Adriana Hunter, is published by Michael Joseph, price £14.99