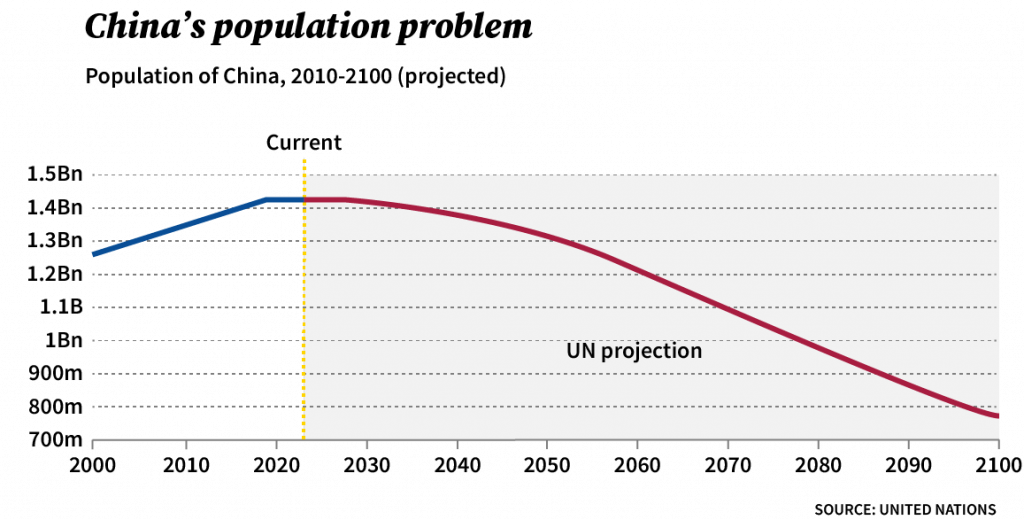

For decades it was one of China’s great advantages. Its huge population could be moved off the land and into the factories and building sites of the cities, and that army of labour built decades of prosperity. This week, the Chinese government conceded that its population is expected to decline, meaning China will shortly be overtaken by India as the world’s most populous nation. It is the latest development in the Chinese Communist Party’s doomed attempt to shape the country by using population control.

Between 2021 and 2022, China’s population fell by 850,000. The birth rate has also dropped to 7.5 births per 1,000 people, compared with a rate of 10 in the UK and over 16 in India. And while the population on the subcontinent is surging, in 2022, China recorded more deaths than births.

For Beijing, a declining population poses a profound economic and political challenge. An economy of China’s size needs a workforce to match. But if there aren’t enough young, able people to drive economic growth and to support China’s ageing population, then there is trouble ahead for Beijing, the region and the global economy.

Mao Zedong always understood that China’s large population was a strategic advantage, even if his ideas did not always bode well for them: during the long Sino-Soviet split, for example, Mao confidently asserted that China would win a nuclear war with the USSR because China could afford to lose 100 million people.

The China that Mao dominated was a largely rural economy; muscle power was one of its few assets, and long hours of labour were the norm. State-owned factories and People’s Communes ran nurseries that generally looked after children for six days a week, allowing mothers to work long shifts. Despite a devastating famine in the early 1960s – caused by Mao’s policies – China’s population grew, and by 1968 the birth rate was an impressive 6.18 per woman.

It was only after the Great Helmsman’s death in 1976 that the Communist Party began to look at the demographics again. By 1979, when China’s population had reached 969 million, they began to panic. If all those young Chinese were to reproduce at the same rate, they reasoned, China would not be able to cope. The response was brutal and uncompromising: a limit of one child per couple was imposed, sold as a modernising idea that would save China from further famine, which the party had blamed on population pressure and natural disaster. Those severe birth restrictions lasted nearly four decades. Now the population is contracting, and the party is panicking again.

The first signs of change began in October 2015 when, after decades of heavy fines, forced abortions and compulsory sterilisation, the party announced that families would no longer be limited to one child. There had always been exceptions: rich people could simply pay the fines; parents who were themselves only children could try again if they had a daughter. Families desperate for a male child simply gave unwanted daughters away. Many were adopted overseas.

Unknown numbers of births were never registered, and selective abortion became so widespread that the sex-at-birth ratio went from 106 boys for every 100 girls (as it is in most of the world) to 120, and even, in some provinces, to 130. China now suffers from a gender imbalance of nearly 30 million missing women, which translates in social terms into 30 million men who will find it difficult to marry and 30 million fewer potential mothers.

It is hard to overstate the depth of the changes in Chinese society that four decades of economic reform, industrialisation and urbanisation have brought. In a rural society, people wanted sons to work on the land. Daughters married out and became part of a husband’s household, but sons stayed around and their wives took care of their husband’s parents in old age. Extended families provided security and could often be counted on to take care of the weaker members, and to scrape together capital when the opportunity arose.

The importance of these family relationships is embedded in the language: the word for “good” in Chinese is composed of the symbol for a woman with a male child. Nuances of hierarchy in family relationships are also indicated in the language, with different words for cousins of different generations, younger and older siblings, maternal and paternal relatives. But in the decades since 1979, all those terms have become redundant. Like their parents, most of today’s young Chinese adults have no siblings, no cousins, and no aunts or uncles. The party claims that the One Child policy prevented 400m extra births – and on occasion has offered it as an example of China’s contribution to climate mitigation. But the impacts go far beyond the cultural. The long shadow of this brutal policy may undermine China’s 21st-century dreams of wealth and power.

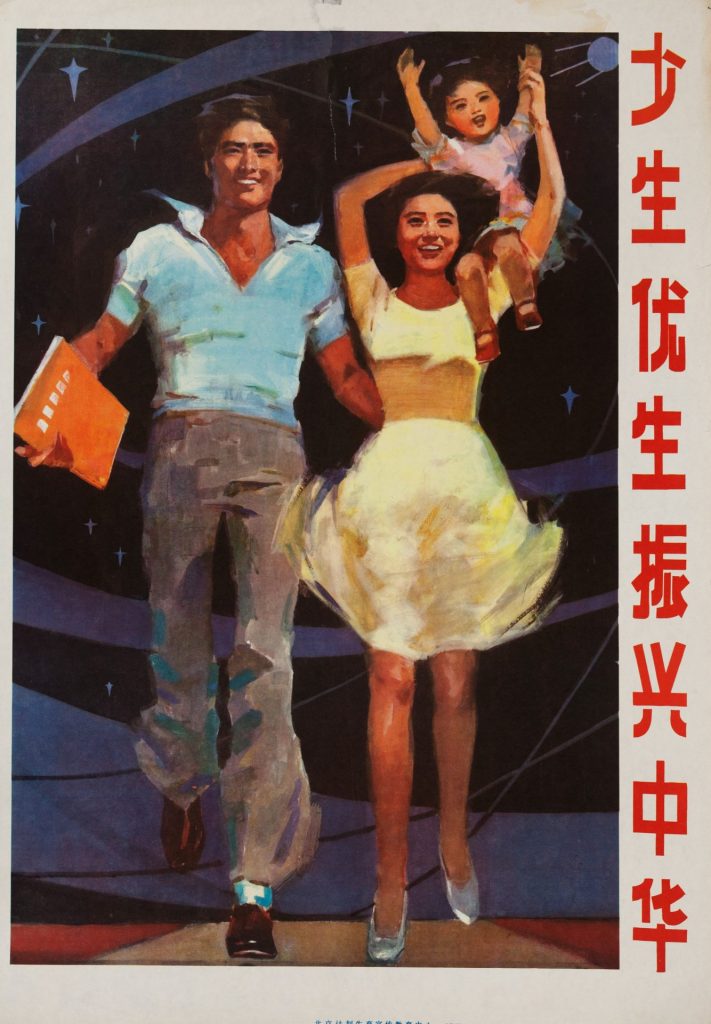

The 2015 end of the One Child policy was greeted with relief, but, to the surprise of the authorities, not much action. When permission to have two children turned into active encouragement, with promises of tax breaks for the expenses of children under three and 1,000 yuan a month tax relief on childcare, the same local family planning bureaus that had forcibly ended pregnancies for nearly four decades began to promote larger families. Neither propaganda nor persuasion had a sustained effect. A brief baby blip quickly expired and since then the numbers have continued to decline. In 2019, four years after the announcement, the birth rate was 10.5 per thousand people, the lowest it had been since the founding of the People’s Republic 70 years earlier. Now that the birth rate has sunk to a new, record low, China’s child-bearing generations are coming under increasing pressure as the party continues its effort to shift the attitudes of China’s youth towards pro-natalism.

In June 2020, in a continuing effort to persuade, the government made divorce harder and, at the same time, announced that remarried people could have further children. Among China’s ethnic minorities, who had previously enjoyed greater reproductive freedoms, repressive policies in areas such as Xinjiang have caused birth rates to crash, even as official family planning rules have been relaxed. In a culture that remains male-dominated there has been, perhaps predictably, more stigmatisation of women who have not married by 25, and to hammer home the message that earlier marriage might mean more babies, there are calls to reduce the legal age for women to marry from 20 to 18. Women who are still single by 30 risk being called “left-over women”, and China’s soap operas depict them as desperate and lonely. Yet in another record, just 7.6 million marriages were registered in 2021 – the lowest since records began in 1986.

Permission to have two children became permission to have three after a decision by the Politburo in May last year. And since the new draft law abolished all penalties, families were free to have as many children as they wanted. The May announcement was certainly widely read: the official news agency story about the changes had 2.2bn views by the end of the day. But absent further measures of coercion or persuasion, China’s population – now predicted to peak this year — seems unlikely to trend upwards.

A glance at China’s neighbours shows the scale of the challenge the party has created. Without any coercive intervention by their governments, the birth rates in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan have also dropped, the result of development, urbanisation and female empowerment. This indicates that China’s birth rate would have declined anyway, but has been pushed even lower by government meddling. Today, China’s young people are also overwhelmingly urban. They live in small apartments and work for companies that offer little maternity leave or parental support. In addition to the costs of childcare and education, couples in this generation must face the added responsibility of potential old-age care for up to eight grandparents.

Rural couples have a different problem. For four decades, the working-age generation has formed the backbone of China’s migrant labour force – the men building China’s shiny new cities and the women working in factories, often thousands of miles from home. Unable to settle permanently in the cities they helped to build, they have been obliged to leave their children in the care of grandparents, seeing them only on annual visits home.

But the problem is not only a matter of straitened resources and intolerable life pressures. As Xi Jinping ratchets up the nationalist rhetoric along with calls to give birth for party and country, many of China’s younger generation are in a mood of quiet rebellion. Some are pursuing a form of passive resistance known as “lying flat” – shorthand for declining to work long hours in fiercely competitive environments in pursuit of illusory ambitions. They prefer fewer ambitions and a more relaxed way of life.

Besides, as the Chinese journalist Frankie Huang explained in a 2018 article, young Chinese of her generation have lived all their lives with no siblings and have no attachment to the traditional idea of larger families. Young women like Huang not only fail to see the point of more babies, but they also understand that the personal cost of having them could be high. They would be trading their hard-won independence in the workforce for unrewarded years of childcare.

China’s leaders are finding themselves face to face once more with the nagging question, “will China get old before it gets rich?” That question is a nod to the experience of neighbouring countries, where the demographic dividend was also an important but short-lived factor in economic growth, allowing countries such as Japan and South Korea to attain levels of prosperity that supported their ageing populations. China’s problem today is that although it enjoyed a similar demographic dividend, it has income levels around one-third those of Japan when it was at a similar demographic stage. This makes funding the pensions and healthcare for China’s elderly population a daunting challenge.

It is unlikely to be helped by the other difficulties now visible in the Chinese economy – lower-than-expected growth, the energy price shock, Covid, the slow-motion collapse of property development as an economic driver and the global impact of the war in Ukraine. But even without the fallout from recent events, the imbalance between the working population and the elderly who must be supported has created huge complications.

China is not alone in facing a declining and ageing population: its Asian neighbours and the relatively wealthy countries of Europe all have similar trends, but China suffers from the additional disadvantages of an early retirement age that is politically difficult to adjust, and a longstanding hostility to immigration. In Europe, as in most high-income countries, immigration has long helped to counter the negative effects of population decline.

China’s One Child policy aimed to achieve a fertility rate low enough to halve the size of each successive generation. But as a consequence of pursuing that goal, China’s retired population will be greater than its working population by 2080, and by the turn of the century 100 workers will, between them, have to support 120 pensioners. By that point, China’s pension costs could represent 20% of GDP.

Xi Jinping likes to remind us that the world is changing: in his vision, the US is in decline, and this, therefore, will be China’s century. But now that China is getting old before it has got rich, the dream of prosperity and power that Xi promised his people is faltering. The Chinese economy, for decades an important driver of global growth, is already suffering from a toxic combination of debt, falling productivity and a sinking real estate sector. China’s people have already shown themselves to be in a fractious mood and unafraid to protest. If this is bad news for the global economy, it is even more troubling for China’s leadership.

Isabel Hilton is a writer and broadcaster, and the founder of China Dialogue