This article was first published in April 2022, before the death of Queen Elizabeth II

The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee year was always going to be a gamble for the House of Windsor. On the one hand, it would demonstrate what they do best, a superbly choreographed series of pageants designed to leave audiences around the world agape. On the other, it would highlight just how dependent the whole show has become on one person, the woman whose amazing staying power it celebrates.

Nearing the age of 96, the Queen is 15 years older than Queen Victoria was when she died. When the Jubilee year was being planned, she was still in robust health. Just a month after Prince Philip’s death she went to Westminster to deliver the sovereign’s speech at the opening of parliament. The widow monarch, unlike the forever dolorous Victoria, was as spirited as her lilac wardrobe. She was reasserting her command, and the long-abiding heir was not about to be enthroned.

Nobody could have predicted that the mood of celebration would quickly be overtaken by a series of events that have accelerated the need to question the role and relevance of the monarchy in the 21st century. In fact, the longevity of Elizabeth II’s reign long postponed this reckoning. Having to face up to it now shows the comfort of being able to avoid it for so long.

The most serious of these events was that the Queen’s health suddenly became an issue. And concerns about the mortality of the monarch have inevitably led to questions about the mortality of the monarchy itself. In November, the Queen was driven from Windsor to the King Edward VII hospital in London where she was detained overnight for unexplained “preliminary investigations”. After that, the palace seemed evasive about her condition. And it was nearly five months before she was able to make another public appearance, at Westminster Abbey for a service of thanksgiving for the life of her husband of 73 years, Prince Philip.

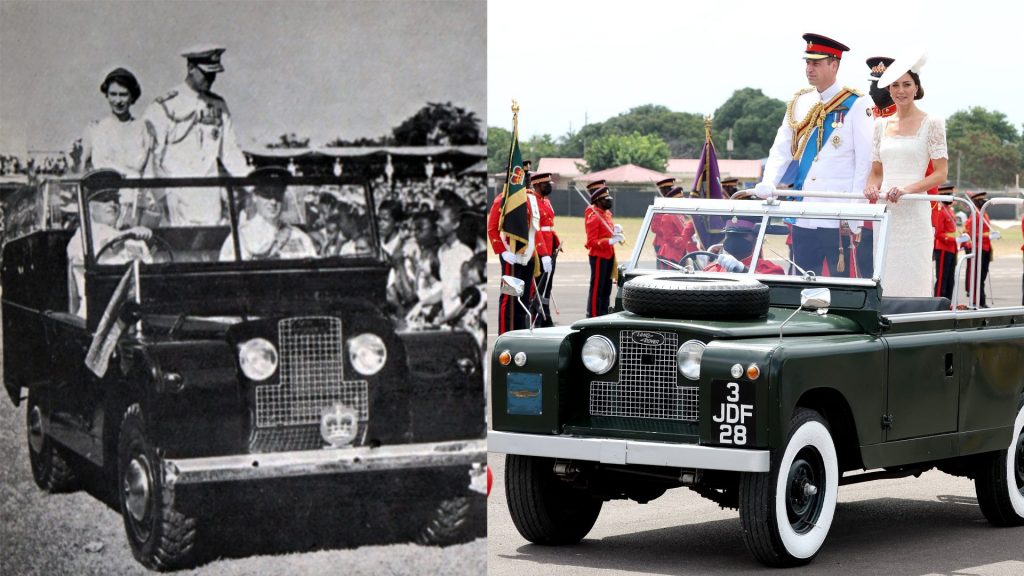

The consequences of that appearance were, to say the least, unfortunate, particularly abroad. After months of banishment from public life, Prince Andrew re-emerged as his mother’s escort, supporting her in and out of the abbey as she walked with the help of a stick. While it was good to know that she was mobile again, the apparent rehabilitation of Andrew sent a message that the Windsor court, if not the Queen herself, did not care that, for most of the world, Andrew’s banishment for his entanglement in the sex-trafficking network of Jeffrey Epstein was well merited and should have been permanent. This, along with the fiasco of a royal tour of the Caribbean by Prince William and Kate just days before that at times resembled a rerun of a 1950s grand imperial progress through the colonies, suggested that the House of Windsor did not understand the peril it faced once the Queen was gone.

What will that absence actually feel like, for the nation? For a start, there will be a kind of visceral reaction in the whole country that is hard to measure, an uprushing of personal feelings about the person, not the institution. For older generations, that will have echoes of the emotions felt when Churchill died. And, in a sense, it will repeat an effect that the novelist VS Pritchett then caught in one sentence: “We were looking at a past utterly unrecoverable.”

But millions of the Queen’s subjects don’t share her past. And we all live in a present that simultaneously weakens the hold of the past while making the future seem no longer within our control. In such a liminal atmosphere the monarchy is dangerously vulnerable because its rituals display such a reverence for the past: uniformed princes with medal-laden chests, courts patrolled by tiers of flunkeys and a string of palaces needing support from the public purse.

In the summer of 1997 the Queen badly misread public sentiment after the death of Princess Diana and, for a while, she was seen as remote and out of touch. There was rumbling about the point of the monarchy, and opinion polls indicated that most people believed it might not exist in another half-century. But, with the help of the Blair spinners and a generous public mood, the Queen recovered her standing. That readiness to forgive is no longer automatic.

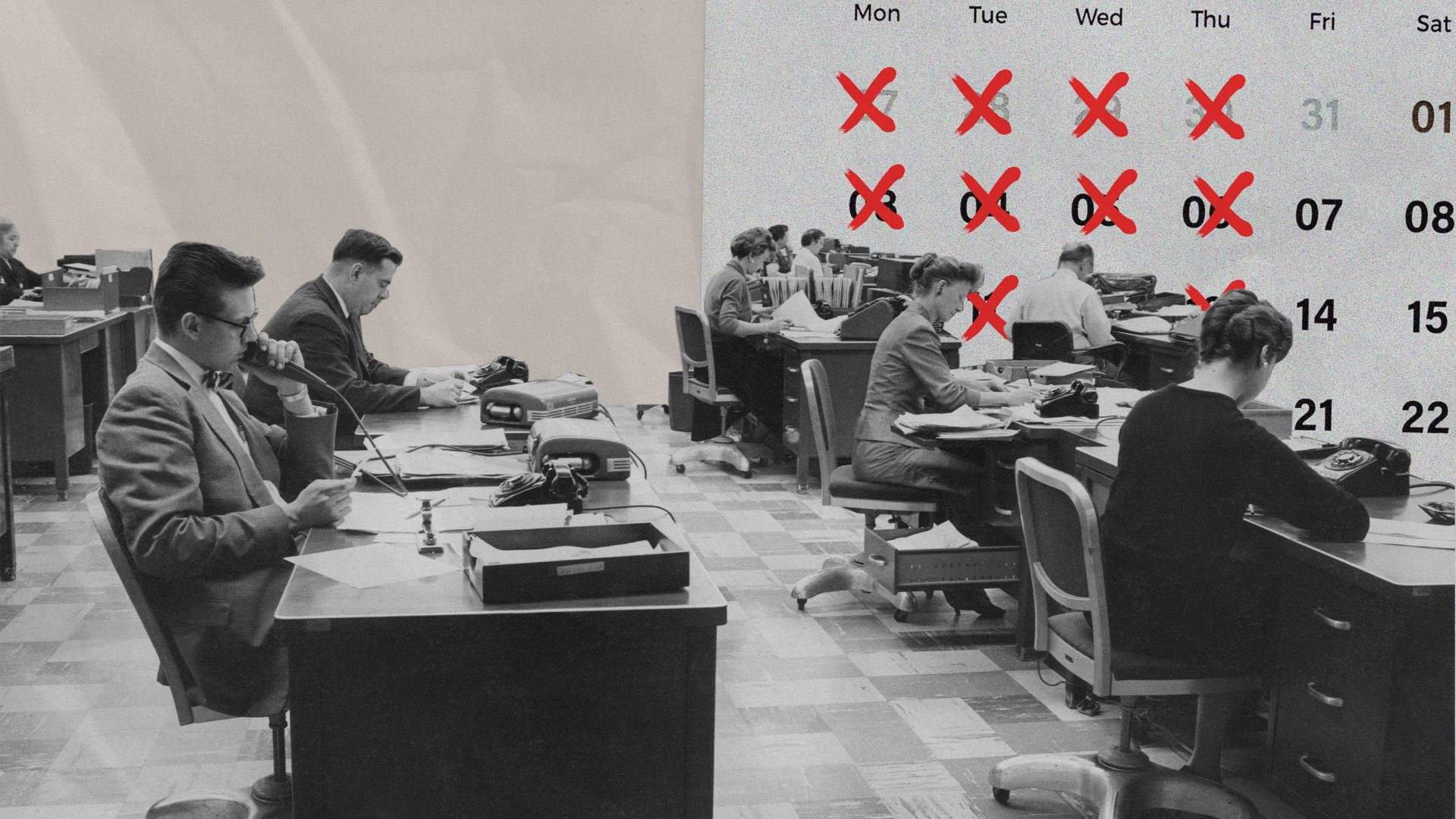

Prince Charles has said that, on accession, he will modernise the monarchy. That is certainly a project he has long rehearsed, but he can’t be specific because it implicitly dismantles things loved and sustained by his mother. Added to that is what he might mean by modernising. He has talked of downsizing. A new generation of children has meant that the immediate family, those in the extended line of succession, now numbers 34. Most of the adults perform royal engagements, but Charles and Princess Anne regularly come out as the hardest working in an annual list prepared by The Times. Any meaningful economies would involve not so much a cull of royal bodies as the kind of root-and-branch trimming of the bloated staffing and hierarchies within the royal household that now look so out of their time.

Whether Charles has the kind of executive grasp to carry out such a task is questionable. The Queen’s move to permanent residence at Windsor Castle has exacerbated the impression that the management of the firm is unravelling. There were already failures of communication and coordination between the Queen’s court, now split between Buckingham Palace and Windsor, and the one established by Charles at Clarence House, which seems to think and behave like a restless new court-in-waiting.

Internecine tensions have gone unchecked since the departure in 2017 of Christopher Geidt, who in 10 years as the Queen’s private secretary was said to have been “the safest pair of hands” she ever had. His rule ended because of complaints to their mother from both Charles and Andrew. Charles wanted to take over more of the Queen’s work than Geidt thought appropriate, and Andrew complained that Geidt was too keen to police his business projects and spending habits.

The continuing loss of grip is apparent from the handling of two crises: the excommunication of Andrew and Scotland Yard’s investigation of the alleged offer of a knighthood for a Saudi billionaire in exchange for a donation to Charles’s personal charity, the Prince’s Trust.

Clarence House said that Charles “had no knowledge of the alleged offer of honours”. There were echoes here of the claim, following Meghan Markle’s complaint about racism and the lack of diversity in the staffing of the royal household, that this had come as a surprise to the family. In this case, the “no knowledge” defence is similarly self-indicting. When a business has your name on it there is a fiduciary duty (if not a moral one) to keep an eye on it. You can’t just slink away into the bushes when it blows up.

If Charles is serious about bringing about significant systemic change to the apparatus of the monarchy, he could start by consolidating the management around one court, not three (the third, the Cambridges’ at Kensington Palace, is a minor player).

There is also the issue of what cast of mind Charles would bring to his own performance as king. There is a strong streak of atavism in his opinions. It often outstrips his knowledge and taste, for example in his sometimes vandalistic campaigns against modern architecture while one of his own pet projects, the Dorset town called Poundbury, is a nostalgic mélange of styles designed to suggest an idyllic England that never existed.

Having trespassed into areas of national policy with his “spider” memos to government ministers, Charles attempted to pull back by saying, as he reached 70 in 2018: “If you become the sovereign, then you play the role as it is expected. So clearly I won’t be able to do the same things I’ve done as heir.” In other words, he won’t air his views, even while still holding them.

In reality, “the role as it is expected” cannot resemble that of his mother because it currently so strongly reflects someone who is as private with her views as he is promiscuous with his. She will leave the throne as personally unknowable as when she ascended to it. That gave her a particular kind of authority that her heir can never acquire. Crucially, it concealed just exactly what degree of agency she actually had within the ill-defined boundaries of a constitutional monarchy.

It’s natural to think of the monarchy as a stand-alone institution, but it isn’t. In 1985, Julian Amery, a Tory patriarch, described it as a “collective monarchy” – meaning that it was part of a shadow power system that included parliament, the courts and the executive. Amery said this arrangement made sure that elected ministers could only shift policy slightly and “then only if that is acceptable to the collective crown”.

The more straightforward effects happen in plain sight. The crown serves as a patronage system by assigning titles and honours, which also propels careers in the executive where gongs go with advancing rank. No other modern democracy indulges in such a method of preferment.

Once this set-up becomes clear, with tentacles sliding into many corners of the nation’s business, it becomes obvious that diminishing or abolishing the monarchy in one clean and bloodless strike wouldn’t be easy. “The collective monarchy” has a mutual interest in the continuity of the crown. One of the most consequential things to understand about Elizabeth II’s reign is that she has had so long in the job that she fully mastered all the levers of this system, covert and public. Unfortunately, this included allowing herself and her family to work in some shady places on behalf of what was perceived as the national interest.

At the heart of this activity is a body few people have ever heard of, the Royal Visits Committee, chaired by a Foreign Office mandarin and including the private secretaries to the Queen, Prince Charles, Prince William and the prime minister. Requests under the Freedom of Information Act for access to its records go nowhere. One reason is that the royal family has frequently been called upon to act as accessories to covert transactions between the UK and Arab monarchies, including arms sales like British Aerospace’s jackpot deal, the Al Yamamah project to supply war planes to Saudi Arabia, which have since been used to obliterate rebels in Yemen.

According to the open source website Declassified UK, members of the royal family have met with Gulf and Saudi monarchs on 217 occasions since 2011. Prince Charles was the most active player, with 95 meetings. At least £1.4m of public money was spent flying royals to Arab monarchies, several of which are notoriously repressive. (Prince Andrew’s activities were of a different order: his career as a grifter was part of his personal cupidity and spread far wider.)

Some collateral damage was done to the Queen herself. Her involvement in horse breeding and racing was long a seductive influence on Arab monarchs with a similar addiction. One of these was Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the autocratic ruler of Dubai, and a power in the United Arab Emirates. At Ascot in 2019 the Queen presented a trophy to Sheikh Mohammed despite rumours, later confirmed in a high court ruling, that he abducted his own daughters to keep them from enjoying the freedoms of a western lifestyle. Once this came out, the palace announced that the Queen would no longer be photographed in public with him.

Successive British governments have shown few scruples in dealing with these regimes in the pursuit of a combination of commercial, security and energy interests. It’s hard not to feel that the Queen accepted that this shady line of work was an obligatory part of her public duties and was carried out in keeping with her own sense of service. Both Charles and William have been schooled in the operations of the shadow world that interlocks national security with commercial interests and the Cabinet Office. Any plan that Charles has to modernise the monarchy would not include severing that connection.

But isn’t a “modern monarchy” an oxymoron? You can’t modernise something depending so much for its authenticity on archaic symbolism without greatly weakening its appeal. The so-called bicycle monarchies of Holland and Scandinavia are neutered to the point of irrelevance. One option would be to “neutron” the show by removing all the royals and leaving the opulence – the palaces, the pageants – as the most potent revenue-raisers of the British tourist industry. But that wouldn’t work because the royal family are themselves the gift that keeps on giving to the global celebrity industry, which is basically writing the daily click-bait narrative that pulls so many visitors to our shores.

Stephen Sedley, a former judge in the court of appeal, wrote in the London Review of Books that: “You could abolish the monarchy and substitute the state for the crown in all our laws and textbooks and (apart from the unappealing prospect of presidential elections) nothing much would change.”

The ticking bomb in that assertion lies in the parenthesis. The talent pool for presidential candidates would inevitably draw from the political class, and that has seldom been in such disrepute. Regular polling shows little appetite for dumping the monarchy – as long as the Queen is there. That could change swiftly when she dies. New polling by statista.com shows that in the youngest age group, aged 18-24, there is already a majority, 41%, for an elected head of state, but the overall score across all age groups is 61% in favour of keeping the monarchy.

The Queen’s own approval rating has held steady at 83%, followed by Prince William with 80%, while Charles remains at 60%. Based on those ratings, hereditary succession looks like the worst option for ensuring the monarchy’s survival. Charles is 73, William 39. By actuarial measure that would mean that William could be 60 before taking over, by which time the firm might be out of business. To look fit for purpose in the 21st century, the monarchy needs a transformative head, not somebody resembling an 18th-century grandee.

In June 2021 Britain enjoyed a central place in the sun at the G7 meeting in Cornwall. For a moment, even Boris Johnson seemed like a statesman.

Britain held the presidency of the group and, as host, designed a display of native assets to meet the occasion. The weather obliged. National leaders stood for the cameras on the sands of Carbis Bay where the surf had calmed to a quiet lullaby. As intended, it conveyed the message that this upscale corner of Cornwall aspired to be as sybaritic as St Tropez.

Without doubt, the star attraction of the show was the Queen who, after all, had been on the world stage since long before many of the other leaders were born. You could sense that some of the other heads of state looked on her with a mixture of respect and bemusement: what kind of country was still comfortable pledging allegiance to an anachronism? But then, as she stepped carefully up to a platform to take centre place in a group photograph, she said audibly: “Are you supposed to look as though you are enjoying yourself?”

She clearly was. They were all ephemeral. In contrast she was, as far as anyone could ever become, a truly enduring national institution. Of the many duties of her day job, the one she had always liked best was this one, mingling as an equal with the top office holders of the world. After Cornwall, the Queen invited US President Joe Biden and the First Lady to tea at Windsor Castle. Biden is more mindful of Irish history than of England’s and was angered by Johnson’s cavalier handling of the Northern Ireland border issue. But the chat over the teacups went off well as a reaffirmation of the Atlantic partnership after the ruptures of Trump.

This served as a reminder of the part played by the monarch in deploying Britain’s soft power. As she matured in her role, Elizabeth II morphed into something beyond the figurehead of her realm. She embodied an idea of post-imperial Britain as a globe-girdling force for good. It was no accident that the royal yacht was named Britannia, the sexless feudal heroine of the island people. With the Queen aboard she was worth more as a symbol than a whole naval battle group.

Throughout her reign, the Queen has seen 14 prime ministers grapple with the problem of national decline, and rarely well. The state and the crown were locked in a struggle pitting emotional attachment to an idea of national stature and identity against ineluctable tides of geopolitical change. Sometimes it came out well. As the empire dissolved into the commonwealth the Queen’s soft power was used to decisive effect, never more boldly than in 1957, when Harold Macmillan asked her to intervene in Ghana, where Kwame Nkrumah, the first prime minister of the newly independent state, was flirting with Soviet Russia. Driving through Accra, the capital, in an open car with Nkrumah (at some risk) and then dancing with him at a state ball won him over to the west.

The same spell worked in Europe. In 1972, with Britain finally joining the Common Market after years of obstruction by the French, the Queen was sent on a state visit to Paris to woo President Georges Pompidou. Once more a motorcade drew crowds who welcomed a display of regal glamour that the republic could not provide and a new spirit of Anglo-French amity prevailed.

Perhaps the Queen’s most heartfelt coup, though, came at Dublin Castle in 2011, when in the first visit by a monarch to Ireland in a century, she was sent to follow up the Good Friday Agreement with a gesture of reconciliation after so much mutual bloodletting. In a speech at a state dinner in the castle she apologised “for things which we would wish had been done differently or not at all”. She got a standing ovation and the Irish Times called her “a remarkable woman in her own right”.

But, as it turned out, the G7 meeting was probably the last time the Queen will be engaged at that level with other heads of state. That work is over for her now, and that world is passing. The age group in which 81% support the monarchy, 65-plus, identifies so closely with her and her values that they tend to see the whole of her reign as a kind of golden age that cannot be repeated. That’s clearly allowing nostalgia to overcome reality – among that cohort are the sentiments that fuelled Ukip and Brexit, although the Queen has never indicated, by code or action, that she believed in Little England and she surely opposes any break-up of the union. Yet the resurgence of the Scottish and Welsh independence movements increases the sense that, golden age or not, the past is another country.

Since the G7, the change in her energy has been obvious, leaving it uncertain how far she will be able to personally join in this summer’s headline ceremonials. Street parties – forever recalling the jubilance of VE Day in 1945 – will be offering plates of Jubilee Pudding, according to a recipe chosen by the palace as the winner of a national contest, suggesting a royal view that, for them, The Great British Bake Off is a cultural benchmark.

The greatest of the unresolved issues about the monarchy’s future is about the way and when the succession will happen. The Queen has always said she will remain on the throne as long as she is able. That remains a decision only she can make. If she should decide to step down and make way for King Charles III and Queen Camilla, the heir will certainly believe he is ready.

Britannia was decommissioned in 1997. This great emblem of soft power at its most opulent steamed into history from Hong Kong, where Charles had watched the handing over of the colony to China. His sense of history was shaped more by his own discomfort, flying there in business class on British Airways was, he noted, “so uncomfortable… such is the end of empire”. He went home in more familiar comforts, aboard the royal yacht. Britannia is now permanently berthed at Leith, Edinburgh, and serves as a very popular tourist attraction and as a museum of glories long gone.

Clive Irving was a founding editor of Condé Nast Traveller, where he is still editor emeritus, and is a regular columnist for the Daily Beast. His book The Last Queen is published by Biteback, £9.99 paperback.