Just before midnight on December 15, 1969 a man fell to his death from a fourth-floor window at Milan’s central police station. Three days earlier, a bomb had exploded at the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura on the city’s Piazza Fontana and killed 17 people.

Several known anarchists had been rounded up for questioning, one of whom, 41-year-old railway worker Giuseppe “Pino” Pinelli, ended up dead in circumstances never satisfactorily explained. The bombing had been carried out by far-right terrorists. Pinelli was completely innocent.

The Pinelli scandal seems unlikely source material for a madcap farce by one of Europe’s greatest modern comic playwrights, but in Accidental Death of an Anarchist, Dario Fo created a remarkably astute piece of work that’s still performed around the world today.

While most modern audiences have probably never heard of Pinelli, the play’s enduring success lies partly in it being simply an outstanding piece of theatre, but also in how its themes and structure make it easily adaptable for contemporary audiences.

Accidental Death enjoyed a well-received run in London’s West End this year, with every performance ending with the statement: “Since 1990 there have been 1,862 deaths in police custody or following contact with police in England and Wales” projected on to the back wall of the stage.

Adaptability has been at the heart of the play since the start: Fo wrote and staged the original so soon after Pinelli’s death that he found himself updating the script sometimes nightly as more information emerged.

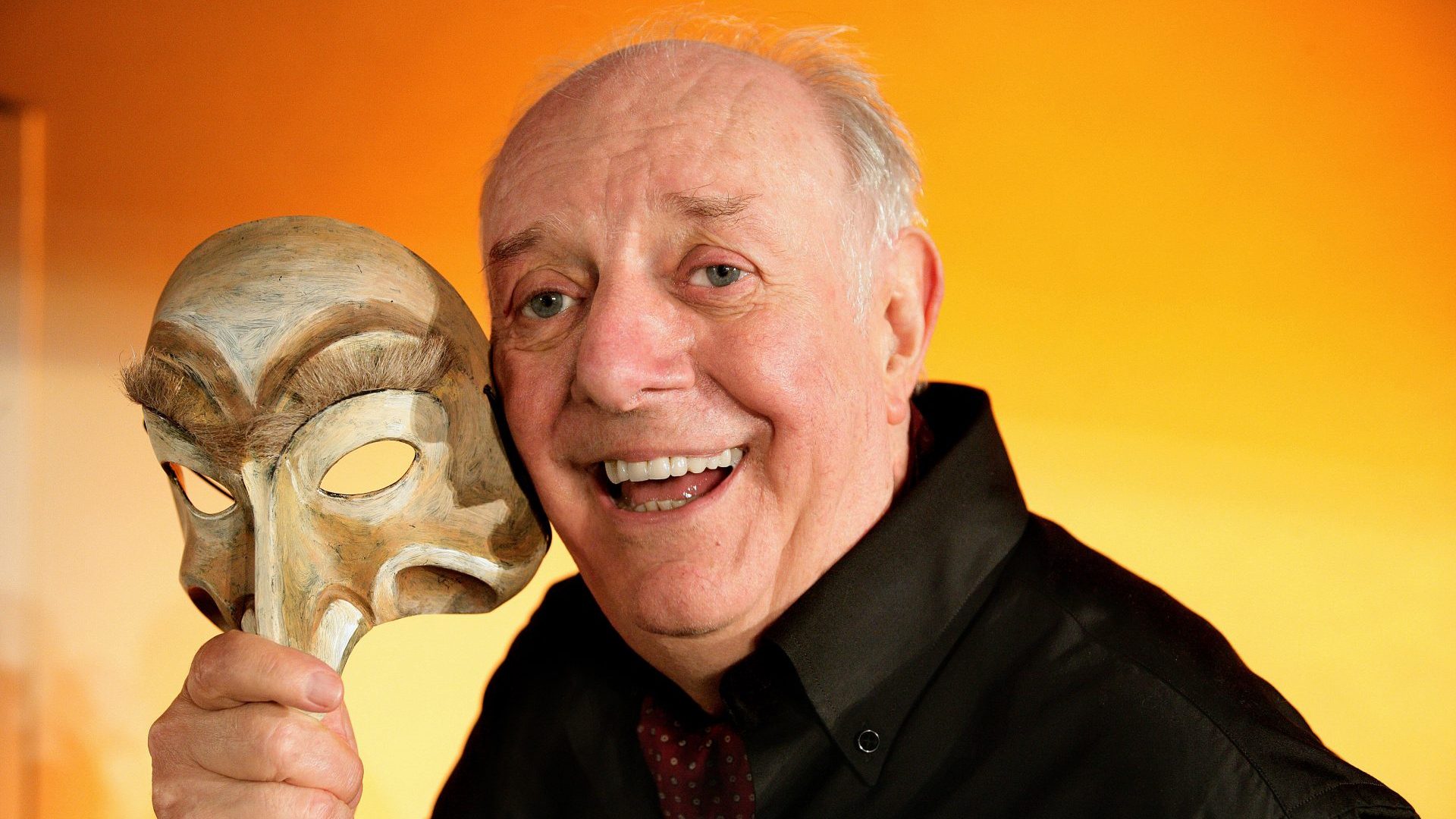

Few cultural figures can have combined political activism and theatre as successfully as Fo. The author of more than 80 plays, many written with his wife and creative partner, Franca Rame, as well as an actor, clown and author, who published his first novel at the age of 88, Fo’s talents have often been overshadowed by the controversial nature of his work, which was just how he liked it. After all, if he wasn’t upsetting the right people, he wasn’t doing his job properly.

Fo’s one-man show Mistero Buffo, for example, was first staged in 1969 and proved so successful in its provocation that, following a 1977 television broadcast, the Vatican itself denounced it as “the most blasphemous show in the history of television”.

Such establishment nose-tweaking was Fo’s forte and prompted countless attempts at retribution. He clocked up more than 50 police prosecutions during his career, for example, a record that only seemed to earn him more admirers. Fo was beaten and arrested during a performance of Mistero Buffo in Sardinia during the 1970s, only for the audience to follow him to the police station for a noisy and ultimately successful protest.

“The whole audience turned up in front of the prison,” Fo told the British theatre critic Michael Billington. “They sang, shouted and protested the whole night through and what started out as an act of police repression ended up as a popular defiance of authority.”

In 1997 he became an unlikely recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, an award that had the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano huffing that “giving the prize to someone who is the author of questionable works is beyond imagination”. Fo learned of his award in characteristically idiosyncratic fashion – driving north from Rome to his home in Milan after a show, a car drew level with him on the highway in which a passenger held up a sign reading: “Dario, you have won the Nobel Prize”.

“We have had to endure abuse, assaults by the police, insults from the right-thinking and violence,” he said in his Nobel acceptance speech to the Academy. “Yours is an act of courage that borders on provocation.”

The road to the Nobel Prize had begun in the small town in Lombardy where Fo was born to a railway stationmaster father who was also a keen amateur actor, and a mother who would go on to write a well-received memoir of her peasant background called Il Paese delle Rane (The Country of Frogs).

Much of Fo’s childhood was spent accompanying his grandfather through the surrounding countryside selling vegetables, watching how the old man expertly drew a crowd by telling fantastical stories mixed with items of news picked up on the road. This combination of performance and the accumulation of working-class stories and experiences forged in Fo an awareness of the chronic social injustice that would underpin his life’s work.

“I lived side by side with the sons of glassblowers, fishermen and smugglers,” he recalled. “The stories they told were sharp satires about the hypocrisy of authority and the middle classes, the two-facedness of teachers and lawyers and politicians. I was born politicised.”

The glassblowers in particular proved to be a key influence.

“These were old storytellers who taught me the craftsmanship, the art, of spinning fantastic yarns,” he related in his Nobel speech. “We would listen to them, bursting with laughter that would stick in our throats as the tragic allusion that surmounted each sarcasm would dawn on us.”

He might not have realised it at the time, but Fo was placing himself among ancient performing traditions harking back to medieval jesters and fools who spoke hard truths beneath the clowning. It was also an echo of the commedia dell’arte tradition of Italian theatre.

He had joined the army at the outbreak of the second world war, but soon deserted, returning home to be hidden by parents who were also busy helping Jews and escaped British PoWs to get into Switzerland. After the conflict he became captivated by the piccolo teatri movement, which staged improvised monologues satirising current affairs, which inspired a move to Milan and a theatre company where in 1951 he met Rame. Marrying in 1954, the couple went on to create some of the most innovative and provocative theatre ever staged in Europe.

Fo’s targets ranged from the carabinieri to the influential Fiat Agnelli family – the subject of his 1981 play Trumpets and Raspberries – to Silvio Berlusconi and Vladimir Putin. His work might have cost him bans from television, long hours in police cells and occasional physical injury, but to the end of his life he regretted nothing.

“At the root of everything I write is tragedy,” he said. “One must never forget that Accidental Death involves a man who has been thrown out of a window and Trumpets and Raspberries shows that terrorism is the inevitable byproduct of a society where the police, the judiciary and political institutions are all riddled with graft and corruption.

“You must always be aware of this reality. The laughter is simply a means of making the audience confront the problem.”