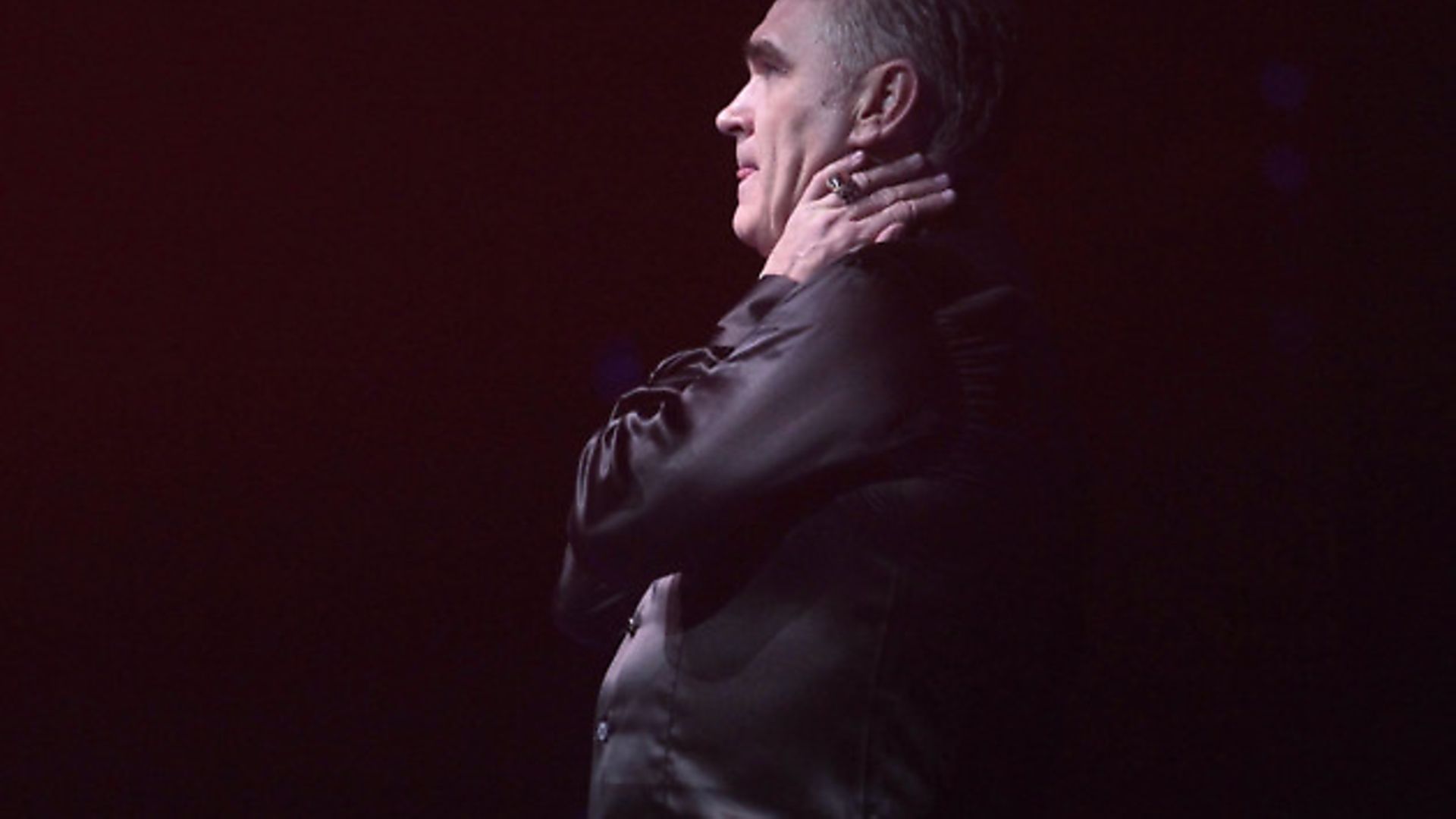

Aged 13 and newly converted to vegetarianism, the discovery of The Smiths’ album Meat is Murder was genuinely revelatory for me. It kickstarted a nearly 10-year-long obsession with Morrissey, the band’s charismatic and pugnacious lead singer – an obsession that carried on well into my early-20s.

Until last year I continued to travel up and down the country – and sometimes abroad – to see gigs and meet up with friends I’d met queuing for the front row or talking about Morrissey with online. I met one of my best friends several years ago via an annual ‘Morrissey meet-up’, and last year we went to Barcelona ostensibly for a holiday but actually to attend a gig in a tiny Spanish nightclub, queueing for hours in the sun to get near the front. I found solace, comfort and community in the spirited spite of Moz’s eloquent lyrics, and even got a few of them incorporated into tattoos.

So, as a proud Remain voter, it’s more than a little disheartening to hear Morrissey’s latest comments on Brexit.

‘It’s been shocking to witness the refusal of the UK news media to be fair enough to accept the final decision of the people, simply because the decision does not suit the establishment,’ he told Israeli website Walla. ‘The BBC persistently smear people who voted leave, condemning such people as being irresponsible, drunken racists.’

I’d actually love to say that it feels like a betrayal, but it’s just one more unsurprising addition to a long line of reactionary, poorly thought through statements from the singer. In recent weeks alone, Morrissey has claimed that the media hate George Galloway and Nigel Farage, who he bafflingly describes as ‘liberal educators’, because they ‘respect equal freedom for all people’, and criticised London mayor Sadiq Khan for eating ‘halal-butchered beings’.

Vegetarianism is great, and animal rights are obviously a noble cause, but bringing Khan’s Muslim faith to the fore sounds an awful lot like racism, making it a little rich for Morrissey to describe the (alleged) ‘condemnation’ of Leave voters as ‘irresponsible racists’.

In 2007, he said he felt like England had been ‘thrown away’, and complained that ‘if you walk through Knightsbridge on any bland day of the week, you won’t hear an English accent… You’ll hear every accent under the sun apart from the British accent.’

In 2013 Moz stated that he had ‘nearly voted for UKIP’, and he’s previously referred to Chinese people as a ‘subspecies’ because of their treatment of animals – hardly the best person to judge whether someone is being falsely accused of racism. It’s a very long way from his 1990 declaration that ‘there are some bad people on the right’.

In any case, though many of those who voted Leave aren’t racist, what pro-Brexiters have done is stand alongside campaigners who certainly are, and there’s the question of whether a vote for Leave was also an implicit legitimation of that racism. Since the EU referendum, hundreds of incidents of hate crimes have been reported, with many perpetrators telling victims to ‘go back to your own country’. It’s not hard to see a link between this Us vs Them mentality and the result of the referendum, with freshly emerging racist narratives vindicating the views of many who had previously kept their opinions silent and who now feel empowered to air them publicly – and sometimes violently. The murder of Jo Cox, which came at the height of the Brexit debate, should also have served as a stark reminder of what was at stake when we decided whether to stay in the European Union; a staunch campaigner for the rights of refugees, immigrants and other minorities, Cox represented the multicultural values that genuinely do make Britain great.

This beautifully diverse and multicultural Britain is not the one present in Morrissey’s work, though; throughout his career, he’s wistfully depicted the country as a proud but fading island, adrift without identity. The Queen is Dead more or less screamed ‘there is something rotten in the state of Salford’, and later songs like Everyday Is Like Sunday and Come Back to Camden painted yearning portraits of an England that had long disappeared – and probably never existed to begin with. At heart, Morrissey’s idea of what ‘Britain’ means is entirely romanticised and closer to fairytale than reality. It would be unobjectionable if such views didn’t have an impact on the lives of so many people.

Morrissey’s anti-Brexit stance is also personally hypocritical; his parents were Irish immigrants to Manchester, and he himself has lived all over the world, including recent stints in Italy. Such freedom of movement will probably still be available to him after Brexit, simply because he’s famous and fairly wealthy; to deny that to others, especially those who don’t have the same material and political privileges as him, is shortsighted at best and deeply selfish at worst.

I still find his position baffling – one of the reasons people love Morrissey so much is because his lyrics speak so directly to those who feel as if they are outsiders, and his large gay and Mexican fan bases show how powerful that draw is. Indeed, his song Mexico criticises racism in America; ‘if you’re rich and you’re white you’ll be alright’. It’s a sentiment at odds with his support of UKIP, who are often considered to be exclusionary and racist, and highlights the inherent contradiction in many arguments for Brexit.

Although Nigel Farage, who Morrissey says he ‘likes a great deal’, might like to see himself as a political black sheep, he’s a millionaire public school-educated ex-banker – not an outsider in any real sense.

It’s a stark comparison to those who really are oppressed and who really are outsiders – the migrants and refugees that Brexit will most severely impact – who Morrissey seems completely unable to defend because of his desperation to cling onto an idealised version of England. Whether Morrissey’s criticism of the BBC’s coverage of Brexit is to do with his adolescent fixation on insulting authority figures or whether it really is about politics, he’s only adding to a damaging narrative that alienates those in our society who most need to be supported.

Will I always love Morrissey’s music? Of course. But when it comes to politics, he’d be best taking his own advice… Get Off The Stage.

Emily Reynolds is a freelance writer for Vice, New York magazine and The Guardian, among others. Her book A Beginner’s Guide To Losing Your Mind is out next year.